Saturday, April 16th marked the first tour of the semi-ambitious FNY Second Saturdays tour events in which Forgotten New York, in association with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, will present one tour per month — all over town, not just in Astoria — on the second Saturday of each month through October. (Yes, April 16th was the third Saturday of the month, but we’re flexible). On this tour I was ably assisted by the GAHS’ Richard Melnick and Mitch Waxman.

The day was cold and damp, with a gusting northeast wind, but the tour was presciently scheduled for the late morning, and the predicted rain did not arrive until the tour was winding down three hours later. We traveled down Skillman Avenue, walking its near entire length from Hunter’s Point to Woodside, a distance of approximately two miles. The avenue, which runs along the southern end of the massive Sunnyside Yards and then skirts the southern edge of Sunnyside Gardens, provides a startling contrast between the workaday industrialism of its west end and the funky residential of its east end.

Skillman Avenue runs from Hunters Point in western Queens along Sunnyside Yards and then through Sunnyside Gardens, ending at Roosevelt Avenue – beginning and ending with the IRT Flushing Line, from the Hunters Point Avenue station to a point just past the 52nd St/Lincoln Street station. The avenue’s length has varied over the years – it attained its present route in the late 1910s, when it was built out as far as Roosevelt, but the portion adjoining Sunnyside Yards (which opened in 1910) as far as Harold Avenue (39th Street) was known as Meadow Street until about 1920, when Meadow Street was changed to Skillman. Meanwhile, the portion of Roosevelt Avenue under the IRT el was called Skillman Avenue as far east as the intersection with Woodside and Betts Avenue (now 58th Street) until about the same time.

Skillman is an English name though its progenitors were Dutch. There were Skillmans in England as early as the 13th Century; the name derives, like Truman, from the term “believable” or “trustworthy” individual. The first Skillman in America was Thomas Skillman, a soldier/musician under Colonel Nichols in the Duke of York’s expedition to seize New Amsterdam from the Dutch in 1664. After the Brits took over, Skillman settled in Newtown, married Sarah Pettit in 1669 and raised a family of seven sons and four daughters. All the Skillmans in North America today are believed to be descended from Thomas Skillman.

Today’s Skillman Avenue is a mixture of two definitely distinct parts, from the factories, lofts, plants and railyards of its western end to the small town, residential and somewhat funky atmosphere of its eastern end, a distillation of western Queens.

Paragon Building (49th Avenue and 21st Street)

Paragon Oil was founded by brothers Henry, Irving, Robert, Benjamin, and Arnold Schwartz. The family designed and built the first oil heaters designed for residential buildings. Paragon Oil won the U.S. government contract as the only oil company to supply Europe with fuel oil during the post-war reconstruction. Later, during the early days of the Cold War, Paragon supplied the U.S. government with oil for their submarines. The company was sold to Texaco in the late 1950s. At one time, the Paragon Oil office building here was the tallest in Queens.

Degnon Terminal (Skillman and Pearson Place)

We are passing a remnant of an extensive railroad network through this industrial area. Trains would connect from these tracks via a routing from the Sunnyside Yard over the Montauk Cutoff overpass over Skillman Avenue just north of 49th Avenue, and would run on a trunk line along Skillman and 47th Avenues with spurs along many of the side streets. A small freight lineserved warehouses of NYC’s great department stores such as Gimbels, Kleins, and Macys; some of their names can still be seen on buildings. Sunshine Bakeries, American Chicle gum and Swingline, with its famous neon sign were here as well. Swingline decamped to Mexico in the mid 1990s.

This was originally a private railroad known as the Degnon, after its originator, Michael J. Degnon. The LIRR absorbed it in 1928, and while all official rail activities ceased here in 1985, it’s still possible to run trains on some of the trackage; the connection at the Montauk Cutoff has been preserved.

Degnon also filled the valley marshes between Corona and Flushing, giving rise to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “valley of ashes” in The Great Gatsby. In 1912, his company also excavated the tunnel that was home to the Alfred Ely Beach pneumatic subway from about 40 years previous. The Degnon company laid out and graded the streets in the area surrounding the factories and warehouses served by its railroad.

Degnon trackage ran alongside the headwaters of the Dutch Kills waterway to allow shipping to unload goods.

