OUR EXPLORATIONS TODAY take us to a hilly, verdant corner of the Bronx that has had many names, yet no one knows precisely what they mean. Spuyten Duyvil is tucked into the corner of the Bronx at the Hudson and Harlem Rivers, first stop beyond Marble Hill, that strange piece of Manhattan that resides on the mainland. Spuyten has always been loyally Bronx. It has been known as Speight den Duyvil, Spike & Devil, Spitting Devil, Spilling Devil, Spiten Debill and Spouting Devil, among other spellings.

In Dutch, ‘spuyten duyvil,“ the mostly-accepted spelling these days, can be pronounced two ways; one pronunciation means “devil’s whirlpool” and he other means “spite the devil.”

In Washington Irving’s Knickerbocker History, a Dutch trumpeter vows to swim the turbulent waters of (then) Spuyten Duyvil Creek where it meets the Hudson during the British attack on New Amsterdam in the 1660s “en spijt den Duyvil,” or in “spite of the devil.” The Lenape Indians inhabited the land for hundreds of years before Europeans arrived; they called the banks of the creek “shorakapok” or “sitting-down place”. After a few hundred years, the name has been pared down and exists as a street name: Kappock (pronounced kay’ pock).

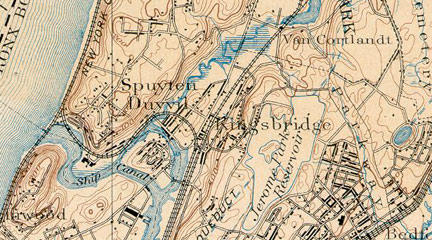

The Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Harlem River Ship Canal in 1895, temporarily making Marble Hill an island. After 1916, old Spuyten Duyvil Creek was filled in, making Marble Hill part of the mainland, though it was separated by a railroad and a steep hill from the community of Spuyten Duyvil. Marble Hill residents have successfully lobbied to politically remain in Manhattan ever since. Like the late Rodney Dangerfield, the Bronx gets no respect.

Spuyten Duyvil in the 1890s, in a New York State survey map. We see the ship canal and Spuyten Duyvil Creek, and the temporary island, Marble Hill, connected to the mainland on the north by Kings Bridge. Tibbetts Creek is shown flowing south to the creek; Tibbetts still flowed here until the 1920s, when it was relocated underground. Lastly, note the curved route the NY Central Railroad takes around the creek. After Spuyten Duyvil Creek was filled in, the NYCentral was relocated along the Harlem and Hudson Rivers, with the leftover track retained as a trainyard until the late 1960s.

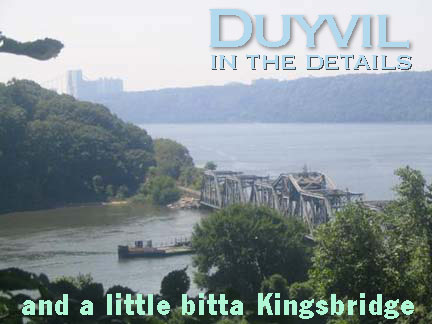

Manhattan and Spuyten Duyvil are bridged by the tolled Henry Hudson Bridge that carries the similarly-named Parkway, by the Amtrak swing railroad bridge (probably NYC’s busiest swing bridge; the Harlem is a busy waterway) and by the Broadway Bridge, that connects Manhattan with…Manhattan, carrying the IRT elevated from Inwood to Marble Hill and beyond to Van Cortlandt Park.

Edsall Avenue passes under the Henry Hudson Bridge twice, since it is a circular road emanating from Johnson Avenue, another Spuyten Duyvil curving road. It is marked as a “mapped private street” to discourage idle intruders and traffic seeking a nonexistent outlet.

