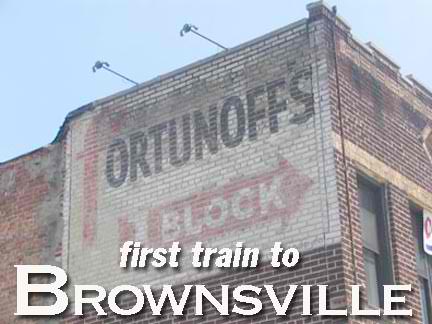

HERE are some NYC neighborhoods I find myself in again, again and again. I never tire of Coney, and I always seem to be in the Long Island City–Astoria area (the theme this year is Queens, which we’re covering from west to east as the year goes on); lower Manhattan and the Lower East Side hold a fascination; and in Staten Island it seems I’m always exploring the semi-wild areas in Great Kills and Eltingville. But there are some parts of the city where I’ve trafficked very little. For example, this was my third time ever in Brownsville and its neighbor East New York on bike or foot. The first was a bike ride in 1975, when I was taking a short cut through from my high school to Kings Highway, which I cruised back to Bensonhurst and Bay Ridge where I lived. The second was three years ago and I was there a third time in June 2005.

GOOGLE BROWNSVILLE MAP

GOOGLE EAST NEW YORK MAP

Brownsville and East New York are neighborhoods of eastern Brooklyn delineated in great part by the Bay Ridge branch of the Long Island Rail Road. In the north, Brownsville runs from East New York Avenue, on the Bedford-Stuyvesant border, south to its border with Canarsie at the railroad; East New York begins at the railroad and continues east to the Queens line at Ozone Park, with the neighborhoods of Highland Park and Cypress Hills to its north and Jamaica Bay on its south. The southeast section of East New York is called New Lots after Dutch farmers who were getting crowded out in Flatbush struck east and formed new community here in the 1670s.

Though the Dutch established some homes and farms in Brownsville and East New York in the 1700s, the area did not gel as a community until the early-to-middle 1800s. East New York was developed by John R. Pitkin, a Connecticut merchant beginning in 1835; at the time, this was the easternmost town in greater New York City, though not yet a part of the city proper. Brownsville is named for Charles S. Brown, who subdivided it in 1865.

Like many parts of NYC, Brownsville and East New York have been occupied by many nationalities. In the 1850s Germans predominated in East New York, to be followed by Italians, Russians and Poles in the early 20th Century and then by African Americans in the late 1950s. Brownsville attracted Jewish residents from Manhattan’s Lower East Side as early as the 1890s and by the Twenties, it was known as “The Jerusalem of America.” It has been the home base of Murder Incorporated, the organized crime family that included Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano; Margaret Sanger‘s first birth-control clinic; and has been home to Joseph Papp, Danny Kaye, and Mike Tyson. The area became impoverished and dangerous in the 1970s, hitting rock bottom after the lootings and riots during the 1977 blackout, but has been on a slow comeback trail, with major chain stores opening on Pitkin Avenue, joining Slavin’s Fish Market, which has been on Belmont Avenue for about 80 years.

Even Ted Nugent, the Motor City Madman, has an indirect connection to Brownsville. His second band in the 1960s, the Amboy Dukes, took its name from Irving Shulman’s 1947 novel of the same name, set on Amboy Street: the same street where Tyson grew up.

6/13/05: Ted himself has seen the page and has responded to the mention on his site’s message board, saying he was unaware of the book at the time, but yes, the title influenced the choice of band name.

The triangle of Pitkin and East New York Avenues and Legion Street was called Zion Park as early as 1911. The Zion Park War Memorial, also known as the Brownsville War Memorial, was created by sculptor Charles Cary Rumsey (1879–1922) and dedicated in 1925. It lists local war heroes who died in World War I. The space was renamed Loew Square in honor of the massive Loew’s Pitkin Theatre (see below) in 1930, but by 1997 the theatre was long shuttered and the name was changed back to Zion Triangle.

Street name mavens have plenty to chew on here in Brownsville, as many streets have changed monikers over the decades. Barrett Street was changed to Legion in the late 1930s, while Ames Street became Herzl in homor of the Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) the Austrian journalist and father of modern Zionism, a movement that led to the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. Not sure when that change was made, but it was between 1913 and 1938.

