In 2002, Brooklyn looks seamless.

Oh, sure, there are major differencesbetween neighborhoods. Some are richer or poorer than others, and some have different racial makeups than others, speaking generally. But it’s all a grid, and all the streets eventually connect to each other.

But Brooklyn used to be a collection of six towns and within each town were small villages.

They’re still there.

1880-1900 era house (we’re guessing) on Elm Avenue, South Greenfield.

2004: RIP

A visually powerful reminder of the huge demographic and developmental gaps between Brooklyn and the rural towns [of the mid 1800s] jumps out from 19th-century maps…a thick street grid abruptly comes to an end where Brooklyn’s borders meet those of New Lots, Flatbush, and New Utrecht. Instead of streets, farm lines mark off hundreds of farms, the names of whose owners are prominently displayed….

–Marc Linder and Lawrence Zacharias, in Of Cabbages and Kings County, an account of rural Brooklyn before NYC consolidation in 1898

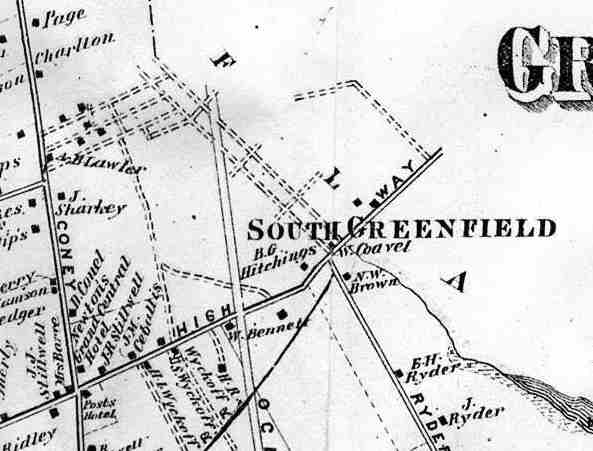

Does anything on this 1876 Beers Map of the area of Brooklyn we call Midwood look familiar? Well, Kings Highway angles through the middle of the neighborhood; it is an Indian trail that was first recorded as Kings Highway in the early 1700s (and in fact was one of a number of Kings Highways in, er, Kings County in that early era).

The two vertical lines are Coney Island Avenue, then called Coney Island Plank Road and which would eventually gain, and lose, two railroad tracks down the center, and Ocean Avenue, which was probably not laid out to any great degree as of 1876. Ryders Lane, on the bottom right, has disappeared without trace…and we’ve looked.

But it’s that collection of dotted lines above the Lawler Farm on Coney Island Avenue that concern us here, because the roads those dotted lines depict are still with us today.

The names on the map are mostly those of local landowners, though you’ll notice the “Grand Central Hotel” on Coney Island Avenue north of Kings Highway. In an era when trips of a few miles could take days, hotels and hostelries were important businesses. We are on the eastern edge of Gravesend where it borders Flatlands. Those towns would eventually be absorbed by Brooklyn, which would be swallowed by New York City in 1898.

Cleartype map by American Map Co.

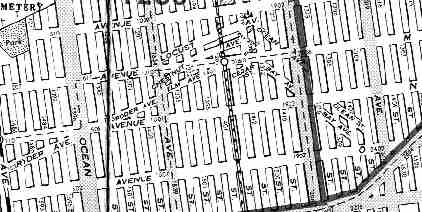

Moving forward 100 years later, to 1976, we can see that those dotted lines on the 1876 map are still there, no matter that a larger overall street grid has been superimposed.

This is the streetscape equivalent of a palimpsest in the art world, in which an earlier painting can be seen through a later one.

The old South Greenfield street pattern with four SW-NE roads, and two NW-SE roads, is still very much in place today. The four SW-NE roads were given woodsy names: Locust, Chestnut, Elm and Cedar, while the two NW-SE roads were named for water: Bay and Ocean.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any photos of South Greenfield in the very early days. But we have scouted what it looks like these days…

But before we explore South Greenfield, its name begs the question: what is South Greenfield south of? The answer lies in another part of Brooklyn that defies the grid. About a mile or so north of South Greenfield (which is centered at about Avenue M and East 16th Street), between 18th and Foster Avenues on the north and south, and 47th Street and Coney Island Avenue, a group of streets jut into the north-south street grid at an angle.

