Subway design reached its apotheosis in the original 28 subway stations, designed by architects George Heins and Christopher LaFarge, engineered and built by William Barclay Parsons and opened to the public on October 27, 1904. The original line ran from City Hall to 145th Street and is now a part of today’s #6 line, Times Square-Grand Central Shuttle, and #1 line.

Subway design reached its apotheosis in the original 28 subway stations, designed by architects George Heins and Christopher LaFarge, engineered and built by William Barclay Parsons and opened to the public on October 27, 1904. The original line ran from City Hall to 145th Street and is now a part of today’s #6 line, Times Square-Grand Central Shuttle, and #1 line.

New York Times map of original subway, 1904.

New York Times map of original subway, 1904.

track map: Peter Dougherty

track map: Peter Dougherty

The West Side, the East Side and the Shuttle

In its original 1904 configuration, seen at left, the IRT subway had two stations at 42nd Street, at Grand Central and at then-newly renamed Times Square (formerly Longacre Square). By 1905 the subway was expanding into the Bronx; by 1908 it had reached Brooklyn, and expansion continued apace with the Seventh Avenue and Lexington Avenue lines as we know them today completed in 1918. The stretch of track beneath 42nd Street was relegated to shuttle duty. In special cases though, trains can still be switched, with some special maneuvers, between the Seventh and the Lex by using the shuttle tracks. Above is a Peter Dougherty map showing the track configurations that allow trains to do this.

The Grand Central station leaves riders at some of NYC’s prime real estate: a east 42md Street and Lexington Avenue you will find Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore’s magnificentGrand Central Terminal, built in 1913, rescued from the developers in the 1970s and restored, inside and out, in the 1990s and 2000s; the Chrysler Building; the Chanin Building; Bowery Bank, now Cipriani’s; and the Grand Hyatt (in 1980 rebuilt from the old Commodore Hotel).

The Grand Central station leaves riders at some of NYC’s prime real estate: a east 42md Street and Lexington Avenue you will find Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore’s magnificentGrand Central Terminal, built in 1913, rescued from the developers in the 1970s and restored, inside and out, in the 1990s and 2000s; the Chrysler Building; the Chanin Building; Bowery Bank, now Cipriani’s; and the Grand Hyatt (in 1980 rebuilt from the old Commodore Hotel).

photo left: Richard Panse; photo right: Peter Ehrlich

While this is the original 1904 42nd Street-Grand Central station, it reveals little of its original pedigree, since the station, now the eastern end of the Times Square-Grand Central shuttle, has been renovated repeatedly over the years. The lengthy passageway between this station and the main concourse at Lexington Avenue where there is a transfer to the #4, 5 and 6 was originally going to be a platform further east, but the plan was scrapped soon after construction. Until recently, columns could still be seen along the passageway, and the planned platform edges can still be seen in the present-day walkway. A 1964 fire claimed all of the station’s original signage.

The restoration of Times Square in the 1990s, beginning in the Dinkins mayoralty but coming to full flower under the Giuliani administration, is one of NYC’s signature achievements; those looking wistfully to the 1980s when the area was a miasmic den of pornography and crime are missing the point. An entertainment mecca since the coming of the theatres in the early 1900s, the area had always had its seedy pockets, which are always tolerable in small doses, but they had come to completely dominate by the early to mid-1970s. It took 20 years of condemnations and court battles to drive out the smut, but when it went, so did a lot of the crime. If the area seems a bit too polished, and tourist-friendly… for FNY, that’s an acceptable tradeoff.

The restoration of Times Square in the 1990s, beginning in the Dinkins mayoralty but coming to full flower under the Giuliani administration, is one of NYC’s signature achievements; those looking wistfully to the 1980s when the area was a miasmic den of pornography and crime are missing the point. An entertainment mecca since the coming of the theatres in the early 1900s, the area had always had its seedy pockets, which are always tolerable in small doses, but they had come to completely dominate by the early to mid-1970s. It took 20 years of condemnations and court battles to drive out the smut, but when it went, so did a lot of the crime. If the area seems a bit too polished, and tourist-friendly… for FNY, that’s an acceptable tradeoff.

