Much of downtown Brooklyn, which for my purposes includes Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Vinegar Hill, Red Hook and part of Fort Greene, no longer exists. It used to be home to a collection of streets wide and narrow, full of tenements, stores, and cobblestones, many overshadowed by dark forbidding elevated structures where trains rattled on their way to and across the Brooklyn Bridge (yes–the Brooklyn Bridge: els used to traverse it).

Many of these streets are now gone, many of them eliminated because of Robert Moses’ Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, many more removed for parkland and urban renewal and yet more for government buildings. Few remember these streets by now.

Fulton Street? The grande dame of Brooklyn streets…third longest in the borough, surpassed only by Flatbush and Bedford Avenues…first and foremost in the Brooklyn Street Necrology?

Of course. A mile-long section of Fulton Street, known as such since 1814 in honor of steamboat and submarine pioneer Robert Fulton, one of Brooklyn’s most ancient roads, no longer exists or has been renamed!

These days, Fulton Street runs a rough east-west route from Adams and Joralemon Street on the west to Eldert Lane on the Queens border, where it undergoes a name change to 91st Avenue.

This remnant of old Fulton Street runs diagonally from Joralemon Street northwest to Brooklyn Borough Hall. It is now a pedestrian mall.

Prior to 1950, Fulton Street snaked southeast from the old Fulton Ferry landing (a ferry joined Manhattan’s and Brooklyn’s Fulton Streets until 1924) and wound through a Brooklyn Heights much different from today’s. In fact, the change that came to Fulton Street is emblematic of the changes that were made to this part of Brooklyn between 1950 to 1960. An entire neighborhood was wiped out and made unrecognizable.

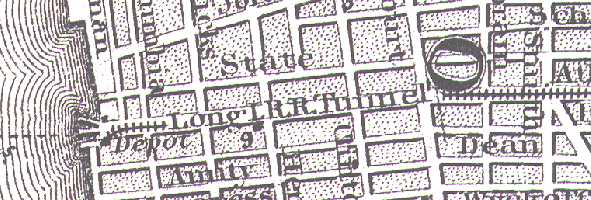

In this scan of an 1827 map of Brooklyn (this pretty much was all of Brooklyn at that time) Fulton Street, center, snakes southeast, southwest and then southeast again.

As a look at any picture book of old Brooklyn indicates (such as Dover’s Old Brooklyn In Early Photographs 1845-1929), Fulton Street in this era was the dominant street of the borough, and featured such edifices as the Mechanics Municipal Hall, the Arbuckle Building (formerly Dieter’s Hotel, where turtle soup was the renowned delicacy), the Park Theater, and the Kings County Elevated Railroad (later a part of the BMT), which covered Fulton Street from the ferry landing all the way to East New York from 1887 to the early 1940s. Brooklyn Borough Hall (formerly Brooklyn City Hall until consolidation with New York City in 1898), Gage and Tollner’s Restaurant at Fulton and Smith Streets, and the Dime Savings Bank at Fulton and DeKalb Avenues, are reminders of the pre-1950 days.

Department stores like A&S, Loesers and Namms, and theatres like the Brooklyn Paramount, the Loew’s Metropolitan, the Fox, The Orpheum and the Albee (which I remember for its white type on black marquee) are gone too…though some of the old Paramount, including its giant 1928 Wurlitzer pipe organ, have been preserved at the Long Island University’s basketball court.

Even now, a stroll along the garish Fulton Mall (from Adams Street east to Flatbush Avenue) and a skyward glance reveals ancient flourishes and even patches of old advertising that go back to the early days of the 20th Century and even earlier.

Downtown Brooklyn’s aspect utterly changed, and Fulton Street lost much of its old personality, when entire blocks just east of it were razed between 1950 and 1960 to make way for Samuel Parkes Cadman Plaza, which served to add a lot of green to downtown Brooklyn, which was needed. (The el had already come down in the early 1940s).

Samuel Parkes Cadman (1864-1936) was a Methodist minister and leader of the Central Congregational Church in Brooklyn from 1901 till his death. It was Rev. Cadman who called the then-new Woolworth Building in Manhattan the “Cathedral of Commerce.”

The plaza provides views of the Manhattan Bridge from the steps of Borough Hall and allows the beautiful US Post Office Building on Tillary Street to be seen much better than it had been before the blocks were cleared out.

Perhaps inspired by Cadman Plaza, Boston scuttled its old seedy Scollay Square in favor of the rather sterile Government Center in the early 1960s.

