LEFT: This last vestige of the Fulton Street El (the old Kings County El) supported the Franklin Avenue platform on the Franklin Avenue Shuttle until the early 1990s. Much of the el was torn down in 1940. The retained structure provided an overpass for those transferring to or from the Manhattan-bound IND Subway which runs underneath Fulton. (The shuttle proper extends off to the right of the photo.) This is original 1888 construction: the original el ran from the Fulton Ferry to Nostrand Avenue and was extended in stages, finally reaching Lefferts Avenue (Boulevard) in 1915. The El was cut back in 1940 to the section between Rockaway Avenue and Lefferts until El service was completely eliminated in 1956. Today, only the Liberty Avenue El between Grant Avenue and Lefferts Boulevard, constructed in 1915, was part of the flagship line of the Kings County RR.

Above is a 1965 view courtesy of Paul Matus.

The same site today. The overpass is a pedestrian bridge.

In 1877, the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railway was incorporated, opening the next year in 1878. It originally ran from the Prospect Park entrance at Flatbush and Ocean Avenues south to the Brighton Beach Hotel, built near the water’s edge. The BF&CI wanted to find a way to get its trains closer to downtown Brooklyn. Since a route through Prospect Park was impossible in this pre-subway era, it was decided to build a tremch through the hill at Crown Heights (then known as Crow Hill) and run the line below grade, connecting with the Long Island Rail Road tracks at Atlantic Avenue. A contractural agreement with the LIRR allowed BF&CI trains to share its trackage along Atlantic Avenue and the LIRR terminal at Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues, so the BF&CI turned left at Atlantic Avenue.

After 1882, when the LIRR took over a BF&CI competitor, the New York and Manhattan Beach Railroad, it found itself competing with itself for suburban railroad customers. The NY&MB had been created by LIRR chief Austin Corbin

before that railroading giant assumed control of the LIRR, and accordingly, the LIRR evicted the BF&CI from its trackage at the end of 1883 after just six years in service. BF&CI service was truncated to the Bedford Terminal at Frankin and Atlantic Avenues, where there was a turntable for turning the steam engines.

ABOVE LEFT: A short stretch of what may well be original BF&CI trackage can still be found, leading north beside the Franklin Shuttle’s elevated portion at Prospect Place.

No longer having a desirable northern terminal, the BF&CI was forced into bankruptcy and was reorganized in 1887 as the Brooklyn and Brighton Beach Railroad. The next year the Brighton Beach Hotel was moved inland–by railroad–to keep it from slipping into the sea. In 1896, the problem of what to do with the northern end of the line was solved when a ramp was built to connect new Kings County Elevated that ran along Fulton Street to the Brooklyn & Brighton Beach from a junction at Franklin and Fulton, bridging Atlantic Avenue and connecting to the Brighton several blocks south of that point. The Fulton elevated ran from downtown Brooklyn over Fulton Street out to Jamaica and was completed in 1893; the connection with the Brooklyn & Brighton Beach completed in 1896 was built to carry the B&BB over its old partner, the LIRR, which was still operating at grade along Atlantic Avenue. This portion of the LIRR was itself submerged in a tunnel under this part of the avenue from 1903-1905. In 1896, the same year the B&BB was leased to the Kings County Elevated, a new entity was created to unite Brooklyn’s surface and elevated lines: the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, the BRT.

Until 1899, steam locomotives were the rule on both the elevated and surface railroads. In 1899 elevated trains began running on the Brighton Line, in addition to steam service, but all steam was done away with by 1903.. In those days, surface trains did not take power from today’s third rail, but instead from overhead trolley wire. There was simply too great a risk of accidental electrocution if a third rail were to be used on the surface. Even today, unused utility poles that carried the wire still can be seen along the Franklin Shuttle’s length, a remnant of the pre-third rail and grade crossing elimination days.

Beginning in 1905, the Brighton Beach was brought to its present-day arrangement by eliminating all grade crossings. The northern part would be on an elevated structure; south of about Prospect Place, trains would run in an open cut; and south of Foster Avenue, trains would run on an embankment created from land excavated to submerge the Bay Ridge Branch of the LIRR in its own open cut. Many cross streets would be depressed to travel under the embankment, but some, such as Avenues I and X, would stop at the embankment, vexing travelers to this day. Brighton Beach BRT service continued along the parallel LIRR Manhattan Beach branch while the grade crossing elimination project was underway.

