By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

In November 2013, Kevin Walsh set out to document every street in the city that uses a full name. The list excluded honorific co-named streets, and streets that use two names at once (In Brooklyn, Hopkinson Avenue is also Thomas S. Boyland Boulevard, and Stone Avenue is also Mother Gaston Boulevard). It also left out two dead-end streets in Brooklyn What truly makes for a Forgotten-NY page is when one finds a full-named street that defies the surrounding grid and bears a namesake unknown to the public.

At a site to the south of Bedford-Stuyvesant, north of Crown Heights and west of Ocean Hill are two dead ends that fit the bill, along with a small park, and a third grid-defiant roadway that hearkens back to a little-known African-American village.

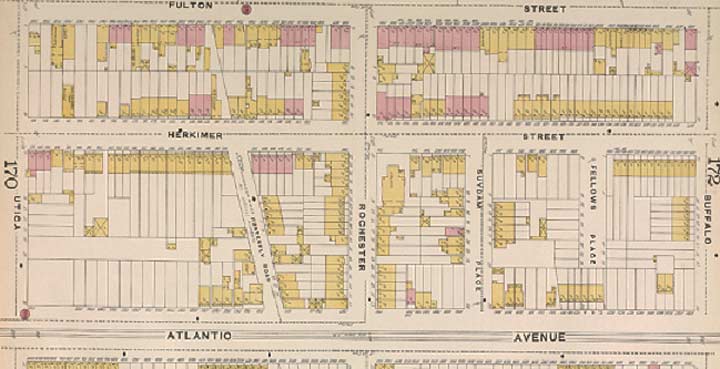

On a sliver of land bound by Bedford Avenue on the west, Fulton Street on the north, Alabama Avenue on the east, and Atlantic Avenue on the south, the grids of Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights collide with each other, resulting in numerous alleys, T-shaped intersections, and historic structures that survived for more than a century. Alice and Agate Courts were designated as a Historic District in 2009. A couple of blocks to their east are Hattie Jones Court and Jewell McCoy Lane, both of which branch off from Herkimer Street and dead-end a few yards shy of Atlantic Avenue. At their ends is Harmony Park , a fenced green space with modernist landscaping.

Information on their namesakes was very sparse online. The best that I could find was a New York Times article from 1984 that reported on the construction of attached single-family homes in what was known as Fulton Park Urban Renewal Area. In a story similar to Charlotte Street in the Bronx, this corner of Brooklyn was condemned by the city and redeveloped with middle-class homeowners in mind. It was a patch of suburban-style living within the inner city. The houses were offered at $60,000, with $5,000 expected as a down payment. 74 attached homes in total were built on these two dead-ends and on Herkimer Street. According to the newspaper, the two new streets were named for “two late community leaders.” The open space within the renewal area was developed as a park in 1990 and assigned to the Parks Department in 1997. It received the name Harmony Park during the Dinkins administration.

The southern side of Harmony Park is framed by Atlantic Avenue and the elevated structure of the LIRR Atlantic Branch. The oldest of the railroad’s branches, it has its origins in the Brooklyn and Jamaica Railroad, built in 1836, which included the tunnel in Cobble Hill. In 1905, the surface line was replaced by an elevated structure between Bedford Avenue and Ralph Avenue. With an elevated subway line running parallel two blocks to the north on Fulton Street, the only LIRR stations in Brooklyn kept in service were Atlantic Terminal, Nostrand Avenue, and East New York. The Fulton Street El was replaced by a subway line in 1940.

On the east side of Harmony Park is Boys and Girls High School, a plain modernist structure completed in 1974 as part of the urban renewal area. A mural honoring civil rights heroes adorns this otherwise uninspiring work of architecture.

Throughout the city, historical Reformed Churches serve as reminders of the Dutch colonists who founded some of the oldest neighborhoods. Historical churches affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination often represent African-American communities with deep roots in the city, founded by former slaves who founded their own self-sufficient neighborhoods. The Calvary Fellowship AME Church at the corner of Rochester Avenue and Herkimer Street represents Weeksville, the storied black community founded by James Weeks in 1835.

A former slave from Virginia who found success as a stevedore, his land purchase attracted other former slaves from the South. In the 1850s, the population numbered nearly 500, and included two African-born residents. Either they were old enough to have arrived before the 1808 foreign slave importation ban , or they were imported illegally. The last slave importation ship arrived in Mobile, Alabama in 1859. Weeksville served as a shelter for black Manhattan residents fleeing the 1863 Draft riots. The community had seven defining institutions: Colored School No. 2; Zion Home for Colored Aged People; Howard Colored Orphan Asylum; Berean Baptist Church; Bethel A.M.E. Church; Citizens Union Cemetery and the African Civilization Society. It also had its own newspaper, Freedom’s Torchlight. Weeksville had a class of professional that included the state’s first female African-American physician, and the city’s first African-American police officer.