This group of streets marks a very early residential settlement carved out of the fields and farms of mid-18th Century Brooklyn, and is largely due to the efforts of one man, “Uncle” Tunis Bergen, a

farmer, an antiquarian genealogist of the Kings County Dutch, surveyor, town supervisor, of New Utrecht from 1836 to 1859, and a former Congressman whose first language was Dutch. –Linder & Zacharias, Of Cabbages & Kings County

As Flatbush town surveyor in the 1850s Bergen had surveyed the Flatbush Plank Road (now known and loved as Flatbush Avenue today) and prepared the map for the Greenfield residential project in 1852. Greenfield was a creation of the United Freeman’s Land Association, which paid $500 an acre for 114 acres. Greenfield is now known as Parkville, while a more southern settlement loosely located along Kings Highway and the Coney Island Plank Road became known as South Greenfield.

Let’s have a look at South Greenfield today. It has long been absorbed into the bustling Brooklyn neighborhood known as Midwood (derived from the Dutch name Midwout, which resembles its English translation: mid-woods).

At East 15th Street, foreground, Elm Avenue meets Avenue M as the Brighton Line (the BMT Q train, in the past and future the D train), looms in the background. Elm, a part of the original South Greenfield plan, is the oldest street in the picture. This triangle was formerly known as Dorman Square, but this name has fallen out of favor in recent decades.

Just as the confluence of Broadway and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan made the distinctive Flatiron Building possible, the interaction of East 18th Street and the diagonal Bay Avenue have necessitated the distinctive design of this apartment building, which, like the Flatiron, seems to be “sailing” into the streetscape.

As with Stuyvesant Street in the East Village in Manhattan, when you see a diagonal street making its way though an overwhelmingly regular grid, you can pretty much make the assumption that you are standing in a very old part of town where some of the original street plan survives. Here we are at Bay Avenue where it slashes across East 19th Street. Avenue M is directly ahead.

After the north-south street grid took shape, Avenue M became the main east-west artery in the neighborhood. Along Avenue M you can spot some rather rococo architecture, including this weird owl-seahorse combination. It’s just possible that the owl was added later to keep the pigeons away–a tactic that rarely works as most city pigeons can tell fake owls from real ones.

Vitagraph Studios today

Vitagraph moved to Hollywood in 1925, was sold to Warner Brothers and became Vitaphone (which name appears at the end of Warner Brothers’ classic cartoons in the 1930s and 1940s.) The old studios were used intermittently by NBC until 1959. The site is now a girls’ school. Its smokestack still stands.

Bill Cosby in 2001

This imposing building at Avenue M and East 14th Street is windowless because it contains mechanically-lit sound stages. One of the 1980s’ most popular TV shows,The Cosby Show, was taped here between 1984 and 1992 (although “Dr. Huxtable” ‘s brownstone exterior was shot on St. Lukes Place in Greenwich Village). Today it continues to facilitate the TV and movie business; the long-running soaper Another World has also called it home.

Countless TV shows have been filmed and taped in this building since 1952. The building supplanted the old Vitagraph Studio building (see story at left).

ELEMENTARY, MR. FORGOTTEN. Tracking down a lost street…

There is a suspicious indentation between apartment buildings on East 19th Street north of Avenue M. The apartments seem to follow a line parallel, and northeast of, Bay Avenue, which cuts a diagonal line across the grid.

As a matter of fact, a very old house, awaiting demolition or renovation, is turned diagonally to face that space. Clearly, there used to be a road right here. And, if you take a look at the old Beers 1876 map at the top of the page, you will indeed see twoparallel dotted lines in a NW-SE direction. As we’ve seen, the one furthest south is Bay Avenue, but what was the one on the north?

The street that used to be here is none other than Ocean Avenue.

How can it possibly be Ocean Avenue, you might say. Ocean Avenue travels in a straight, nearly north-south route between Flatbush Avenue at Prospect Park all the way down to Sheepshead Bay.