When the 42nd Street station was built here, it was not yet the “Crossroads of the World” it was to become, and it was constructed as a mere local station. Today the original platforms are Track 1 and Track 4.

When the 42nd Street station was built here, it was not yet the “Crossroads of the World” it was to become, and it was constructed as a mere local station. Today the original platforms are Track 1 and Track 4.

When the New York Times moved here and built a massive tower, the area increased in importance and the station gained a new platform and signage. The platforms contained entrances to both the Times Tower and the Knickerbocker Hotel, each of which can still be detected today.

photo left: Jesse Chan-Norris; photo right: Dave Emanuel

It’s hard to fathom it now but there was no free transfer from the Shuttle to the BMT Broadway Line here until 1948 (this was a full 8 years after subway unification). The concourse that allows riders to transfer between the Shuttle, BMT Broadway, IRT Flushing, and IRT 7th Avenue lines has recently completed a lengthy reconfiguration, but the rest of this massive, labyrinthine station is apparently under perpetual construction. In 2001 and 2002, new art was commissioned for the station, including Roy Lichtenstein‘s Times Square Mural (seen in the distance at left).

On the block bounded by 7th Avenue, Broadway, and West 50th and 51st Streets you will find the old American Horse Exchange, dating from the late 1800s when this was a carriage trade hotbed. After several renovations it became the Winter Garden Theater by 1910. From equines to felines: it was the home of the long-running Cats.

On the block bounded by 7th Avenue, Broadway, and West 50th and 51st Streets you will find the old American Horse Exchange, dating from the late 1800s when this was a carriage trade hotbed. After several renovations it became the Winter Garden Theater by 1910. From equines to felines: it was the home of the long-running Cats.

Liliana Porter’s 1994 Lewis carroll-themed Alice: The Way Out is the station’s art piece.

50th Street uses the same typefont and amphora (two-handled jug used in ancient Greece and Rome) theme first seen at Astor Place (see Original 28 Part One).

The original Arts and Crafts Grueby Faience ID plaques remind me of a game board, with bold colors and geometric shapes. When the station was renovated in 1993-1994 tile versions of the faience sign were installed that imitate the colors, but not the style. Notice the error on the tile version: The four squares surrounding the triangles should be green, not red.

As these 1964 views show, 50th Street was among the last stations to lose its distinctive entrance and exit cast-iron kiosks.Photo left: nycsubway.org; photo right: Evelyn Hofer from New York Proclaimed

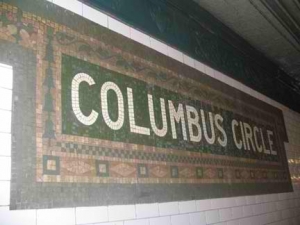

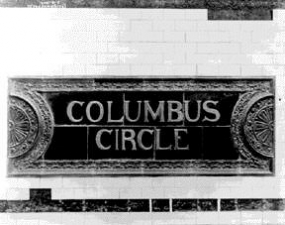

Columbus Circle has certainly seen its share of changes lately with the destruction of the old New York Coliseum and the construction of the 70-story twin-towered Time Warner Center. Edward Durrell Stone’s 2 Columbus Circle has been sold and will be drastically redesigned.

Columbus Circle has certainly seen its share of changes lately with the destruction of the old New York Coliseum and the construction of the 70-story twin-towered Time Warner Center. Edward Durrell Stone’s 2 Columbus Circle has been sold and will be drastically redesigned.

Built on a gentle curve, and full of all kinds of convex and concave walls, Columbus Circle is one of the more interesting “Contract One” stations. It’s the only one that features Grueby Faience plaques placed on corners. The plaque depicts “the great navigator’s caravel” according to The New York Subway: Its Construction and Equipment, the book published by the IRT in 1904 when the subways opened. It is likely not the Santa Maria, which was larger than a caravel and had a topsail. The plaques are surrounded by rosetts and, as we have seen at Astor Place and 50th Streets, the amphora motif. There are also simple versions of wall tapestries; more elaborate ones, as we will see, can be found a couple of stops later.