IDC NY/American Chicle Building

Left: the International Design Center of New York building, Skillman Avenue and 29th Street.

The International Design Center of New York opened October 10, 1985 in what was originally the Loose-Wiles Biscuit Company Building, constructed in 1908 – known as the “thousand window bakery.” The original products were crackers marketed under the Sunshine Biscuits trademark distributed in tins depicting carton characters that are highly prized as collectibles today. Sunshine is now a division of Keebler and produces the popular Cheez-IT brand. Formerly, a huge Loose-Wiles Sunshine Biscuits neon sign occupied the roofline on the south and east sides, easily visible from trains emerging from East River tunnels into Sunnyside Yards. Today, the IDC NY building is home to furniture showrooms and offices of interior designers and decorators.

Right: Queens Atrium Corporate Center, Skillman Avenue and 30th Place

Occupying the old American Chicle building between Thomson, 47th Avenues and 30th Place and 31st Streets. The building was constructed beginning in 1914 and has many flourishes of the area including colorful terra cotta near the roofline. This building during World War II was also home to Ford Instruments, a subsidiary of Sperry Corporation, a contractor for the U.S. Navy, making ranging and control mechanisms for naval guns — and later the automatic computing gun sight.

Rich Melnick of Greater Astoria Historical Society (right) at Skillman Avenue and Queens Boulevard addresses ForgottenFans. This is the site of a future passenger station of the LIRR that will allow a short walk to the Queensboro Plaza (N, Q, 7) and Queens Plaza (E, M, R) subways and is part of an ambitious and expensive plan to bring LIRR trains into Grand Central Terminal and the East Side of Manhattan. Queens Boulevard was born shortly after the opening of the Queensboro Bridge, connecting it to older roads, Thomson Avenue and Hoffman Boulevard, bringing Queensboro ttraffic into the heart of the borough. Queens Boulevard and the new IRT Flushing subway lines (an elevated portion of which runs here) were the twin engines that spurred Queens’ rapid development after World War I.

Swingline Staples Building, Skillman Avenue at Van Dam street

Now home to the CityView Racquet Club, this building which fills and entire block and contains over a thousand windows, is the former home of Swingline Staples, founded by Jack Linsky in 1925 as the Parrot Speed Fastener Company, changing the name to Speed Products in 1939 and then Swingline in 1956. The company moved to this new headquarters on Skillman Avenue in 1950 Swingline was famed for its giant neon Swingline staples sign on the roof, featuring a working stapler. In 1998 Swingline eliminated its Queens factory, moving it to Nogales, Mexico. The 60 by 50-foot sign required six men working three ten hour days to pull down.

In 2002 the Museum of Modern Art was renovating its East 53rd street building and moved for a year into another Swingline building on 33rd Street north of Queens Boulevard. In a way, that was fitting because Jack Linsky and his wife Belle were collectors of fine art, including paintings by Rubens, Gerard David, and Boucher. The works were donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and can be found there in the Belle Linsky Galleries. The Linskys were also famed philanthropers, donating millions to charity. But the Swingline jobs have disappeared from the USA.

Sunnyside Gardens, north from Skillman Avenue from 43rd-48th Streets

The turn-of-the-century English Garden City movement of Sir Ebenezer Howard and Sir Raymond Unwin served as the inspiration for Sunnyside Gardens, built from 1924-1928. This housing experiment was aimed at showing civic leaders that they could solve social problems and beautify the city, all while making a small profit. The City Housing Corporation, whose founders were then-schoolteacher and future first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, ethicist Felix Adler, attorney and housing developer Alexander Bing, urban planner Lewis Mumford, architects Clarence S. Stein, Henry Wright, and Frederick Lee Ackerman and landscape architect Marjorie S. Cautley, was responsible for the project. Co-founderLewis Mumford [the long-time architecture critic at The New Yorker] was also one of the Garden’s first residents. The part of Skillman Avenue that runs through Sunnyside Gardens has been renamed in his honor.

