Though the hot sweltering Sunday, June 27, 2010 weather kept a number of tourgoers away (by apparent contract with the Almighty, ForgottenTours are never held in sunny, brisk, cool weather) 30 diehards still made it to Bushwick, Brooklyn for the 41st tour in a sequence that began June 1st, 1999 — on a nearby thoroughfare, Brooklyn’s Broadway. This time, the tour was just one avenue away, on Bushwick Avenue, in which the mansions, churches and workplaces built by beer barons of over a century ago are still in place. After decades as an urban wasteland (except for the souls who reside in it) Bushwick has begun a slow climb back, not to “respectability,” perhaps, but to livability. Along the way we said hello to people proud of their homes and very much aware of their history, and happy to have urban tours passing their way.

Bushwick — Beer Capital of the Northeast. Not too long ago, that was an appropriate moniker for one of Brooklyn’s oldest neighborhoods. With its large German population, the working-class neighborhood of Bushwick was home to several breweries that provided jobs and a strong economy for the community. But Bushwick’s storied history began before the beer barons settled there.

Before breweries came to Bushwick, it was a farming community where Dutch settlers grew tobacco for the local market. Later, farmers of Scandinavian, French and English descent moved to the area. Bushwick remained a farming community through the 18th century. Hessian mercenaries settled in Bushwick following the 1776 Battle of Long Island, and began a long tradition of German influence in the neighborhood. “Bushwick” comes from Dutch for “town in the woods.”

By the mid 19th century, the community of Bushwick began making the transition from a farming community to a commercial and industrial community. The implementation of a new gravity-fed water system in 1859 provided Brooklyn with drinking water from Long Island lakes. With its low mineral content, the water was ideal for brewing. Within 30 years, 14 breweries had opened in a 14-block area in Bushwick. The community was becoming a center for American brewing. The success of the breweries also led to the construction of several mansions along Bushwick Avenue, which served as homes for the neighborhood’s industrial magnates.

NYCgov.com

The tour met at Freedom Triangle, where Bushwick, Myrtle and Willoughby Avenues meet. The triangle contains the first of two war memorials along Myrtle Avenue alongside the el structure. Both are works of sculptor Pietro Montana. The “Angel of Victory With Peace” was installed here in 1921 and honors Bushwick’s 93 casualties in World War I.

In his book about NYC war memorials, Out of Fire and Valor, author Cal Snyder comments:

She appears to us to be wearing the crown of Victory, sword hilt forward and face transfigured. Her arm uplifted in a torch-like gesture to the vision of peace — the supposed end for which the Great War was fought, by America at least. The ninety-three dead who were sacrificed to it are carved on the handsome pedestal.

The tour set out under the abandoned steelwork of a section of the Myrtle Avenue El, and the decaying hulks of once-grandiose architecture. Along Myrtle Avenue between Lewis Avenue and Broadway are the last remains the Myrtle Avenue line that ran west and crossed the Brooklyn bridge to Park Row in Manhattan. This particular el structure and tracks opened April 27, 1889. The old Broadway station on the el, also no longer used, sits atop the Broadway el. The oldest el structure actually in use (1893) is part of the Broadway-Jamaica el and runs over Fulton Street between Alabama Avenue and Cypress Hills.

I do not know why this section was never torn down, but it may have something to do with the structural integrity of the remaining Myrtle el structure that sits above the Broadway el. A flyaway track connects the two lines — the Myrtle Avenue el remains in place between here and Wyckoff Avenue, where it switches to Palmetto Street on the way to Metropolitan Avenue.

Above right: The William Ulmer Mansion at Bushwick and Willoughby, which later belonged to explorer Frederick Cook, who claimed to be the first person to reach the North Pole, has been rehabilitated and is now occupied after years of moribundity. The mansion had previously been occupied by brewer Ulmer, whose nearby brewery complex on Beaver and Belvidere Streets (see below) has recently been landmarked by the city Landmaks Preservation Commission. Ulmer also built a long-vanished amusement park in Bath Beach, which today is remembered by the Ulmer Park bus repair facility and storage yard at 25th and Harway Avenues and by the Ulmer Park Library.

Name those cars! On Myrtle Avenue between Bushwick and Broadway a collector has amassed a collection of classic vehicles.

ForgottenFan Mark Nahmias: They are: a ’65 Ford Falcon, a ’49 or 50 Chevrolet, a ’53 or ’54 Chevrolet, a ’53 Chevrolet (the tail lights distinguish it from the ’54), a ’55 or ’56 Pontiac Safari (very rare), and another ’53 Chevrolet.