Three houses on Edsall Avenue. The one on the left is the oldest and apparently dates back to 1883. Much of western Spuyten Duyvil and its northerly neighbor, Riverdale, have a rather ‘unfinished’ quality as some sidewalks are absent, wide two-lane roads suddenly narrow to one, and dead-end or proceed through in a manner not jiving with printed maps. Photos: Christina Wilkinson.

Half Moon Overlook, on Palisade Avenue, overlooks the Harlem-Hudson confluence. It is named for Henry Hudson’s ship. At left, Peter Selgin‘s Half Moon Overlook watercolor.

The view isn’t the only attraction: the rough terrain below the plaza reveals a ruined house.

Edgehill Church is not on Edgehill Avenue, a lane we will see later, but at 2550 Independence Avenue at Kappock Street. The AIA Guide to New York describes the official NYC Landmark as having “a base of Richardsonian Romanesque, a top of Gothic Revival and a smattering of Tudor details.” Suurprisingly it was designed by Francis Kimball to be a modest chapel for workers of the now-vanished Johnson Iron Foundry. Kimball also designed the brownstone Corbin Building at Broadway and John Street, now slated to remain as part of the supposed new Fulton Street Transit Hub planned for late in the 2000s. Photos: Christina Wilkinson.

Scenic Place and River Road are two small cul-de-sacs off Palisade Avenue between West 231st and West 232nd Streets; since the Department of Transportation has likely never given them street signs, we’ll lend them signs, in the Honolulu Blue the DOT formerly used on Bronx street signs that were color-coded by borough until the mid-1980s.

The remains of a River Road gatepost that looks like a cobblestoned road.

Raoul Wallenberg Forest, on Palisade Avenue across from River Road, is named for the Swedish diplomat (1912-1947) credited with saving tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from extermination by the Nazis in the World War II years by designing counterfeit passports and distributing them to Jews bound for the concentration camps. He also purchased as many houses, villas, and buildings as possible and adorned them with the blue and yellow of Sweden’s flag, thereby making them neutral diplomatic property and a safe havens for Jews.

His whereabouts became unknown in 1945. In 1957, documents were released stating he had died of a heart attack in 1947 in a Russian prison. Suspicions remain that he was killed by the KGB.

The forest was part of the 1890 James Douglas estate; a later resident was U Thant, UN Secretary-General in the late 60s and early 70s. It was converted to a public park in 1990. The thickly-wooded park is home to a European beech with a 52″ diameter trunk (left). There are also remnants of former mansions scattered about.

The spirit of Henry Hudson, it seems, seeps through Spuyten Duyvil, though the British navigator and explorer (1570-1611) apparently spent little time here when the Half Moon cruised by Spuyten Duyvil in 1609. Searching for a passage to the Pacific Ocean, Hudson wrote vividly in his log about the river that would bear his name. Hudson observed the islands that would be home to New York City, and in 1611, did find a northern passage to the Pacific when he sailed to Hudson Bay in Canada, but with disastrous consequences. His crew, Britons and Dutchmen, brawled ferociously and when they found themselves low on supplies on the frozen bay, they mutinied, setting Hudson, his son, and seven loyal crewmen adrift. Hudson presumably froze to death, while the crew starved or were killed in battles with the Inuit.

In Henry Hudson Park, at Kappock Street and Independence Avenue, you will find Karl Bitter and Karl Gruppe’s 1939 memorial, a 16-foot statue of the explorer mounted on a 100-foot shaft (that had been erected 30 years previously, on the 300th anniversary of Hudson’s visit here). Hudson and his son are shown bartering with local Native Americans in bronze relief on the base. Photos: Christina Wilkinson.

Edgehill Avenue curves in a U-shape from Netherland Avenue southeast, then north to its meeting with West 230th Street, by which time it has become a recently-paved country lane. At this point West 230th is one of the northwest Bronx’ many step streets.

