Unnoticed in the gold-plated greenbacked canyons in the shadow of Wall Street is a short, one-block, curved street called Stone. Remarkably immune to Lower Manhattan’s incredible cycle of renewal in the 20th Century, little Stone Street, which stretches between Coenties Alley and Hanover Square, looks remarkably like it did in the late 19th Century. It’s as if it was completely oblivious to change.

Recently, however, Stone Street has been noticed. It’s the object of an urban renewal project designed to intensify its 18th-Century look. Will the project come off as authentic or wind up looking like a theme park? Your webmaster’s bet’s on the latter, but you never know.

First, some history. According to NYC historian Hope Cooke (who between 1963 and 1975 was the Queen of Sikkim), author of Seeing New York:

From early settlement, elite Dutch families, including brewers, lived on winding Stone Street, then segmented into ‘Brouwers” or Brewer’s Street to the south of Coenties Alley and “Hoogh” or High Street to the north.

(The section of Stone Street between Broad Street and Coenties Alley was obliterated by the construction of 85 Broad Street in 1983. But the curved elevator lobby mimics Stone Street’s old path.) Another section of Stone Street runs between Whitehall and Broad Streets.

Stone Street got its name in 1656. It was something of a boast, as it was the town’s first road to get paving. (The Belgian blocks on Stone Street now are new construction.)

Between 1691 and 1797 Stone Street was called Duke Street; after the Revolution, most of New York’s street names recalling royalty had their names changed.

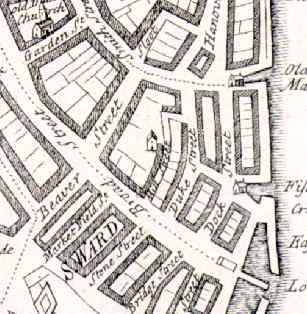

This is a 1740 map of Lower Manhattan by John Carwitham. Note Stone (Duke) Street near the center. It follows the same path today.

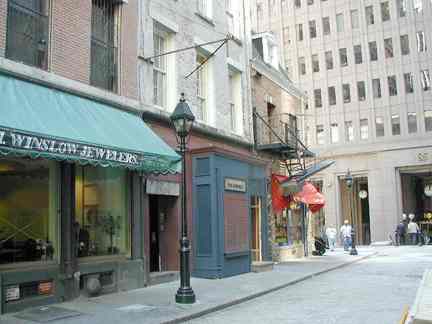

Many of the buildings on Stone Street date to 1836, when Lower Manhattan was rebuilt following adevastating fire in 1835. No building on this part of Stone was built later than 1929.

At 57 Stone Street is a 1909 building with a front-end gable, faced with yellow glazed bricks. It is a playful nod to 17th-century styles when wealthy Dutch merchants tried as best they could to replicate the houses they lived in back in Holland. Gabled houses were a signal of wealth in New Amsterdam.

A 2001 movie shoot found Stone Street attired in 19th-Century raiment:

One of Boston’s longstanding principle squares and transit hubs is Haymarket. 18th-century New York never had a specific street or square called Haymarket, but it indeed had a hay market, the Oswego Market, on Broadway between Cedar and Liberty Streets until 1811.

Far from a longstanding establishment, Winslow Jewelers is a a new addition to the retrofitted Stone Street.

Only on Stone Street can the 1919 Chubb & Sons Building (#54) be considered a modern intrusion! In 1919, though, attention to detail was still a big part of architecture; notice the fancy entablature with the building number.

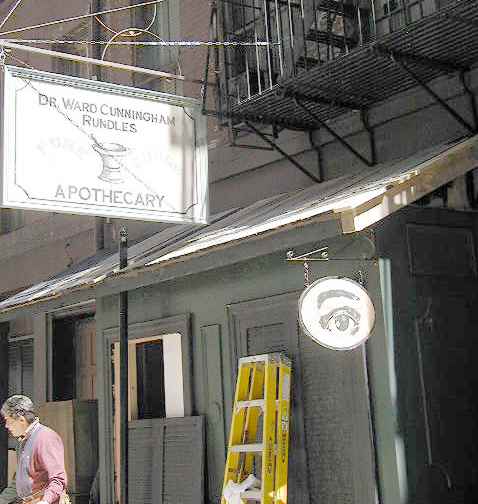

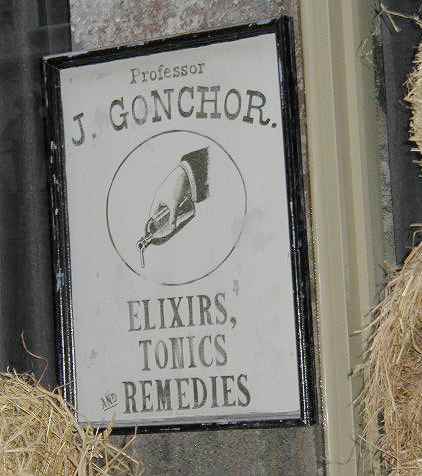

An ‘apothecary’ is an old word for a pharmacy; as Danny Kaye would say, a ‘vessel with a pestle’ is an old symbol for a drugstore.

Snake-oil type potables were widespread in the 1800s, before people knew better. At least I think it was the 1800s. I gotta take more ginkoba.

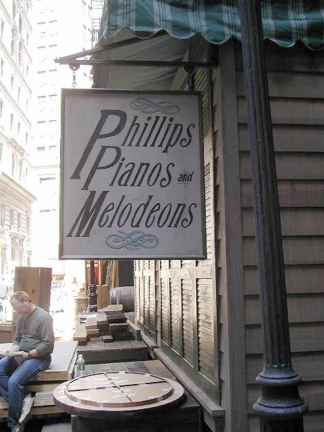

A melodeon is a small organ.

A plywood wall was erected on Hanover Square facing Stone Street for a recent movie production.

Workers restore Stone Street to 19th Century grandeur.

Sources

Seeing New York, Hope Cooke, 1995 Temple University Press

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

New York: A Guide To The Metropolis, Gerard Wolfe, 1975 McGraw-Hill, updated 2000

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Manhattan In Maps, Robert Auustin and Paul Cohen, 1997 Rizzoli

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

As You Pass By, Kenneth Dunshee, Hastings House, 1952

Out of print

E me at erpietri@earthlink.net or kevin@forgotten-ny.com.

5/9/01