The design of the Gardens was novel in that large areas of open space were included in the plan. Construction costs were minimized, which allowed those with limited means the opportunity to afford their own homes. Rows of one- to three-family private houses with co-op and rental apartment buildings were mixed together and arranged around common gardens, with stores and garages placed around the edges of the neighborhood. Just about every interior window in the Gardens offers a view of a landscaped commons. A typical price for a two-story attached brick house in the development cost $9,500 in 1927!

Artists and writers were also attracted to the amenities of Sunnyside Gardens ; in fact, the development in its early years was sometimes referred to as the ‘Greenwich Village annex’.” Artistic residents of the Gardens included painter Raphael Soyer, singer Perry Como and actress Judy Holliday. Crooner Rudy Vallee, NYPD Blue actress Justine Miceli, “Rhoda’s mom” Nancy Walker, and tough-guy actor James Caan also lived in Sunnyside.

The tour also paused briefly at Queen of Angels Church at Skillman Avenue and 44th Street. Built in 1965 in place of the Jakob and Katherine Huther house, built before 1900 previously a small hotel used by hunters who hunted in the Sunnyside woods. It was purchased about 1900 by the Hüther family and became their general store and residence. In addition to the general store, Jakob delivered produce door to door with a horse and wagon. He used the pond on the property to raise ducks.

Above the 44th Street entrance you will find the opening lines of the Magnificat (The Song of Mary). In the New Testament it is spoken by the Virgin Mary upon the occasion of herVisitation to her cousin Elizabeth.

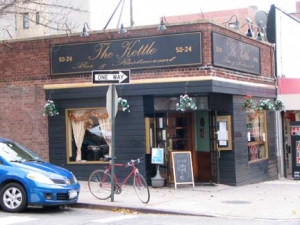

You will never go hungry or thirsty on Skillman Avenue, as just about every corner east of 46th (Bliss) Street features a pub or restaurant of some sort.

Bliss Bistro: remembers 46th Street’s former name, which in turn recollects Sunnyside founder Neziah Bliss.

Bliss, a protegé of Robert Fulton, was an early steamboat pioneer and owned companies in Philadelphia and Cincinnati. Settling in Manhattan in 1827, his Novelty Iron Works supplied steamboat engines for area vessels. By 1832 he had acquired acreage on both sides of Newtown Creek, in Greenpoint and what would become the southern edge of Long Island City. Bliss laid out streets in Greenpoint to facilitate his riverside shipbuilding concern and built a turnpike connecting it with Astoria (now Franklin Street in Greenpoint, Vernon Blvd. in Queens); he also instituted ferry service with Manhattan. Though most of Bliss’ activities were in Greenpoint, he is remembered chiefly by Blissville in Queens and by a stop on the Flushing Line subway (#7) that bears his family name.

Mathews Model Flats, 48th Street south of Skillman/Skillman Avenue, 51st-54th Streets

The streets of Long Island City, Ridgewood and to a lesser degree, Woodside, are lined with blond bricked Matthews Model Flats, each unit produced for $8000 in 1915 by Gustave X. Mathews, who is virtually unknown today but responsible for much classic residential architecture in Queens. The distinctive yellow bricks were produced in the kilns of Balthazar Kreischer’s brick works in the far reaches of Staten Island. (The Kriescher and Long Island City stalwarts, the Steinways, were linked by marriage.) By 1917, Mathews flats were in such demand that it’s said that if laid side by side the entire string of houses would reach 4.5 miles.

Mathews mass-produced these multi-unit houses for about $8,000 and sold them for $11,000. They did not have central heating or hot water systems. The only heat came from coal in the stove and a kerosene heater in the living room. Despite this, the U.S. Government gave special recognition to Matthews’ concept in 1915 when an exhibit was opened at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. It showed the world how efficiently these type of apartments met housing needs for a surging population.

Woodside Library, Skillman Avenue and 54th Street

Woodside’s Queens Library branch celebrated its centennial in 2008. It began as a traveling library collection housed in a general store, designated a branch library in 1910 and moved into its present building in 1937 – which had stood empty for four years during the Depression. A major renovation is scheduled for 2011.

We had to cut our tour short at his point — as Skillman Avenue ends at Roosevelt Avenue and 56th Street — we were initially heading north to Doughboy Park at Woodside Avenue — but as the rain had set in for good, we headed for Donovan’s of Woodside insteda, at 58th Street and Roosevelt Avenue.