2505 Palisade Avenue in the 1930s. This building has since been demolished.

Country store, 2553 Sage Place

Taken along Ewen Avenue at #2565. Images from Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York, Museum of the City of New York

Though famed 1930s New York City photographerBerenice Abbott did most of her work in Manhattan, some of her few Bronx images were taken in a neighborhood that has vanished without trace…the deep valley separating Marble Hill and Spuyten Duyvil. These evocative pictures, from her book Changing New York, show Ewen Avenue and Sage Place. Neither my newer maps of the area or my very old ones showed such streets. Then I remembered…in 1970, when I was 13 and just beginning my map collecting hobby, I had purchased a Bronx Hagstrom…

…and there I found the missing streets and neighborhood, just west of the railroad spur on the map at left. The railyards and, we presume, Irwin Avenue, Sage Place, Ewen Avenue and Leyden Place were eliminated during the 1960s or early 1970s. Compare to the 2004 map showing Johnson Avenue curving around the top of the hill by itself, under the words “Marble Hill.” Did the old neighborhood leave any trace?

Sort of. Walking along Johnson Avenue north toward West 230th, you can spot several ruined staircases, each with leftover chain link fences unsuccessfully barricading them from the sidewalk. These steps probably led down to the now-vanished Irwin Avenue. In December 2004, workmen were removing the stairs, probably as a safety precaution.

Further north, at Riverdale Avenue and West 238th (located in a particularly maddening traffic circle, unnavigable for pedestrians) you will find the Riverdale Bell Tower, inscribed with the names of every person who served in World War I from Spuyten Duyvil and Riverdale.

In 1746 a massive bell was cast in Spain and shipped to a mission in Mexico. During the US-Mexican War, between 1846 and 1848, General Winfield Scott, known to friends and foes as “Old Fuss and Feathers,” captured the bell as a spoil of war and brought it back to the US, where it was placed in a fire lookout tower at Jefferson Market at Sixth Avenue and West 9th Street in Greenwich Village. In 1884 it was moved to a Bronx firehouse located at Riverdale Avenue and West 246th Street (shown in the Berenice Abbott photo at left), where it tolled regularly at 8am, noon and 9pm. It was removed from the firehouse in 1930, when it was placed in its present home, a 500-ton stone tower designed by Dwight James Baum. The tower was moved 700 feet to the south in 1936, when the Henry Hudson Parkway was built (which also doomed the firehouse, though the company relocated to a new building.)

From Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York, Museum of the City of New York

Architect Baum signed his name on a plaque surrounded with colorful terra cotta; it is a degree of detail that has been lost in the early 21st Century.

Before exiting Spuyten Duyvil for its neighbor to the east, Kingsbridge, Broadway, the defacto border, contains some secrets: the metal sign placed on an el pillar has a picture of a bus stop sign, since the bus stop is located on a traffic island and there’s nowhere to place a sign; and some old signs, probably dating back to the construction of the el itself in the early 1900s, can be found on a building near West 230th.

Walking south on Broadway you pass the Marble Hill Houses (completed in 1952), and you are once again politically in Manhattan. A careful look, though, at one of the walls of the housing project reveals a plaque, inscribed thus:

“Northwest of this tablet within a distance of 100 feet stood the original Kings Bridge and its successors from 1693 until 1913 when Spuyten Duyvil Creek was filled up.

“Over it marched the troops of both armies during the American Revolution and its possession controlled the land approach to New York City.

“General George Washington rested at Kings Bridge the night of June 26, 1776 while en route from Philadelphia to Cambridge to assume command of the Continental Army.

“This tablet was erected by the Empire State Society Sons of the American Revolution, June 27, 1914.”

Frederick Philipse built the first Kings Bridge, a tolled span over Spuyten Duyvil Creek, in 1693. Benjamin Palmer and Jacob Dyckman built a second bridge in 1759 to avoid paying the high tolls charged by Philipse. During his retreat from the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776, General George Washington used both the King’s Bridge and Palmer and Dyckman’s free bridge to escape to White Plains. The original Kings Bridge has inspired a network of roads in Manhattan and the Bronx, some surviving, some not, named for it. The span survived till the excavations for the Harlem Ship Canal between 1913 and 1916, though the Bronx Historical Society maintains a small piece of it under Marble Hill Avenue between West 228th and West 230th Streets, in almost exactly its old position.