The construction of Cadman Plaza caused Fulton Street to be renamed as Cadman Plaza West from the ferry landing to Court and Montague Streets. Washington Street, on the eastern end, was renamed Cadman Plaza East.

Renaming Fulton Street as Cadman Plaza West from the old ferry landing (seen at right) southeast to the Brooklyn-Queens expressway made no sense whatsoever, because Cadman Plaza extends from Borough Hall only as far north as the BQE.

NYC recognized this anomaly in the late 1970s and re-renamed that section of Fulton Street as Old Fulton Street.

Fulton Street, however, is just one of dozens of streets of Downtown Brooklyn that have disappeared, as we shall see…

BROOKLYN HEIGHTS

Brooklyn Heights was Manhattan’s first suburb. A ferry was first established from the end of what is now Fulton Street in 1814. Fulton Street, at that time, was the main road that connected Brooklyn to the rest of Long Island: it ultimately connected with what is now Jamaica Avenue and remained a toll road until well into the 19th Century. Maps first appeared that subdivided holdings of landowners named Pierrepont, Joralemon, Middagh, and streets named for them are still there today.

Brooklyn Heights’ street layout remains much as it was when it was first surveyed, although there are a few exceptions…

When Atlantic Avenue was first mapped in the early 1820s, it was known as District Street and ran along the southern boundary of the village. By at least 1845, though, the street was known as Atlantic Avenue.

The 1847 Williams map shown above is the only map I’ve seen that shows the long-abandoned Long Island Rail Road tunnel that was in service between 1842 to 1859 between Court Street and the waterfront under Atlantic Avenue. Although no less a Brooklyn chronicler than Walt Whitman mentions the tunnelin several articles, after the tunnel was closed in 1859 it remained largely forgotten for many decades until railroad and trolley historian Robert Diamond discovered a passageway to it.

The railroad ended at the East River waterfront. There was a frame depot built at the terminal in 1836; it was torn down in 1914. The railroad, originally at grade, was placed in the tunnel in 1842 as Atlantic Avenue became a prominent shopping street. Today it is lined with antique shops and Middle Eastern restaurants. Over the years Atlantic Avenue was expanded eastward, with the LIRR operating first at grade, then elevated and placed in a tunnel along its length. Atlantic Avenue now extends to the Van Wyck Expressway in Jamaica, where it becomes 94th Avenue.

District Street, which ran along the southern edge of Brooklyn Village, from the waterfront east to Red Hook Lane, is now called Atlantic Avenue.

Other lost streets in Brooklyn Heights…

Location: from Clinton Street west to the East River, a block south of Pierrepont Street

What’s there now? Montague Street. Originally named for the family of local landowner Hezekiah Pierrepont’s wife, the name was changed to Montague in honor of Lady Mary Montague, a British author and member of the Pierrepont family.

The name change occurred by at least 1850.

Montague Street used to descend to the East River via a picturesque stone arch. The arch, and the nearby Penny Bridge which connected Montague Terrace and Pierrepont Place over the descending Montague Street, were demolished in 1946 to make way for the BQE.

Location: between Fulton Street and Court (Moser) Street, south of Pierrepont Street

What’s there now? Montague Street.

Constable Street to the west, and Evelyn Street, to the east, were joined about 1850, and at that time the new combined street was renamed Montague Street.

Today Montague Street is the main shopping street in Brooklyn Heights.

Location: from Pierrepont Street at about Fulton Street southwest beyond Atlantic Avenue

What’s there now? Court Street. Moser Street was originally named for Joseph Moser, a prominent political figure in Brooklyn Village in the 1820s.

While it doesn’t follow Moser Street’s exact path, Court Street, likely renamed in recognition of local law offices near Brooklyn’s then-City Hall, had appeared by the 1840s and absorbed Moser Street’s path.

Location: from Joralemon Street west of Clinton Street southwest to State Street

What’s there now? Sidney Place. Probably named in honor of James Monroe, 5th President of the USA, but the name was changed in the 1830s to commemorate Sir Philip Sidney, the 16th-Century British statesman/author.

While Brooklyn Heights lost one Monroe, it gained another, as a Monroe Place would soon appear a few blocks to the north, after Monroe Street’s name was changed.