In 1913, the NYC Board of Estimate and the NY State public service commission approved a plan for subway expansion known as the Dual Subway Contracts. The Dual Contracts, named for its BRT and IRT components, expanded the NYC subway both by building new lines and incorporating older surface railroads and upgrading them by submerging them into tunnels or running them on new elevated structures.

Part of the new Dual Contracts project included a new 2-track tunnel that would run under (not through) Prospect Park under Flatbush Avenue, allowing Brighton Beach trains to continue to Manhattan along new tracks on the Manhattan Bridge. Construction proceeded slowly on this new connection, which would replace the older method of running Brighton trains along the Fulton Street El, then along the old, original BF&CI right of way, and then south to Brighton Beach. By 1918, the Brighton’s Prospect Park station had been expanded to accept both trains from the Manhattan Bridge and from the Fulton Street El. But the stage was set for both the worst accident in NYC subway history and for the orphaning of the stretch of the Brighton Beach between Prospect Park and Fulton Street.

ABOVE: One of many utility poles along the Shuttle, a remnant of pre-third rail days.

Subway motormen on the BRT had gone out on strike on Nov. 1st, 1918. Dispatchers and supervisors were pressed into service as replacement workers. That day, dispatcher Antonio Luciano was assigned as motorman on the Brighton Line that ran at that time from Park Row over the Brooklyn Bridge (which had train traffic at the time) and Fulton Street to the current Franklin Shuttle. He had never before operated elevated trains in passenger service.

Luciano had to navigate an S-shaped curve on what would later be called the Franklin Shuttle at Malbone Street. The speed limit at the location was posted as 6 MPH, but those on the scene later reported that he roared through at what must have been 50 MPH. The first car held the rails, suffering only minor damage, but the second and third cars derailed, the second being demolished and the third nearly so. About 100 passengers lost their lives, though Luciano was spared.

Soon after, Malbone Street’s name was changed to Empire Boulevard (although a portion of it remains at Montgomery Street and Nostrand Avenue).

Since that time, a signal system has been installed that goes a long way toward preventing such wrecks. It trips a brake if downhill trains exceed a prescribed limit. The S-curve is still there, but shuttle trains no longer have to negotiate it.

The BRT was reorganized as Brooklyn-Manhattan-Transit…the BMT…soon after the accident, and continued as an independent entity until 1940, when the BMT, IRT and IND subway divisions came under the oversight of New York City board of transportation, the present-day MTA. The new Flatbush Avenue tunnel under Prospect Park began service in 1920, and while the connection with the Fulton Street El was severed and the el itself out of service by 1940, the line, now called the Franklin Avenue shuttle, continued to run some trains all the way to Coney Island as late as 1963.

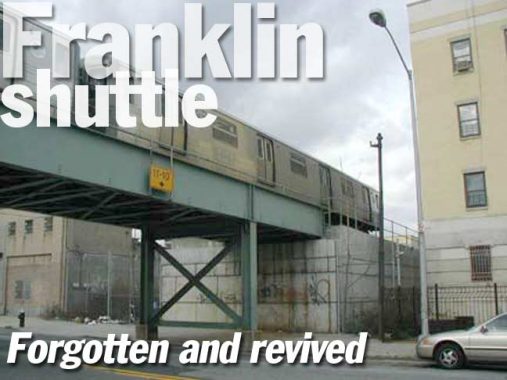

In the 1980s, the DOT proposed eliminating the Franklin Shuttle, and the line nearly closed by deferred maintenance as trackways and platforms became garbage-strewn and subway cars became unreliable and graffiti-scrawled. In the1990s the money was found to restore the line and build a transfer to the IRT at the Botanic Garden/Eastern Parkway station.

ABOVE: Car Number 726, the lead car in the fateful set in the Malbone Street Wreck. The motorman’s cab was behind the open platform at the front of the car.

What follows is a tour on the Franklin Shuttle and a look at some of its more interesting features. The line remains an entertaining anomaly among NYC subway lines.

1998:

This view was taken from the platform at Franklin Avenue and Fulton Street, where a transfer is possible to the A and C trains.

Until recently, a portion of the old Fulton Street elevated had been left standing (see photo at top of page) so passengers would use the staircase for the transfer. Today, the elevated, as well as the scene shown , is gone, as the Franklin Shuttle has now been completely rebuilt. A new staircase provides direct access to the A/C tracks under Fulton Street.

Notice the original fence and awning on the other side of the platform.