Crossing over the Major Deegan Expressway into Kingsbridge, the neighborhood, via West 231st Street, you find an unusual street that actually curves over the expressway, called Albany Crescent. According to historians, the crescent is an old piece of the Albany Post Road; here it intersected with Boston Post Road, and many battles during the Revolutionary War took place in its vicinity.

This part of West 231st comes to an end on Bailey Avenue, where you will find a marvelous, porched and cupola’ed Victorian era building, like something out of a dream. A close look reveals the craftsmanship of the era–take a look at the small trefoils, each reversed from the other. There’s no particular reason to do this…the architect just felt like doing it. Check the light red and green paint scheme. How come the developers haven’t found this yet and torn it down? Oops….now they might…

Late afternoon light catches the Kingsbridge Evangelical Lutheran Church, on Bailey Avenue and stepped Summit Place. A climb up the steep step street and forward 2 blocks on Summit deposits you on Kingsbridge Terrace, where you find the grand old NYPD 50th Precinct building (1912), now the Kingsbridge Terrace Community Center, complete with all kinds of Beaux Arts bric a brac.

Perot Street east of Kingsbridge Terrace

Armand Place off Perot. One of Kingsbridge Heights’ many alleys.

The Jerome Park Reservoir was built in 1906 in a design by Benjamin Church to serve the Croton Aqueduct system and holds 773 million gallons of water at capacity. The Old Croton Aqueduct actually runs under Goulden Avenue, its eastern border, and its stones are actually visible in the reservoir wall from the avenue. The reservoir was actually going to be twice as large, extending all the way east; after excavations were well under way, the plan was abandoned and that site is now occupied by Lehman College, Walton High School, DeWitt Clinton High School, the Bronx High School for Science and several subway shops and yards.

Before there was a reservoir, there was the Jerome Park Race Track, built here in 1866 by stock speculator Leonard W. Jerome (1817-1891) afer he purchased the Bathgate estate, then a part of Westchester County, in conjunction with family members and future subway builder August Belmont. Jerome’s wish was to bring back horse racing after its abolition during the Civil War. The racetrack was a lavish affair with a grandstand seating 8000, a large dining room, a magnificent ballroom, polo, trapshooting and sleighing and skating in winter; the track also boasted clubhouse accommodations comparable to a luxury hotel. The Belmont Stakes were held at the track between 1867 and 1890.

Racing came to an end in 1894 and shortly after, New York County condemned the property and built the reservoir, which had been on the drawing board since 1875. You have probably guessed that Jerome Avenue was named for the financier, but you may not know that his Brooklyn-born daughter, Jennie (1854-1921), was taken to Paris in 1867 by her mother to mingle with society; in 1874 she met Lord Randolph Churchill, they married, and their son,Winston… well, you know what he did.

Believe it or not the Kingsbridge Armory, on Kingsbridge Road between Jerome and Reservoir Avenues, was at one time considered a prime NYC tourist attraction and was advertised in subway posters by the immortal Oppy. In its heydayin the 40s and 50s it was home to bicycle races and boat shows. Of course it was built from 1912-1917 as a munitions storage area; when built it supposedly was the largest armory in the world. The interior dirt drill deck measured 300×600 feet. The Armory housed the 258th Field Artillery; the unit has its roots as a military escort for George Washington at his first inauguration.

SOURCES:

McNamara’s Old Bronx, John McNamara, Bronx Historical Society 1989

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

The Bronx in Bits and Pieces, Bill Twomey, iUniverse 2003

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

This page was photographed in September and December 2004 and composed on December 11, 2004. Special thanks to Christina Wilkinson and Bernard Ente for photography and editorial.