True enough, but the road parallel to, and northeast of Bay Avenue is clearly indicated on older maps (like the American Map Co. 1976 map shown above) as Ocean Avenue, as well. It was a part of the original street plan of South Greenfield, and so there already was an Ocean Avenue in place when the familiar one we know, the main artery lined with apartment buildings, was laid out in the late 1800s. Got it?

The 1935 Geographia Complete Street Guide to Brooklyn lists both Ocean Avenues (see left). And incredibly, it has the ‘other’ Ocean Avenue, the South Greenfield Ocean Avenue (at bottom) intersecting with the ‘new’ Ocean Avenue!

Over time, the South Greenfield Ocean Avenue faded away. New housing was built over the route, which was probably on its last legs when the Geographia street guide was published in the 1930s. Only the little house and the space between apartment buildings gives it away, at least in its northern section.

There is a small, southern section still thriving, however…

Thereby hangs a trail. Actually, thereby hang two trails.

Olean Street angles from East 22nd Street

Olean Street retains many of the characteristics of old South Greenfield...no sidewalks and overhanging foliage.

So if it’s not called Ocean Avenue here, why Olean?

Running north-south between Bedford-Stuyvesant and Flatbush are several streets named for prominent cities in New York state. New York itself gets the ball rolling, followed by Brooklyn (which was a separate city when the avenue was named), Kingston, Albany, Troy, Schenectady, Utica, Rochester, and Buffalo. (Strangely, Syracuse is skipped.) The order after Brooklyn seems to follow the Hudson north to Albany, and then west, roughly along Interstate 90 (the New York State Thruway) to Buffalo, but when the streets were laid out in the 1800s, the Mohawk River was likely the route followed in naming the streets.

The best educated guess I can figure is that, in order to not confuse ‘this’ Ocean Avenue with ‘that’ Ocean Avenue, it was decided to change a letter, from Ocean to Olean. Your guess is as good as mine as to why Olean, but with Brooklyn’s penchant for naming main streets after NY State towns…maybe they decided to name a little street after a little town…

Olean is a town of about 20,000 souls in western New York near the Pennsylvania border. The closest town of bigger size is Jamestown, NY, whereLucille Ball and 10,000 Maniacs came from.

HEY THERE, RYDER, RODER, YOU’RE AS WELCOME AS CAN BE

Roder Avenue (left) angles away from Avenue N at East 7th Street

Dutch families named Ryder have left a mark on Brooklyn. There is a Ryder Avenue; there used to be a Ryders Lane in Flatlands; and in the same town there is not one but two Ryder Streets. Throw in a Ryders Alley in Manhattan.

Yet, a peculiar situation exists on the western edge of South Greenfield. A Ryder Avenue angles northeast from McDonald Avenue south of Avenue N, ending at Ocean Parkway before it can intersect Avenue N. Ryder Avenue resumes again at East 7th Street at Avenue N, continuing till it ends at Coney Island Avenue.

However, as in the case of Ocean Avenue/Olean Street, it has had a letter change. Take out the Y and insert an O.

Looking through old street directories, the change from Ryder to Roder seems to have taken place sometime in the 1920s. Perhaps the mapmakers, councilmen or residents thought there were just too many streets named Ryder.

With 4 Bergens, 5 Lotts, 3 Van Sic(k)lens, etc., that little detail of multiple streets with the same name didn’t stop other Dutch families from dominating the street directories (and street necrologies) of Brooklyn.

We’ll be taking looks at the other small towns of Brooklyn soon, like Flatlands, Flatbush and the road that united them all, Kings Highway, in the Forgotten weeks to come. Same Forgotten time, same Forgotten channel.

Ryder Avenue meets Ocean Parkway just south of Avenue N

SOURCES:

Of Cabbages and Kings County: Agriculture and the Formation of Modern Brooklyn, Marc Linder and Lawrence S. Zacharias, University of Iowa Press 1999

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Blue Guide to New York City, Carol Wright, Sharon Seitz, Stuart Miller A & C Black, Ltd. 2002

BUY this book at Amazon.COM