ForgottenFan Brian Deck: Pic 1: 1965 Ford Falcon. Pic 2: The yellow car is a 1951 Chevrolet, and the turquoise car to the right is a 1954 Ford. Pic 3: 1954 Chevrolet. The grill is gone, but the chrome around the headlights is 1954, so I’ll go with that. Pic 4: 1956 Pontiac Safari. This was Pontiac’s version of Chevrolet’s Nomad sport wagon. Pic 5: 1953 Chevrolet Bel Air.

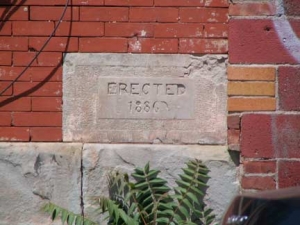

On Arion Place near Broadway is the hulk of the old Arion Mannerchör, Bushwick’s foremost German “singing society,” an organization promoting German culture. It later became a mansion and catering hall, but these days it has been converted to apartments (when I first visited in 1999, the building was in decrepit shape). The building is rich in detail of its musical past with initials at the very top and lyre-shaped ironwork on the fire escapes. Arion was a lyre player in the classic Greek stories, and lyre-ish metalwork can be seen on the fire escapes. The cornerstone reveals an 1886 construction date.

From a distance, I thought the leg was real.

Ulmer Brewery

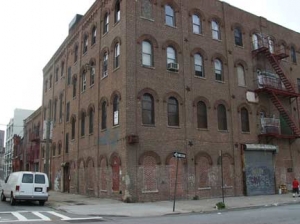

Vigelius and Ulmer’s Continental Lagerbier Brewery (later the William Ulmer Brewery) was constructed in 1872 ay Belvidere and Beaver Streets by architect Theobald Engelhardt. It was recently granted landmark status by NYC’s Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Born in Wurttemberg in 1833, William Ulmer immigrated to New York in the 1850s to work with his two uncles, Henry Clausen Sr. and John F. Betz, in the brewing industry, eventually becoming the brewmaster for Clausen’s very successful New York firm. In 1871, Ulmer partnered with Anton Vigelius to form the Vigelius & Ulmer Continental Lagerbier Brewery on Belvidere and Beaver Streets in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Born in Bavaria, Anton Vigelius immigrated to Brooklyn in 1840 at the age of 18 and was involved in the produce business prior to opening the brewery. He purchased land at the corner of Beaver and Belvidere Streets from Abraham and Anna Debevoise in 1869. In 1877 Vigelius sold his share of the brewery to Ulmer. The building ceased to be used as a brewery at the dawn of Prohibition in 1920. Though compromised by time, its arched windows and details such as tie-rod caps stand the test of time. Currently awaiting true renovation, it’s home to offices and light manufacturing.

A “mansarded, cast-iron crested house” and a “Little Italianate castle of brick and terra cotta” with an ornate driveway gate over Belgian blocks and a courtyard, wagon house stable in the rear, this is the former offices of the nearby Ulmer Brewery complex. It has recently been owned by a stone sculptor and marble worker and later, furniture designer/restaurateur Zeb Stewart. In the central bay, molded terra-cotta ornaments “Office” and the brewery’s trademark “U” identify the building’s original function and owner. Note the then-current syle of maintaining a period after a title, even on a building front. The New-York Times. has lost both its hyphen and period over time.

Whoosh! Hydrants were open all along the tour route on a 90-degree afternoon, and some ForgottenFans and ForgottenDogs jumped right in.

Bushwick Ghosts

The Rheingold Gardens stand on ground on Bushwick Avenue formerly occupied by the Rheingold Brewery. It held 35% of the state’s beer market between 1950 and 1960, whilebeer drinkers voted each year on the young lady who would be featured as Miss Rheingold in advertisements. In the 1940s and 1950s in New York, “the selection of Miss Rheingold was as highly anticipated as the race for the White House.” Rheingold advertised on the Nat King Cole TV show when other companies stayed away and aired TV commercials with Latin and African-American actors, along with personalities like John Wayne, Jackie robinson and the Marx Brothers. The Rheingold brewery closed in 1976, and the brand was revived in 1999 with a new Miss Rheingold campaign. This time instead of white gloves Miss Rheingold pageanteers wore piercings and tattoos. Miss Rheingold awaits another revival, since Kate Duyn was the last winner in 2003.

