Was Dr. Frederick A. Cook the first American to climb Alaska’s Mount McKinley and the first explorer to reach the North Pole? Or, was he, as some detractors assert, a fake and a phony?

courtesy Peter Sefton

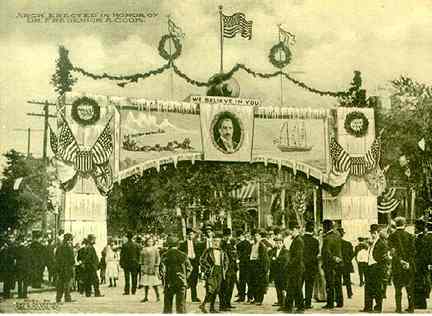

After Cook returned to the USA in the late 19-oh’s, New York City seemed to fall squarely in the pro-Cook camp, as this celebratory arch emblazoned with the words “We Believe In You” attests.

courtesy Peter Sefton

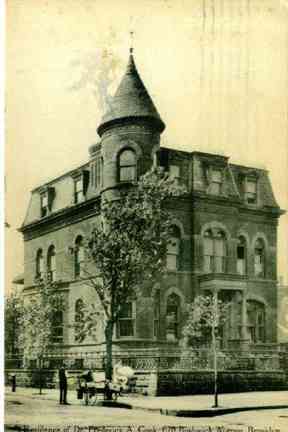

For a time, Cook resided in this mansion on Bushwick and Willoughby Avenues in Brooklyn. He died in New Rochelle, NY in 1940. The William Ulmer Mansion has been rehabilitated and is now occupied after years of moribundity. The mansion had previously been occupied by brewer Ulmer, whose nearby brewery complex on Beaver and Belvidere Streets has recently been landmarked by the city Landmaks Preservation Commission. Ulmer also built a long-vanished amusement park in Bath Beach, which today is remembered by the Ulmer Park bus repair facility and storage yard at 25th and Harway Avenues and by the Ulmer Park Library.

Whether Cook was the true discoverer of the North Pole should be left to historians to decide.

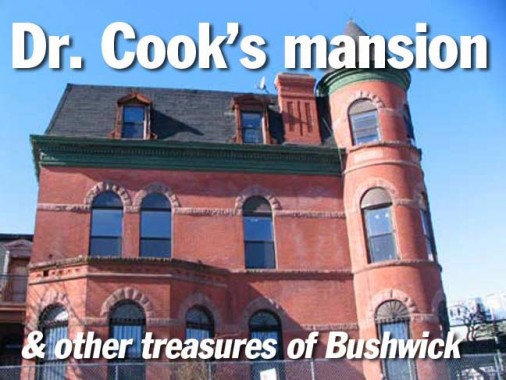

What concerns your webmaster today is his house in Bushwick, for it symbolizes this Brooklyn neighborhoods’s steep decline and efforts to revive. Today we’ll look at what became of Dr. Cook’s mansion and others along Bushwick Avenue, as well as a foray or two elsewhere in this fascinating–if little- mentioned– enclave.

Bushwick, in northeast Brooklyn, is surrounded by Bedford-Stuyvesant on the west, Williamsburgh on the north, and Ridgewood to the northeast. Like many names in Brooklyn, “Bushwick” is derived from Dutch and means “town in the woods.” Once a separate town in Kings County, it became a part of Brooklyn in 1869.

Bushwick boomed in the late 1800s when German immigrants opened large breweries in the area, which were very profitable; brewers were able to build large, imposing mansions built in the exuberant, baroque Beaux Arts style of the day. Subsequent waves of immigration brought Italians and Latinos to the area.

After the breweries closed or moved, starting in the 50s and continuing into the 70s when all were gone, Bushwick suffered a slow decline, culminating in July 1977 when, during a blackout, Bushwick , in effect, was destroyed by arson and looting. Broadway, which with Bushwick Avenue comprise the main arteries of Bushwick, are still attempting to recover from the destruction that happened in just one night. On this page we’ll look at some of Bushwick’s gems which should be the keystones in such a comeback.

In mid-2006, the planks had been removed from the windows and it appeared to be in rehabilitation. (When I went past again in 2010, it was again occupied!)

A once-grand dwelling in similar condition to Cook’s old digs was just across Willoughby Avenue. It was demolished in the early 2000s.

The triangle across from the Ulmer/Cook mansion, Freedom Triangle, contains the first of two war memorials along Myrtle Avenue alongside the el structure. Both are works of sculptor Pietro Montana. The “Angel of Victory With Peace” was installed here in 1921 and honors Bushwick’s 93 casualties in World War I. (It was restored to its lost grandeur about 5 years after this photo was taken in 2000)

She appears to us to be wearing the crown of Victory, sword hilt forward and face transfigured. Her arm uplifted in a torch-like gesture to the vision of peace — the supposed end for which the Great War was fought, by America at least. The ninety-three dead who were sacrificed to it are carved on the handsome pedestal. Both statue and setting have been recently restored, thanks to the Department of Parks Division of Art and Antiques, and Greenstreets. — Cal Snyder in Out of Fire and Valor

A bit further up Bushwick Avenue, on Meserole Street, a building’s sign testifies Bushwick Avenue’s old name: The Boulevard.