Then there’s the strange case of Douglass Street. Today confined to a six-block stretch interrupted by the Gowanus Canal between Court street and 5th Avenue, Douglass once stretched out all the way to East New York Avenue where it abruptly turned south, till it ended at East 98th Street and Hegeman Avenue. Since the early 20th Century, it has been known as St. Johns Place in Crown Heights and Bed-Stuy, while its Brownsville stretch has been called Strauss Street almost as long. Union Street today follows the same east, then south route.

Stone Avenue was renamed for beloved commuinity activist Rosetta “Mother” Gaston (1885-1981) soon after her death. Gaston founded the Heritage House currently housed at Brownsville’s Stone Avenue Library on Powell Street, which is the first public library in the world devoted solely to serving children.

Finally, Pennsylvania Avenue in East New York, which connects the recently renamed Jackie Robinson (Interboro) Parkway through East New York to the Belt Parkway, was subtitled Granville Payne Avenue in 1985 to honor a local jazz musician and community leader.

LOEW’S PITKIN THEATRE

The magnificent Loew’s Pitkin, taking up an entire block on the avenue between Legion Street and Saratoga Avenue, was built in 1929 by Thomas Lamb and seated 2,827 patrons. Unfortunately, like so many of the grand theatres of the 1920s and 30s, it went out of business in the 1960s and pretty much has been left to deteriorate. It was a church and a department store for awhile.

The Pitkin was the most baroque representative of dozens of theatres in Brownsville. It’s hard to imagine it now, but there was a time when here were as many theaters in a busy neighborhood as there were grocery stores. In this neighborhood alone, there were the Palace, Supreme, Ambassador, People’s Cinema, Livonia, Lyric, Elite, Kinema, Biltmore, Premier, Embassy, Warwick, Adelphi, Gotham, Parkway, New Prospect, Montauk, Brein’s, Penn, Sutter, and Miller; all have disappeared except those whose buildings now hold churches or markets.

(RIGHTMOST) What is this on a side window? Looks like a pair of scrolls.

So many theaters in NYC and elsewhere carry the Loew’s name. But who was Loew?

Marcus Loew was a New Yorker, born on the Lower East Side to Jewish immigrants in 1870. He began an entrepreneurial career at age six, selling newspapers and fruit, sleeping in the street so he would be there first thing in the morning when people left home to get to work. He was a pioneer in filmed entertainment, opening penny arcades by 1905 in Cincinnati, hiring entertainers to warm up the audience before the organ or orchestra-accompanied silent film was shown. In the 1920s he embarked on series of business deals that resulted in the creation of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. He died relatively young, of a heart attack at 57, but he was the biggest movie mogul in the country by that time. The Loew’s organization has a hand in over 320 theaters worldwide in 2004.

While many New Yorkers pronounce his name “Lo-wee”, his actual pronunciation was simply “Lo.”

Reminiscences of the Loew’s Pitkin at cinematreasures.org

LEFT: 1960s-era bus route sign, Pitkin Avenue. RIGHT: Pitkin Avenue and Strauss Street.

Terra cotta detail and 1931 ziggurat design, Pitkin Avenue

Serious Art Deco, Bristol Street; sign perhaps posted as a caution to arsonists, Pitkin Avenue

Possible old theatre, Pitkin and Rockaway. Don’t know what that design is supposed to be, but could H. R. Giger have passed by and been inspired to create the Face Hugger for the Alien movies?

By 2004, Hyman Spitz Florists had been on 1685 Pitkin Avenue near Rockaway Avenue for 105 years, and its ancient signboard looked as if it had been there almost as long. Spitz had been one of the last 19th Century florists still in business in NYC; founder Hyman Spitz may have sold flowers by pushcart on Pitkin Avenue when he went into business in 1899. It has serviced thousands of bar and bat mitzvahs, weddings and funerals; among the more notable affairs was the wedding of Donald and Ivana Trump in 1977. Spitz closed in mid-2004, taking its ancient sign with it. It had been in this location since 1915.

Every fifth lamppost used to have them: you heard them go off at noon every day if you were born in the 50s, as I was.