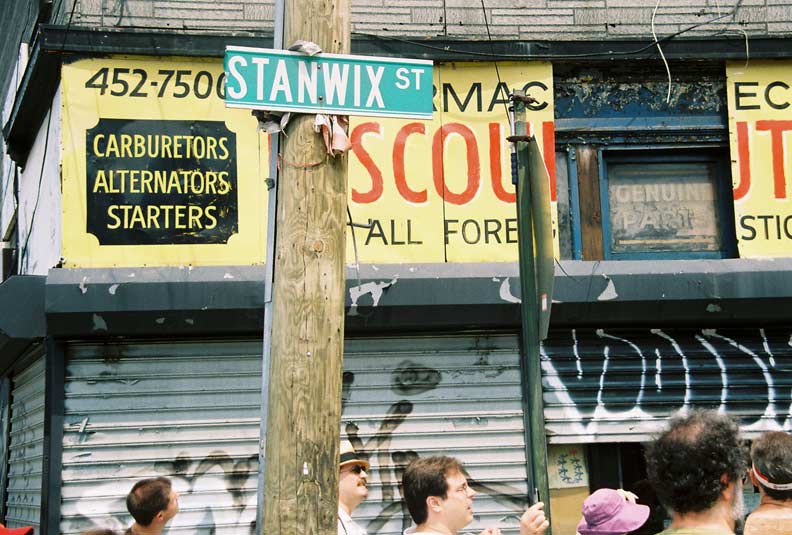

Making our way down Bushwick Avenue, at Stanwix Street we spotted an old manufacturing loft with KNITWEAR chiseled below the roof, and two ancient awning signs, one on painted wood covering an older one made of etched glass. 70 or 80 years ago, someone slaved over this sign and might be amused to know an urban tour pointed it out when it was revealed after bieng covered for decades.

Stanwix Street is named for British General John Stanwix, who helped build Fort Stanwix in Rome, NY. The street acquired the name during World War I when local German street names were expunged from the map; for example, Hamburg Avenue became Wilson Avenue, for the president at the time, and Bremen Street became Stanwix.

Unlike, say, Park Slope, Clinton Hill or Brooklyn Heights, Bushwick in the 19th century was economically mixed, with middle-class rowhouses, upper-class mansions and working-class tenements existing side by side. Many, although not all, of the mansions belonged to brewers. These brewers also endowed some of the neighborhood’s most majestic churches. Since Germany is part Protestant and part Catholic, the neighborhood boasts both St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church and the breathtaking, Spanish-baroque style St. Barbara’s Roman Catholic Church.

A wealth of copper verdigris can be seen on both the tall steeple and the roof of the school next door. Note the German inscription on the cornerstone and the date of construction, 1892. Come back when the scaffolding is off!

Next door, on the corner of Troutman and Bushwick, and on Troutman, are some magnificent ruins that apparently haven’t been touched in decades. Do they belong to St. Mark’s?

The several blocks on Bushwick Avenue south of Myrtle Avenue feature attached multifamily homes, some in their oiginal condition, some resided, and others in ruin left over from the bad old days of the 1970s and 1980s. These are interspersed with mansions built by local beer barons — some of these large, some more modest.

The corner building at Bushwick and Suydam Street has been given an unusual maroon and cream paint job. At Hart Street, an impressively corniced building sports aluminum siding. A brewer’s mansion at Cedar Street features a shady porch, and a homeowner applies a touch up near DeKalb Avenue.

7/17: the white and black building is home to a number of artists — the dwelling is featured in this NY Times article.

You will have to use your imagination as the DeKalb Library in 2010 is in the midst of roof repairs and is completely covered in scaffolding. It was designated in 2004 as a NYC Landmark and will reopen in December 2010.

You will have to use your imagination as the DeKalb Library in 2010 is in the midst of roof repairs and is completely covered in scaffolding. It was designated in 2004 as a NYC Landmark and will reopen in December 2010.

The Brooklyn Public Library’s DeKalb Branch was constructed in 1904-05 as one of the first branch libraries built in the Borough of Brooklyn with the money provided by Andrew Carnegie’s multi-million dollar gift. The neighborhood’s tremendous population growth during the last decade of the nineteenth and first decade of the twentieth century necessitated a variety of civic services including a public library. The DeKalb Branch was the first of five library designs by noted architect William B. Tubby, who served on the Architects’ commission for the Brooklyn Carnegie branches. This building followed the stylistic guidelines agreed upon by that group: a free-standing, brick and limestone building in the Classical revival style.

Its double-height windows provided much light and air for the users of the building while the rounded apse at the rear allowed for a spacious, two-story area for book stacks. Except when closed for renovations, the library has served this densely populated area of Brooklyn for a century, and with its recent refurbishing, continues to contribute a distinguished civic presence to the neighborhood.

NYC’s fire alarms, some of which date back to 1913 (though I am not sure if any of the originals remain) are due to be removed in the age of mobile phones. This specimen has the date of installation, 1929, embossed on the base.

I was told once what H.P., which appears on some of the older alarms, stands for, but forgot.

ForgottenFan Bruce Einsohn: The “HP” on the fire alarm box stands for “High Pressure.” Starting early in the 20th Century, certain parts of the city that were particularly vulnerable to fires (Lower Manhattan, Northern Brooklyn, Coney Island) were equipped with a special network of water mains to which were connected those fat, four outlet hydrants. Each of these networks were supplied by dedicated pumping stations that could supply water at pressures of up to 300 pounds per square inch. Certain alarm boxes in these districts had telegraph (TEL) keys by means of which the fire chief arriving at the scene (if he felt the fire was severe enough) could contact the pumping station and order it to start its pumps and supply the pressure deemed necessary.