1999:

The ancient platform has been taken away and a view of Franklin Avenue can be seen from the platform.

Unfortunately, all the cast iron railings from the old platform have been removed in the renovations, as virtually everything in the station is brand new.

Additionally, the line features single-track operations between Park Place and Franklin Avenue.

A look at the Franklin Ave./Fulton St. station looking east. The abandoned platform and rubble strewn trackbed is now a memory as a complete renovation has taken place on the shuttle.

1999:

This is the same scene after 1999 renovations were complete. Franklin Avenue is now visible from the Franklin Avenue station.

Here is a 1999 view of Fulton Street and Franklin Avenue. The piece of the old Fulton El is gone (compare to photo at top of page) and in its place is the pedestrian walkway connecting the IND station with the elevated shuttle.

Colorful mosaics are becoming a large part of subway station renovations, but in 1998, they were unusual. The Franklin Avenue station renovation pioneered their use. Later, mosaics were used on the Flushing (7)and Jamaica (J, Z) lines, as well as others.

The first station stop on the Franklin Shuttle after leaving Franklin Avenue had been Dean Street, which remained open until 1996, but in an advanced state of deterioration. The station kept its old wooden platforms…some of which had holes…to the very end, along with wrought iron fencing and incandescent lighting.

The 1973 photo of a graffiti-scarred R27 (or R30) at Dean Street (which was then not as decrepit as it would later become) is courtesy of nycsubway.org.

Today, virtually nothing remains of the old Dean Street station, with the exception of the unusual placement of a streetlamp over the sidewalk on Dean Street west of Franklin. The streetlamp illuminated the bottom of the staircase leading from the old elevated platform.

Dean Street, of course, has nothing to do with 2004 Democratic frontrunner for President Howard Dean (though Dean Street intersects Howard Avenue, in an amusing coincidence, 13 blocks to the east of Franklin Avenue). However, there is a presidential candidate who has something to do with the line; at Bergen Street, alongside the shuttle, you will find an old Heinz (“57 Varieties“) factory alongside the tracks. Massachusetts Senator John Kerry married his wife Teresa in 1995; she had inherited her fortune from her deceased husband, ketchup king John Heinz, who perished in an airplane crash in 1991. Teresa had to switch her party designation from Republican to Democrat to avoid any awkwardness during the campaign.

A consist of R68 cars crosses the trestle at St. Marks Avenue. One of the old utility poles that carried electric power on the old Brighton Beach RR can be seen in the picture, and just inside the fence next to the pole can be seen ancient tracks that could be the last remnants of the old Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railroad (see photo above).

One of Charles Fletcher’s ancient ads for Castoria can be found on this building on St. Mark’s Avenue just west of Franklin Avenue. At one time, the ad must have been visible from the shuttle tracks.

On Prospect Place just west of the Shuttle you will find the old Brooklyn Jewish Hospital, which incorporated in 1901 and opened this building in 1927. Albert Einstein had surgery performed here in the early 1950s. In 1979, Brooklyn Jewish filed for bankruptcy and merged with St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in 1982 to form Interfaith Medical Center. In 2000 Interfaith relocated its entire facilty to the former St. John’s facility across the street. The old building is now being renovated for other uses, possibly as a nursing home.

Brooklyn Jewish Hospital has a poignant memory for me: here, in the summer of 1975 I visited Fred C., a classmate with whom I graduated high school. Fred was short in stature but always first in line for activities like the drama club and choir, and was a much better athlete than Your Laggardly Webmaster. Fred got ill shortly before graduation and we were devastated to hear that he had passed away at age 18. He had leukemia.

Park Place

After Dean Street, the next station stop is Park Place; Dean Street was eliminated in 1996 because of its decrepit condition (though some say Park Place was worse) as well as its proximity. From 1998-2000 the Park Place station was rebuilt from top to bottom…though some oddities and anachronisms on the street itself below the station persist.

Mission-style Park Place station house, opened in 2000

Between Sterling and Park Places, the Shuttle makes its upward journey on a ramp that had connected it to the old Fulton Street El. Its elevation today is completely unnecessary; because it would take untold millions to construct a tunnel or open cut for it, the el itself was rebuilt along its old right of way. When the grade crosing was eliminated in 1905, Park Place was depressed to allow traffic to continue uninterrupted. This placed the roadbed as much as three feet under the sidewalk, so steps and railings were built to allow entrance and exit to the roadbed.