As we’ll see, the Columbus Circle station has undergone a number of changes over the years, among them being some loss of its original terra cotta and faience ornamentation. One answer has been to put back some of the old art, but in mosaic form. One of the caravels has a mosaic replacement — compare the two and see how the mosaic version stacks up to its older model.

Much of Columbus Circle was compromised when the IND subway was built intersecting it along 8th Avenue in the 1930s. Much of the station was lost so a connection to the newer subway could be made, but ample room was also left because there was a plan to make Columbus Circle an express station and convert 72nd Street to local. The platforms flange out very wide in spots as space was left for this now-scrapped objective. At photo right, we see cylindrical columns with decorative plastering at the top and bottom. This was a hallmark of IRT and BMT stations built prior to 1920.

When first built, Columbus Circle had a number of faience name tablets using the same Goudy-esque type we have seen at Astor Place and 50th Street. The semicircular faience was not duplicated elsewhere on this Contract One route, and this was a bad loss.

Some mosaic tablets do remain though, as we see at right.

A 1950s station extension has eliminated the older tile and mosaic, employing a bland sea-green scheme that is also used on uptown stations.

Original stations used intricate and elaborate moldings on ceilings. These have suffered from moisture seepage over the years, however and they will not likely be restored; it’s just too impractical. Subsequent IRT, BMT and IND stations did not get this treatment.

Lincoln Center is NYC’s premier performance space, with the Metropolitan Opera, Avery Fisher and Alice Tully Halls, the Juilliard, Vivian Beaumont and Walter Reade Theaters, among many other venues. The “travertine acropolis of music and theater” as the AIA Guide to New York City puts it, occupies three blocks between West 62nd and 65th Streets and Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues. It was begun with a turn of a spade by President Eisenhower on May 14, 1959 and cost $165 million: nearly $1 billion in today’s money, almost all of it in private contributions.

Lincoln Center is NYC’s premier performance space, with the Metropolitan Opera, Avery Fisher and Alice Tully Halls, the Juilliard, Vivian Beaumont and Walter Reade Theaters, among many other venues. The “travertine acropolis of music and theater” as the AIA Guide to New York City puts it, occupies three blocks between West 62nd and 65th Streets and Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues. It was begun with a turn of a spade by President Eisenhower on May 14, 1959 and cost $165 million: nearly $1 billion in today’s money, almost all of it in private contributions.

When subway engineers ran the line up Broadway to what became the Lincoln Square neighborhood in 1904, it was inconceivable that there would be a grand entertainment mecca this far north. Block after block of tenements lined the streets, which could be mean ones by the time West Side Story, set in the neighborhood, was written. Robert Moses was to raze a total of 18 square blocks to create Lincoln Center and public housing at the site, displacing 7,000 low-income apartments and replacing them with only 4400, according to Robert A. Caro’s The Power Broker.

A complete overhaul in the early 1990s gave 66th Streetcompletely new signage and wall decoration. Designers cleverly matched the typefonts and plaque design to original Grueby Faience specs.

A complete overhaul in the early 1990s gave 66th Streetcompletely new signage and wall decoration. Designers cleverly matched the typefonts and plaque design to original Grueby Faience specs.

You’d be forgiven for thinking it’s the original signage, but the LC — for Lincoln Center (also spelled out on the plaque) give it away. This is, though, the best rebuilt station on the Original 28.

Even our familiar amphora makes an appearance, though this will be its final one. This new version sees it at its best.

Even our familiar amphora makes an appearance, though this will be its final one. This new version sees it at its best.

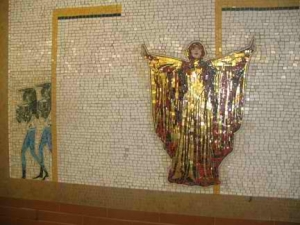

The shimmery, golden station mosaic is Nancy Speros’ Artemis, Acrobats, Divas and Dancers. It was placed here after the main renovations, in 2001.

