The latest ForgottenTour, 47th in a series that goes back to June 1, 1999, met at 10:30AM on Saturday, August 13th in Hunters Point, narrated by your webmaster and the Greater Astoria Historical Society‘s Rich Melnick. It was the most successful ForgottenTour of the 2011 season to date as over 40 ForgottenFans signed on for 3 hours of history and walking in the sunshine. Hunters Point provides an ideal location for a ForgottenTour with its mix of new construction and buildings from a previous era hanging on for dear life; and it is both a former freight hub as well as a new ferry landing. Hunters Point has been changing rapidly since the 1990s and this tour caught it in mid-transition, as we saw precious Manhattan views that will almost certainly be more restricted, or no longer available, though the new Gantry State Park provides ample recreation space. Relics from the 1880s and 1930s stand beside immense towers being thrown up agaainst the skyline in the early 2010s.

Backdropped by a new residential tower on Vernon Blvd. and Jackson Avenue, the hulk of the old Vernon Theater, a former vaudeville joint, hosts Cafe Henri on 50th Avenue. The theatre opened in 1922 and closed in 1957. I can’t think of a nearby movie theater in 2011, actually.

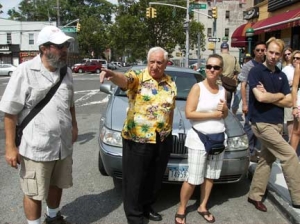

Famed Astoria photographer/documentarian Frank Corrado (center) joined the tour for a brief while and reminisced about the Vernon Theater. Here’s a short video documentary about his work.

Perps might not grasp its beauty and significance, but law-abiding tourgoers recognize the NYPD 108th Precinct on 50th Avenue as a masterpiece. The neo-baroque building was constructed in 1903. It’s worth visiting alone for its twin green entrance lanterns.

St. Mary’s Church has been a presence in Hunters Point since 1870. This 1903 church is actally the third church on the site: the previous two had been fire victims. On 49th Avenue the church is accompanied by satellite school and lyceum buildings.

The tour proceeded to Borden Avenue and 2nd Street, which was from the 1860s through 1910 the prime western Long Island rail hub, as passenger trains unloaded onto ferries that proceeded to Manhattan. The construction of the great East River bridges and then, Penn Station in Manhattan robbed it of its pre-eminence, and today the Long Island City station is mainly a train layup yard, with minimal service issuing east. The Manhattan skyline will be visible for only a short time as foundations are being laid for a new school on the river edge.

Right, the Waterfront Crabhouse, which has since 1978 occupied the ground floor of what was once Tony Miller’s Hotel, an important establishment for travelers to spend a night or wet whistles.

At 2nd Street and 50th Avenue stands the former Long Island Rail Road Powerhouse, constructed in the 1st decade of the 20th Century to power the LIRR extsnsion to Penn Station. The plant supplied 11,000-volt 25-cycle, three-phase alternating current to substations. 625 volts of direct current are carried on the LIRR’s third rails. After it ceased operations, it was occupied by Schwartz Chemical and then by an indoor tennis court. In 2005 work began converting it to expsnsive residential use, which unfortunately cost it its four distinctive coal-black smokestacks. The LIRR legacy is preserved in a manhole cover on 2nd Street.

In Gantry State Park at the river’s edge, care has been taken to preserve a measure of railroad and industrial history.

ForgottenFan Ralph Heiss:

What is called (somewhat incorrectly, yet again rather descriptively) Gantry Park, are the remains of the LIRR’s electric contained apron carfloat transfer bridges, or float bridge for short. What is left of the bridges are the uprights that contained the counterweights (inside the box girder “legs”) and the lifting “yokes” and cable drums and electric motors that raised and lowered the actual bridges that the cars rolled over from barge to land. The bridges are the part that are gone. In your first photo, the lifting yokes have been torched off just below the head house, and the second bridge with the dock built around it, has the full length of these yokes intact down to where they would have attached to the girder bridges.

We saw relics form the 1850s and 1930s that hopefully are being preserved and re-highlighted after being shunted aside for decades. Roosevelt Island, in the East River between Queens and Manhattan, had long been, along with Rikers and North Brother Island, places where the sick and the mad were stashed so respectable society wouldn’t see them. Rikers still has its jail. At left is the James Renwick Smallpox Hospital, where victimes were treated before a vaccine became widespread. Cranes are shoring up the structure, which had almost crumbled to ruin by the time city officials came to care for it.