When the station was rebuilt, the street underneath it wasn’t touched, so the 1905-era steps are crumbling away and their railings are in a rusty, collapsing condition. This is likely a small section of original railing.

This view shows the new bridge over Park Place. Note the single track operation–the only instance in the NYC subway system that this applies.

An R-68 consist enters the southbound track at Sterling Place. North of here, it’s one track only.

Seekers of ancient subway hardware can find an ancient stairway to the trackbed, as well as a rusted incandescent lamp fixture, on the overpass over Sterling Place.

From some of the trestles that cross the Franklin Shuttle south of Park Place, you can perhaps wear earplugs and drown out the street noise, and envision when the line was the old steam BF& CI. At some stretches of the line, not much has appeared to change since then.

The Consumers Park station was at the still existing Consumers Park Brewery building at Montgomery Street, not the current site of Brooklyn Botanic Garden station. The original Consumers Park station was renamed “Botanic Garden” some time after the Malbone Street wreck. In 1928 the station was closed when it was replaced by the current Botanic Garden station at Eastern Parkway. The Brooklyn Botanic Garden was constructed on the site of an old ash dump across Flatbush Avenue from Prospect Park in 1910.

The station was again rebuilt in 1998 with a drastically shortened platform only able to accommodate two 75-ft. subway cars. The renovations also exposed the brick interior of the barrel-vaulted tunnel that takes the line under Eastern Parkway, and the renovations also relocated an old Transit Police precinct to allow a transfer between the Shuttle and the IRT under Eastern Parkway.

The new Botanic Garden entrance on Eastern Parkway. The Gardens themselves are about a block to the west of the station. In the late 1990s, Eastern Parkway was reconstructed with new lampposts and stoplights inspired by Henry Bacon’s 1907 design for park lampposts. Even the bollards protecting the fire hydrants have been included in the design.

Three blocks south of Eastern Parkway, Carroll Street declines to cross the Shuttle right of way. Its place is filled by this unsual cast-iron and concrete pedestrian bridge constructed in 1994. A couple of miles to the west, Carroll Street is carried over the Gowanus Canal byanother unusual bridge.

This Gothic structure on Montgomery Street was part of the old Consumers Park Brewery complex.

More of the old Consumers Park Brewery site on Franklin Avenue south of Montgomery Street. A close look at the plaque shows the hastily-erased words “Consumers Park Brewery.” The brewery was in business between 1897 and about 1920. Ebbets Field stood a little more than a block east of the brewery.

From nyfoodmuseum.org:

A large group of hotel and saloon-keepers established this Brooklyn brewery in 1897 (for the purpose of sharing profits from brewing and selling beer). The brewery featured a recreation-like décor that included a hotel, a beer garden, and concert facilities. The company merged with the New York and Brooklyn Brewing Company and formed the Interborogh Brewing Company in 1913. Subsequently, the company sold out during the 1920s (perhaps due to prohibition). The primary organizer and first president was Herman Raub. After a dispute with the directors, he returned to the hotel business in 1907, and died in 1915 at the age of forty-six.

View of Dead Man’s Curve from Empire Boulevard, then known as Malbone Street.

Dead Man’s Curve. South of Botanic Garden, the Shuttle approaches the Prospect Park station and the site of the Malbone Street Crash. (Temporary) Motorman Luciano took the curve seen in the photo at about 50 MPH, when he should have taken it at 6 MPH. The train flew off the tracks and slammed into the tunnel wall under Malbone Street.

Today, passenger Shuttle trains do not take the curve; instead, they (slowly!) use the switch track and enter Prospect Park station on its eastern track in a one-track operation. Still, in December 1974 a Shuttle train derailed, slamming into the tunnel portal. There were injuries but no fatalities.

The Prospect Park station opened in 1905 and became an express stop in 1920 when the connection of the Brighton Beach line with the Manhattan Bridge was completed. Renovations in the late 1990s gave it these classic-type accoutrements. Across the street on Flatbush Avenue is the old Bond Bread clock tower; Bond, still in business when I was a kid, issued Brooklyn Dodgers trading cards in the 1950s.

Sources:

The Malbone Street Wreck, Brian Cudahy, Fordham University Press 1999

Headlights Magazine, Sept-Nov. 1975

The New Franklin Shuttle, Doug Diamond, thirdrail.net

BMT Brighton Line, Mark Feinman and Peggy Darlington, nycsubway.org

Art Huneke’s Brighton Line page

Original post 10/4/98; additions later