Broadway’s most distinctive landmark in the vicinity of this station, the Ansonia Hotel, opened the same year the subway did. The grand palace, developed by W.E.D. Stokes and designed by Paul Duboy, was named for the Ansonia Brass and Copper firm. Luminaries such as Arturo Toscanini, Flo Ziegfeld, Theodore Dreiser and Igor Stravinski have lived there. Two blocks away on Central Park West is the Dakota Apartments, a pioneer when built this far north in 1884. Closer to your webmaster’s price range, we have Grey’s Papaya. How did papaya juice become associated with pig snouts?

Broadway’s most distinctive landmark in the vicinity of this station, the Ansonia Hotel, opened the same year the subway did. The grand palace, developed by W.E.D. Stokes and designed by Paul Duboy, was named for the Ansonia Brass and Copper firm. Luminaries such as Arturo Toscanini, Flo Ziegfeld, Theodore Dreiser and Igor Stravinski have lived there. Two blocks away on Central Park West is the Dakota Apartments, a pioneer when built this far north in 1884. Closer to your webmaster’s price range, we have Grey’s Papaya. How did papaya juice become associated with pig snouts?

The 72nd Street control house and Ansonia Hotel are featured in a 1905 postcard. courtesy Ed Levine

The 72nd Street control house and Ansonia Hotel are featured in a 1905 postcard. courtesy Ed Levine

The station itself is most remarkable not for what is below ground, but on the surface in the two triangle-shaped plots created by Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue and West 72nd Street.

Known officially as a control house, as in fare control, this is one of a number of Heins and LaFarge-designed station houses that appeared in the early days of the subway, which, after all, is a railroad. In its early days our urban railroad received some handsome architectural elements to go with it (others at West 96th, 103rd, 116th and 145th Streets have disappeared while the ones at Bowling Green and Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn have survived.

Known officially as a control house, as in fare control, this is one of a number of Heins and LaFarge-designed station houses that appeared in the early days of the subway, which, after all, is a railroad. In its early days our urban railroad received some handsome architectural elements to go with it (others at West 96th, 103rd, 116th and 145th Streets have disappeared while the ones at Bowling Green and Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn have survived.

Not much in the way of ceramic signage here, just the ceramic cross with the street number. Some very nice wrought iron work above the doors at each end. I didn’t take photos in the fare control area–cops swarm around at this very busy station.

At the tracks, 72nd Street preserves the best-kept example of wall mosaic tapestries. Others, not in this kind of condition, can also be seen at 110th Street. The ones at Bowling Green have been removed in favor of an orange glazed brick covering installed in the early 1970s.

At the tracks, 72nd Street preserves the best-kept example of wall mosaic tapestries. Others, not in this kind of condition, can also be seen at 110th Street. The ones at Bowling Green have been removed in favor of an orange glazed brick covering installed in the early 1970s.

At the tracks, 72nd Street preserves the best-kept example of wall mosaic tapestries. Others, not in this kind of condition, can also be seen at 110th Street. The ones at Bowling Green have been removed in favor of an orange glazed brick covering installed in the early 1970s.

A weakness of the 72nd street station in the 1990s was that even though it was constructed as an express station, no free transfer was possible from uptown to downtown. This was done because space in the control house was at a premium and the MTA was concerned about crowd control. The staircases are also quite narrow for an express station.

The condition has been alleviated by the construction, in 2002, of a second control house and a realignment of the uptown local track. Finally, uptown-downtown transfers were permitted; this is helpful in cases where local service is cancelled for trackwork. Previously you had to travel to 96th Street to cross from uptown to downtown service in cases like that.

The new control house, considered a glass, brick and metal update of the original 1904 building, was executed by Gruzen Samton and Richard Dattner and Partners. As you can see it allows a great deal of natural light to stream in, and especially on sunny days, it’s a very pleasant place to board a train. The staircases remain too narrow, however.

Broadway in the West 74th-79th Street region presents several food shopping choices: Fairway, Citarela and Zabar’s, considered by many the quintessential NYC deli, though it presents delicacies from the world over. There’s also the Starbucks where your webmaster met a blind date prompted to email him from his very first New York Times site review in 1999. As with my other blind dates, there wasn’t a second one.