The giant 1937 Pepsi Cola sign, which uses its old ornate script logo, lights up in red neon with the capitals P and C a full 44 feet high. When lit it’s best seen from Manhattan, but a walkway will soon open in front of it, enabling Queens-ites to get up-close and personal. The Pepsi bottling plant it advertised closed in 1999 and was razed to make way for the park.

You’ve heard of tigers in the tank but what about tigers onthe tank. The Buick was on 46th Road and Vernon Boulevard. On 47th Avenue near 11th Street stands the stepped Flemish design of Engine 258/Ladder 115. More than fifty-feet wide, the imposing façade has Flemish bond brick with burnt headers, projecting metal cant window bays, and oversized masonry details. It was designated a NYC Landmark in 2006.

PS 1 is one of the few remaining distinguished structures on Jackson Avenue. The building takes up most of a block at 21st Street, Jackson, and 46th Road a on a triangular plot. A corner clock tower was removed in the 1950s. The Romanesque Revival building went up in the 1890s and in the past decade has been reinvented to house avant-garde art in conjunction with the Museum of Modern Art.

At 45th Road and 21st Street stands what was built as Grace Methodist Episcopal Church in 1900, but is today’s Church of Christ, which as a mainly Filipino congregation (the title Iglesia ni Cristo is in Tagalog).

The Iglesia ni Cristo (INC) or Church of Christ is the only Christian religion to have started in a ‘third world’ country and successfully expanded in the west. The INC has more than 3,500 congregations worldwide in nearly 100 countries and territories. There are more than 38 congregations in the Northeastern Seaboard alone.

The Citi Tower benevolenty oversees eastern Hunters Point.

Hunters Point Historic

45th Avenue between 21st and 23rd Streets, one of Queens’ few Historic Districts, seems transplanted from brownstone Brooklyn.

Completed between 1871 and 1890, the forty-seven houses exhibit diverse architectural styles including the Italianate, French Second Empire, and Neo-Grecian. A large number of the original stoops, lintels, pediments, and other architectural details are intact. Most of these houses were built in the early 1870s for well-to-do families by two developers, Spencer Root and John Rust.

Occupying a former 200,000 square foot meter manufacturing building is 5 Pointz (formerly Phun Phactory) established by artist Pat Delillo in the early 1990s to provided street artists a way of displaying their talents without breaking the law. However, some artists argue that anarchy is a part of graffiti culture, and a legal space circumvents that mission. 5 Pointz is most visible by passengers on the #7 el, which runs behind the building.

Architectural marvels from over 80 years apart face each other on Jackson Avenue, yet they have been cleverly accentuated by the City to appear complimentary. If Queens has an iconic symbol it’s the green Citi Tower, completed for Citibank in 1989; it supplanted the Williamsburg bank Tower (1 Hanson Place) in Brooklyn as Long Island’s tallest.

The 1908 Queens County Court House (now the Queens Supreme Court building) has been in this location since 1870. When the original Beaux Arts building burned down in 1904, the current building, constructed in a similar style, was built and opened 4 years later.

Rich Melnick and Fans at the court house fountain, with the stepped Citi Tower at right.

ForgottenFan Al Kato:

Maybe I’m misreading what you wrote, but technically, the cranes supported steel bridges for unloading railroad cars directly from carfloat (barge) to shore and back. In the third picture of the park, the hoist part now buried in the decking carried two bridge structures to unload carfloats. Each of the bridges lined up with the traces of track you can see on the dock.

The whole thing was an adjustable bridge. Carfloats would ride high or low depending on weight carried, and change as they were loaded and unloaded. There would also be height differences dependent on tide and seasonal water level. There are other structures that just float (“float bridges”, though the term may apply to everything here) and are therefore self-adjusting in height. But I would think the ones shown in Gantry State Park could handle major, major loads. For example, the typical 40-foot long boxcar of the 1940s-1960s could carry about 50 tons each with the car itself weighing around 10 tons. But I’ve seen a picture of 3 diesel locomotives possibly waiting for loading – much heavier stuff. Still, locomotives would normally stay off the bridge portion, using a couple of empty flatcars to reach the railroad cars on the carfloat.

ForgottenFan Ralph Heiss:

The industrial and rail-marine historical significance of these structures is great because the one set of bridges in the first photo are of the original (Andrew) Mallory patent design, and the improved (James B.) French design, which was also found in jersey City, Weehawken, and also still rusting away in the Hudson River at Riverside Park @ 72nd Street.

The LIRR bridges are the only “restored” ones out of the 8 different sets once located around NY Harbor.

Some photographs by Joe DeMarco. Page completed 8/14/11.