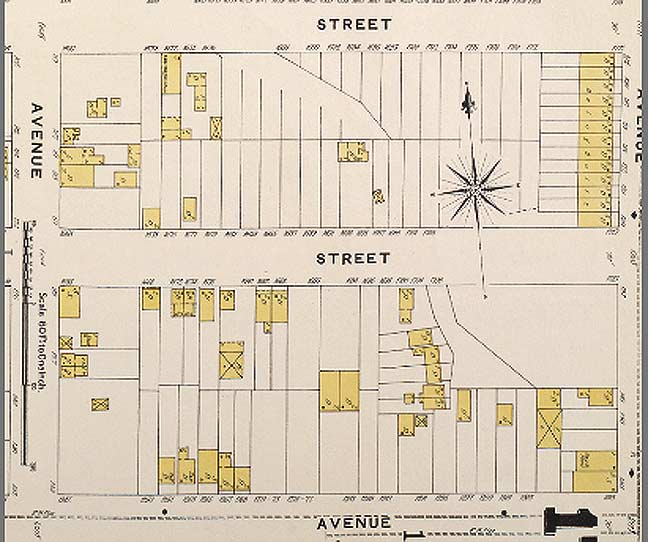

A block to the east of the Calvary AME Church is the one-block Hunterfly Place which travels askew to the grid between Herkimer Street and Atlantic Avenue. Architecture on this block is urban renewal modernist, and includes a community garden at its northern end. As one can expect, streets that defy the grid often predate it and avoided elimination because they already had buildings on them that could not be demolished when the grid was parceled out here in 1838.

Looking at an 1888 atlas plate of Hunterfly Place, we see plenty of empty lots, but the wooden houses (colored in yellow) along Hunterfly Place preserved this street.

Like Broadway in Manhattan, Hunterfly Road was a Native American trail going south towards Jamaica Bay, where seashells were collected to make wampum beads. According to the Landmarks report on Weeksville, Hunterfly is an Anglicization of the Dutch “Aander Vly” which means “to the low, or swampy, place.” The word “vly” meant a meadow or swamp. It also appears on Vleigh Place in Kew Gardens Hills, Queens. By the early 1900s, nearly all of Hunterfly Road was gone. Other than the segment at Atlantic Avenue, there was another, comprising of four homes on an alley branching off from Bergen Street, near Buffalo Avenue.

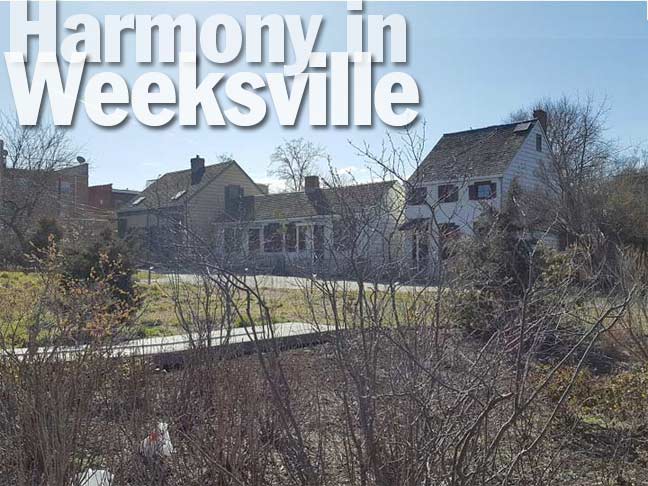

They were identified in 1968 by Pratt Institute professor Jim Hurley, who noticed their defiance of the street grid through an aerial survey.

Since then, Weeksville has returned to the public consciousness. The houses are designated as city landmarks, empty lots facing them were transformed into a farm, and in 2013, Weeksville Heritage Center was completed on the edge of the property. The facility has African-themed designs throughout, from its fence and exterior wall, to the skylight ceiling inside.

To this day, eastern Crown Heights (aka Weeksville) remains a largely African-American community. The designation of Hattie Jones Court and Jewell McCoy Lane, and preservation of Hunterfly Road ensures that the area’s black history will always have a place on the map.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press)

“Comment as you see fit.” kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com

2/24/17

1 comment

wow this is beautiful how can i be apart of this oh boy this is great gotta love my parks