Bushwick Avenue, though, offers few more of the ruins shown above. Many of Bushwick’s old mansions are now in surprisingly good condition.

This 1890 shingle-style home, built for a Charles Lindemann in 1890, was recently restored.

The 1890 Doerschuck House was built for a brewer, as were many mansions on Bushwick Avenue.

This mansion was built for Thomas Bossert in 1898; Bossert went on to build Brooklyn Heights’ Bossert Hotel.

John Hylan, NYC mayor from 1918 to 1925, lived at 959 Bushwick Avenue (the brownstone one over from the extreme right).

Hylan paid particular attention to transit issues during his tenure (he used to operate a loco on the Brooklyn els). He opposed raising the 5-cent fare, and, some say, had a hand in nixing the expansion of subway service to Staten Island. It seems fitting, then, that Staten Island’s longest boulevard is named for him.

This house at 1080 Greene Avenue at Goodwin Place is of particular note, since it’s been allowed to deteriorate with many of its original features intact, preserved in amber, as it were.

Flecks of its original red-and gold paint job are still there on the bay window.

The first floor is used as a storefront church, but the top floors seem unused for now. By 2010, it had been given a partial makeover.

Of all Bushwick streets, Linden Street is particularly gracious. The crenellation on the mansard roof (LEFT) has been allowed to remain, while these town houses have their original iron fences, which havebeen maintained through the decades.

The South Bushwick Reformed Churchat Bushwick and Himrod dates to 1853. Note the Ionic columns. These days it could use a paint job. Himrod was the name of its first minister.

The Bushwick is not the most imposing church in the area…

…That distinction goes to St. Barbara’s Roman Catholic Church at Central Avenue and Bleecker Street. Among the tallest buildings in Brooklyn, it can be seen from all over Bushwick.

St. Barbara’s was built in 1910. A major contributor was Leonard Eppig, a local brewer whose daughter’s name was Barbara.

St. Barbara’s is, if anything, more imposing inside than out, with gilding, stonework, stained glass and a magnificent pipe organ. It should not be missed if you’re in Bushwick.

Next door to St. Barbara’s, a stained-glass house number echoes the church’s detail.

On Broadway and Arion Place is the hulk of the old Arion Männerchor, Bushwick’s foremost German singing society. It later became a mansion and catering hall.

The building is rich in detail of its musical past; German initials, top, and lyre-shaped ironwork on the fire escapes.

Oddly the fire escapes don’t appear in pictures taken from the 1940s. The hall was converted to residential use in 2003-2004 as the Opera House Lofts.

Arion Place’s former name can still be seen on an adjoining brick wall.

Vigelius and Ulmer’s Continental Lagerbier Brewery (later the William Ulmer Brewery) was constructed in 1872 ay Belvidere and Beaver Streets by architect Theobald Engelhardt. It was recently granted landmark status by NYC’s Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Born in Wurttemberg in 1833, William Ulmer immigrated to New York in the 1850s to work with his two uncles, Henry Clausen Sr. and John F. Betz, in the brewing industry, eventually becoming the brewmaster for Clausen’s very successful New York firm. In 1871, Ulmer partnered with Anton Vigelius to form the Vigelius & Ulmer Continental Lagerbier Brewery on Belvidere and Beaver Streets in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Born in Bavaria, Anton Vigelius immigrated to Brooklyn in 1840 at the age of 18 and was involved in the produce business prior to opening the brewery. He purchased land at the corner of Beaver and Belvidere Streets from Abraham and Anna Debevoise in 1869. In 1877 Vigelius sold his share of the brewery to Ulmer. The building ceased to be used as a brewery at the dawn of Prohibition in 1920. Though compromised by time, its arched windows and details such as tie-rod caps stand the test of time. Currently awaiting true renovation, it’s home to offices and light manufacturing.

A “mansarded, cast-iron crested house” and a “Little Italianate castle of brick and terra cotta” with an ornate driveway gate over Belgian blocks and a courtyard, wagon house stable in the rear, this is the former offices of the nearby Ulmer Brewery complex. It has recently been owned by a stone sculptor and marble worker and later, furniture designer/restaurateur Zeb Stewart. In the central bay, molded terra-cotta ornaments “Office” and the brewery’s trademark “U” identify the building’s original function and owner. Note the then-current syle of maintaining a period after a title, even on a building front. The New-York Times. has lost both its hyphen and period over time.

2/25/01