Location: From Atlantic Avenue south to Amity Street between Hicks and Columbia Streets

What’s there now? The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Original BQE sign (since torn down) at site near where Emmett Street used to be

In the early 1950s Brooklyn Heights was embroiled in controversy as Robert Moses wanted to bisect the community with the proposed 6-lane BQE. Community opposition forced him to run the BQE along the waterfront, creating the Promenade (known on maps as the Esplanade) providing beautiful views of lower Manhattan.

The curve in the BQE towards the waterfront eliminated Emmett Street, plus the section of Columbia Place between Atlantic Avenue and State Street.

Location: Both West Jackson and Waring Street appear on 1820s-era maps between Clinton and Hicks Streets north of Pierrepont Street.

What’s there now? It’s possible that these streets were there on maps only. Certainly by the 1840s, Love Lane had appeared in this site; Love Lane had been an Indian trail leading to the East River.

Location: Shown on maps from the mid-1820s, Buckbees Alley ran between Fulton Street at (former) Market Street and Poplar Street.

What’s there now? The Brooklyn Children’s Aid Society Orphanagewas constructed on the site in 1883. It survives as apartments. “Built as a hone for indigent newsboys”--AIA Guide

COBBLE HILL/RED HOOK

Although they are neighboring neighborhoods, no two ‘hoods could possibly be more different from one another than these two. Gentrified and genteel Cobble Hill contains row after row of well-kept brownstones, mom and pop shops on Court and Smith Streets, and a small-town feel, while just across the BQE, Red Hook is gritty and urban, with projects and factories. Both neighborhoods have awesome views of Manhattan that, astonishingly, are exploited very sparingly.

The street patterns of these neighborhoods are pretty much as they were when first settled in the early 1800s. There have been a few surprising street name changes. The most change to occur in the pattern came between 1950 and 1954 when the Brooklyn Queens expressway was rammed through.

Location: from Court Street between Butler and Baltic Streets west to the waterfront

What’s there now? Kane Street. The name change occurred sometime after 1916. Old concrete sign at Cheever Place still says Harrison Street

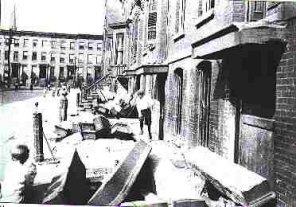

Location: from Rapelye Street west of Henry Street southwest to Coles Street. 1920s view of the doomed Manhasset Place.

What’s there now? The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Surprisingly, along with Emmett Street (see above), Manhasset Place was the only street eliminated when then BQE was constructed here in the late 40s and early 50s.

Earlier, the Brooklyn- Battery Tunnel had also been constructed here. Rapelye and Coles Streets were also dramatically curtailed by all the new routes.

Why a short Brooklyn thoroughfare should have the same name as a North Shore Long Island town(now a tony enclave featuring the Miracle Mile) should remain a mystery since Manhasset Place is long gone. Manhasset was also the name of a Native American tribe inhabiting Shelter Island between the Long Island forks.

Location: between Hicks and Henry Streets on President Street.

What’s there now? The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Location: from Smith and 9th Streets west to Columbia Street

What’s there now? West 9th Street.

The name change had been made by 1898. The question is why? Although Brooklyn already had a Church Avenue and a Church Lane, it didn’t have a Church Street. At the same time, there alreadywas a West 9th Street in Brooklyn, in Gravesend. Likely, the change was made before Gravesend became a part of Brooklyn.

Smith and 9th Street is the site of Brooklyn’s highest subway station, serving the IND Crosstown and 6th Avenue lines (F, G)

Location: Dwight Street northwest to Van Brunt Street south of Verona Street

What’s there now? Visitation Place.

One half of Tremont Street was lost when the 12th Ward Park was expanded and renamed Red Hook Park, and the street was renamed for the Visitation of Our Lady R.C. Church.

Location: from Otsego and Bay Streets northwest to Buttermilk Channel

What’s there now? Coffey Street.

A lone remnant of Partition Street can still be found in this concrete sign on a building on the NW corner of Coffey and Conover Streets.

Photo: Jeff Saltzman

The change was made prior to 1898.

Fulton Street in Manhattan was also called Partition Street until the 1820s.

Location: from Richards Street (originally from Dwight Street) northwest to Conover Street and Commercial Wharf

What’s there now? Pioneer Street.

The change was made prior to 1898.

Location: from Otsego and Halleck Streets northwest to Conover Street.

What’s there now? Beard Street.

The change was made prior to 1898.

In addition, large chunks of Mill Street, Centre Street and Bush Street were eliminated by the forbidding Red Hook Housing project in the 1930s.