They were placed at the height of the Cold War when there was a Communist under every bed. They were air raid sirens; the Cold War legacy can still be seen on myriad apartment buildings around town that still sport “Fallout Shelter” signs. In reality, an H-bomb would likely flatten the entire northeast, rendering “duck and cover” exercises and fallout shelters superfluous. You’d be dead anyway.

I suppose I liked it better when our enemies were more easily identified…

This one was spotted at the Sutter Avenue el station at Livonia Avenue. More on the subways later…

Pitkin and Thatford Avenues

“J. Solovei” molding, possibly the builder, Pitkin Avenue

In Brownsville businesses can change hands quickly; rather than replace signs, owners frequently just paint out a couple of letters. There are still a number of old pawnshops lining Pitkin.

In Brownsville we’re reminded that even buildings containing the most mundane of businesses — whatever the businesses were — were built with a sense of style, with interesting detail; these are all on Pitkin just west of Mother Gaston Blvd.

Remains of Brein’s Theatre and Rubel Brothers, Pitkin west of Powell

Remains of a saloon at Pitkin and Powell. How can you tell? From the presence of what may have been a side window, which facilitated takeout! Buckets of beer would be passed out the window, so it wouldn’t have to be slopped past bar patrons. P.J. Clarke’s in Manhattan had a similar arrangement.

The “stubway” here at Pitkin and Van Sinderen Avenues is a part of the old Fulton Street El, which, at its greatest length, ran from Fulton Ferry at the waterfront all the way to Ozone Park. From a junction at East New York with the Broadway El and Canarsie El, it ran in two sections down Van Sinderen and Snedeker, turned east on Pitkin and then Liberty Avenues. The western end of the el was discontinued in the 1940s, while the eastern end on Liberty Avenue was joined to the IND running under Pennsylvania and Pitkin Avenues in the 1950s.

The section of the Canarsie Line over Snedeker was retained until the late 1990s.

The Sutter Avenue station (see air raid siren above) retained many ancient anachronisms until recently, including wooden platforms and crook-neck platform lighting and cast iron railings. Photo from the 60s by Joe Testagrose, from nycsubway.org

Today the Sutter Avenue station retains some of its archaisms, inclusing a wrought-iron fenced crossover on wooden planks. The Bay Ridge branch of the Long Island Rail Road runs adjacent to the station on Van Sinderen Avenue (above left). However, the air raid siren has been removed.

Pitkin east of the Canarsie Line, the heart of East Brooklyn Industrial Park. Even the most mundane building can hold some surprises. Perkins must have something to do with ships or the nautical industry. The “Fisher Building” is on Pennsylvania just south of Pitkin.

Some Pennsylvania Avenue surprises. A tiled-in guitar just north of Pitkin, and on Glenmore, the onion-domed Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Church. Believe it or not, it was built as late as 1935.

A couple of interesting sights at Sutter.

South of Sutter along Pennsylvania, evidence of a former Jewish presence.

St. John Cantius at Blake and New Jersey Avenues bespeaks a Polish presence here; John of Kent (1390-1473) was a philosopher and teacher at the Jagellonian University in Krakow, Poland. At the shrine, Mary is depicted holding the church and the world.

New Jersey Avenue between Blake and Livonia is a pleasant-enough stretch of attached houses. But the bars on almost every window are telling.

East New York has a series of streets named for states, but it seems to have been implemented in a half-hearted fashion with a couple of southern states (Louisiana, Georgia and Alabama) a pair from the northeast (Pennsylvania and New Jersey) and one from New England (Vermont).

New Lots Reformed Church

The oldest building in East New York, this ancient church at New Lots and Schenck Avenues was built in 1823 by the Dutch farmers of East New York because of the inconvenience of traveling by wagon to the former nearest church, Flatbush Dutch Reformed on Kings Highway. It’s a simple country church and churchyard. The street in back of the churchyard, McClancy Place, used to be called, fittingly enough, Repose Place.

SOURCE:

The Neighborhoods of Brooklyn, John Manbeck, ed., Yale University Press 1998

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Historic Shops and Restaurants of New York, Ellen Williams and Steve Radlauer, Little Bookroom 2002

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Photographed June 6 and written June 13, 2005.

Also see Mike Epstein’s satanslaundromat for more adventures in Brownsville and East New York.

erpietri”@”earthlink.net

©2005 Midnight Fish