Broadway in the West 74th-79th Street region presents several food shopping choices: Fairway, Citarela and Zabar’s, considered by many the quintessential NYC deli, though it presents delicacies from the world over. There’s also the Starbucks where your webmaster met a blind date prompted to email him from his very first New York Times site review in 1999. As with my other blind dates, there wasn’t a second one.

Most of 79th Street (and the following station, 86th) has been redone in a quintessentially 50s bland, monotonous tile scheme, but there are still flashes of greatness here and there. Modest wall tapestries like those at 23rd Street are the rule here. Above right: 1904 meets 1960, and 1904 always wins with that sort of matchup.

Beginning at 79th Street we see a station ID scheme that would be repeated for most of the original Contract One stations going up to 145th Street (and one stop past, the 157th Street station built in 1905: the station number flanked by two cornucopias, um, cornucopiae, um, horns of plenty. This one was unfortunately painted over. They were produced by Staten Island’s Atlantic Terra Cotta works.

Beginning at 79th Street we see a station ID scheme that would be repeated for most of the original Contract One stations going up to 145th Street (and one stop past, the 157th Street station built in 1905: the station number flanked by two cornucopias, um, cornucopiae, um, horns of plenty. This one was unfortunately painted over. They were produced by Staten Island’s Atlantic Terra Cotta works.

A surviving 79th Street mosaic station plaque.

A surviving 79th Street mosaic station plaque.

Unusually, both Brooklyn and Manhattan have busy 86th Streets. The expression “to 86” as in, “get out quick” does not arise from either; according to legend it arises from Chumley’s of Greenwich Village, 86 Bedford Street. Before it went legit it was a speakeasy during Prohibition, and when the coppers showed up, people rushed the door, or the “86”. As with the “23 skiddoo” story, take the story along with a salt shaker.

Unusually, both Brooklyn and Manhattan have busy 86th Streets. The expression “to 86” as in, “get out quick” does not arise from either; according to legend it arises from Chumley’s of Greenwich Village, 86 Bedford Street. Before it went legit it was a speakeasy during Prohibition, and when the coppers showed up, people rushed the door, or the “86”. As with the “23 skiddoo” story, take the story along with a salt shaker.

At 86th and Broadway we find the twin-towered Montana Apartments, built in 1986 and named as a counterpoint to the Dakota, 14 blocks to the southeast.

Most of 86th Street has been redesigned with bland tile (punctuated, however, with charming art pieces) but some 1904 elements are still here. The wall tapestry has been crudely tampered with; its number is gone. The number tablet is in better shape than the one at 79th.

The mosaic name tablet and other original elements that remain can be found at the southern end of the downtown station.

Surprisingly 86th preserves a good deal of its original 1904 roof plaster ornamentation.

Skipping 91st Street ( I have never been able to obtain photos of this station, closed in 1959 when 96th Street was expanded; its station art resembles that of its cohorts, 79th and 86th Streets, as nycsubway.org will show you.)

Bland towers on Broadway above, but a very interesting Contract One station below, with something for everyone including closed platforms, ID plaques and skylight remnants. North of 96th Street, a branch line was constructed that led to the northern reaches of the Bronx. An express track on the Broadway line running north from 96th Street has never, or rarely, been used for passenger service.

Bland towers on Broadway above, but a very interesting Contract One station below, with something for everyone including closed platforms, ID plaques and skylight remnants. North of 96th Street, a branch line was constructed that led to the northern reaches of the Bronx. An express track on the Broadway line running north from 96th Street has never, or rarely, been used for passenger service.