The system was discontinued in the 1950s with the advent of more powerful pumps on fire engines. The special hydrants remained in place until theearly 2000s. A few still exist in lower Manhattan, especially around South Street Seaport.

The steeple is teetering and in need of a paint job but the South Bushwick Reformed Church, a “wedding cake white,” Ionic-columned church, built in 1853 and known as The White Church, remains a Bushwick touchstone decked out in clapboard and milk glass. The cross street is named for its first pastor John Himrod.

The Reformed Church of South Bushwick is an excellent example of the adaptation of a Georgian type masonry church, with tower, to a Greek Revival church of frame construction. Its dominant features are the classic portico and the soaring tower which rises from a square base through a handsome octagonal belfry to an octagonal spire. This type of steeple once characterized the skyline of London with its appearance on the numerous churches which the architect Sir Christopher Wren and his follower James Gibbs built to replace those lost in the Great Fire. This style of church continued as the model of many churches in England and America.

ForgottenFans across the street from the DeKalb Library. Even the local pups decided to join the tour.This Church stands in a small park on land donated in November 1851 by two of the first parishioners, Abraham and Andrew Stockholm. The original congregation was made up of families from twenty neighboring farms. The cornerstone was laid on September 13, 1852, a late date even for Greek Revival architecture. What may be the original iron gate still stands outside, with a North 13th Street address for the manufacturer.

Goodwin-Greene Building, 1080 Greene Avenue at Goodwin Place, a busy Tuscan columned-entrance building with window lunettes and muticolored trim. Said to have been owned once by the founder of the Bohack grocery chain — several Bohack buildings are still in place on nearby Flushing and Metropolitan Avenues.

Many of their stores were sold to Daitch Shopwell, which became Food Emporium. Anyone who grew up in NYC before that time remembers Bohack’s, as their stores were literally, everywhere. As for this house, few in the neighborhood now know the Bohack’s name, but the house remains as a fine example of residential architecture in a neighborhood with an eclectic mixture of architectural styles and a rich history. They need historic designation protection.

Montrose Morris in Brownstoner

Bleecker Street between Evergreen and Central Avenues. Here’s a Tudor-ific brick building that hasn’t succumbed to aluminum siding. The extra-wide opening, now a garage, may have been a stable at one time.

Architects often added fillips like lion heads with brass rings just below the roof corbelling. There was no particular purpose to this other than embellishment. Extra ornamentation fell out of fashion with the streamlined International Style in the 1950s, and it has never really come back. Cheaper housing built these days is pretty much concrete or brick blocks

Older neighborhoods throughout Brooklyn and elsewhere in NYC are punctuated by bluestone sidewalks.

One of the tallest buildings in Bushwick and one of Brooklyn’s tallest, St. Barbara’s Roman Catholic Church can be seen from all over the neighborhood. It is a gleaming white and cream twin-towered Spanish Baroque Catholic parish. It was constructed in 1910 by prolific architects Helmle and Huberty with a sizable donation by brewer Leonard Eppig — the church was named for his daughter Barbara. The parish has served a German, then Italian and now a Hispanic congregation.

St. Barbara’s is in the heart of Bushwick that was most severely affected by the devastations of the mid to late 1970s:

In the mid- to late 1970’s, fires coursed through the streets with such regularity that to enable fast evacuation, mothers often dressed their children for bed in street clothes. In the name of urban renewal, the city tore down blocks and blocks of homes, but never built the promised replacements. Packs of wild dogs were often the only signs of life on these streets, the pounding of scavengers pulling copper wire and aluminum fixtures from burned-out buildings the only sound.

The Sunday after the power blackout of July 1977, when Bushwick was devastated by more looting and arson than any other neighborhood in the city, a visiting Ecuadorean priest named Gabriel Santacruz mounted St. Barbara’s carved wood pulpit, with its fanciful representations of peacocks, squirrels and other animals, and bleakly told his dwindling congregation, “We are without God now.”

Today Father Santacruz would hardly recognize the place. Though Bushwick remains intensely poor, the neighborhood around St. Barbara’s Church is one of the least heralded and most successful urban reclamation projects in New York City…

New York Times

The tour continued down Bushwick Avenue, past more brewers’ mansions, some of which seem to feature shapes not found in Euclidean geometry.

Joe DeMarco shot his customary video of Tour 41:

Photos: Tim Skoldberg, Joe DeMarco, Mitch Waxman, your webmaster. Tour booklet design: Mitch Waxman.

1 comment

[…] ForgottenTour 41, Bushwick, Brooklyn | | Forgotten New YorkForgotten New York […]

Comments are closed.