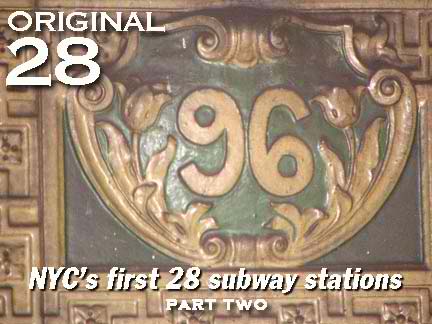

As with Brooklyn Bridge and 14th Street further down the line, side platforms originally served local trains. Unlike those two stations though, the platforms are revealed for all to see here, and a good thing too, because the side platforms preserve the mosaic station name tablets as well as the Grueby Faience “96” cartouches. These resemble the ones at Canal, Worth, Bleecker and Spring Streets in that the station letter or number is flanked by a pair of posies, tulips, in this case. Note how the 9 and 6 are simple reverses of the other. Also, note the swastika design in the plaque surrounding the number. It was an innocent symbol of good fortune in 1904.

It is inconvenient to access the 96th Street platform. Originally, you entered from a fare control house in the Broadway center median (like at 72nd Street) but as Broadway traffic increased, it was considered unsafe to allow riders to enter there, so the headhouse was closed (it’s now a community center). Riders now enter from a short portion of the side platform where there are turnstiles, and cross under the tracks, using staircases.

It is inconvenient to access the 96th Street platform. Originally, you entered from a fare control house in the Broadway center median (like at 72nd Street) but as Broadway traffic increased, it was considered unsafe to allow riders to enter there, so the headhouse was closed (it’s now a community center). Riders now enter from a short portion of the side platform where there are turnstiles, and cross under the tracks, using staircases.

Skylights from the platform shine through to the crossunder passage. They are reminiscent of early Contract One stations, which all has skylights to allow natural light into stations. This principle is again a part of new station construction proposed for the Fulton Center downtown on Broadway and at the new PATH station presently underway at Church and Dey Streets.

Only an occasional rumble here reminds riders that Bronx-bound trains pass beneath this station‘s southern end.

Only an occasional rumble here reminds riders that Bronx-bound trains pass beneath this station‘s southern end.

Early IRT mosaicists used great exactitude, along with a subtle color pallette of earth tones. This would be continued in later IRT and early BMT stations, but in the 1920s there was a color explosion with both BMT and IND construction employing brilliant yellows, blues and reds.

Early IRT mosaicists used great exactitude, along with a subtle color pallette of earth tones. This would be continued in later IRT and early BMT stations, but in the 1920s there was a color explosion with both BMT and IND construction employing brilliant yellows, blues and reds.

A look at the 103rd Street station crossover.

A look at the 103rd Street station crossover.

A tale of two mosaic name tablets, one modest, one florid.

Broadway turns northwest here and the subway follows.

Broadway turns northwest here and the subway follows.

The Grueby cartouche employs the swastika we first saw at 96th Street but dispenses with the flower theme.

The Grueby cartouche employs the swastika we first saw at 96th Street but dispenses with the flower theme.

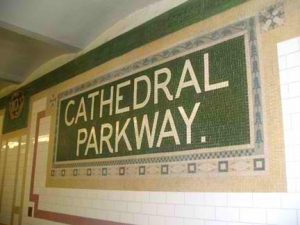

Is it Central Park North? Is it Cathedral Parkway? Or is it plain old West 110th Street? Can a local get in touch with me and tell me the preferred name. A couple of blocks north on West 112th Street you will find Tom’s Restaurant, used in external shots (with “Tom’s” carefully obscured) representing Monk’s Diner on Seinfeld; it also inspired Suzanne Vega‘s 1990 smash “Tom’s Diner.” Unbeknownst to Vega, a couple of British DJ’s spliced in instrumental backing under her originally a cappella track, and the remixed result gave her a second Top Ten, a position she has not reached since.

Is it Central Park North? Is it Cathedral Parkway? Or is it plain old West 110th Street? Can a local get in touch with me and tell me the preferred name. A couple of blocks north on West 112th Street you will find Tom’s Restaurant, used in external shots (with “Tom’s” carefully obscured) representing Monk’s Diner on Seinfeld; it also inspired Suzanne Vega‘s 1990 smash “Tom’s Diner.” Unbeknownst to Vega, a couple of British DJ’s spliced in instrumental backing under her originally a cappella track, and the remixed result gave her a second Top Ten, a position she has not reached since.

Tulips and swastikas return here on the ID cartouches.

Since the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on Amsterdam and110th was begun in 1892, and the station opened in 1904, we may assume the street was granted the moniker sometime in the intervening years.

Since subway engineer William Barclay Parsons was a Columbia trustee, you can expect to see a lot of Columbia U. references at its subway station. The massive McKim, Mead and White campus commenced construction in 1897. The university had occupied campuses near City Hall and also where Rockefeller University is now, on York Avenue in the East 60s. Until the 1960s the station had a control house in the center median.

Since subway engineer William Barclay Parsons was a Columbia trustee, you can expect to see a lot of Columbia U. references at its subway station. The massive McKim, Mead and White campus commenced construction in 1897. The university had occupied campuses near City Hall and also where Rockefeller University is now, on York Avenue in the East 60s. Until the 1960s the station had a control house in the center median.

Looking north on Broadway as far as the eye can see from 116th Street in this 1905 postcard view. courtesy Thaddeus Wilkerson.

Looking north on Broadway as far as the eye can see from 116th Street in this 1905 postcard view. courtesy Thaddeus Wilkerson.

This station features two separate ID cartouches, one with the station number and another featuring the seal of Columbia University. Each is flanked by a faience torch. Is that a snake entwining it?

Also note the baby blue station tile. The blue color is official to Columbia.

It looks like the usual IRT station mosaic tablet. But there is a subtle difference…

It looks like the usual IRT station mosaic tablet. But there is a subtle difference…

In a truly loving bit of detail, you can find an open book and an Aladdin-style lamp adjoining the “Columbia University” station name.

Riders new to the west side IRT will find it surprising to find themselves in bright sun, or at least natural light, at 125th Street when the train emerges from the tunnel onto a trestle high above Broadway. But a look at this schematic of Manhattan topography, published in the companion IRT book The New York Subway: Its Construction and Equipment will show that it really shouldn’t be so shocking.

Riders new to the west side IRT will find it surprising to find themselves in bright sun, or at least natural light, at 125th Street when the train emerges from the tunnel onto a trestle high above Broadway. But a look at this schematic of Manhattan topography, published in the companion IRT book The New York Subway: Its Construction and Equipment will show that it really shouldn’t be so shocking.

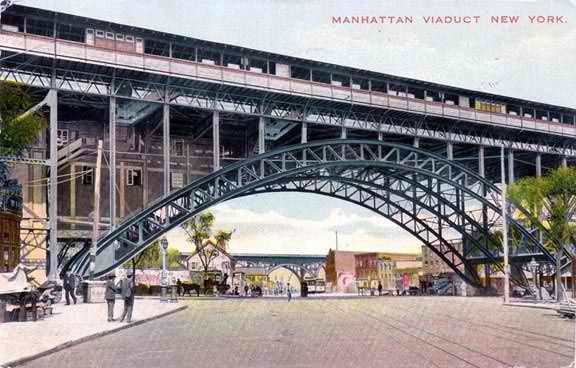

While the IRT was constructed to rise and fall with subtle topography changes, subway engineers were faced with a problem in Manhattan Valley: what to do to cross the deep rift at Manhattan (now 125th) Street? The best way was to bridge the rift, then put the train back in a tunnel on the other side. Indeed, soon after re-entering the tunnel, riders find themselves under Manhattan’s highest hills, and are required to board elevators to reach the street.

While the IRT was constructed to rise and fall with subtle topography changes, subway engineers were faced with a problem in Manhattan Valley: what to do to cross the deep rift at Manhattan (now 125th) Street? The best way was to bridge the rift, then put the train back in a tunnel on the other side. Indeed, soon after re-entering the tunnel, riders find themselves under Manhattan’s highest hills, and are required to board elevators to reach the street.

Manhattan Street station, 1905. The card is mislabeled “Manhattan Avenue.” courtesy Ed Levine

Manhattan Street station, 1905. The card is mislabeled “Manhattan Avenue.” courtesy Ed Levine

The magnificent IRT Viaduct from street level in a 1905 postcard view. It still looks much the same today. The equally impressive Riverside Drive elevated viaduct can be seen in the distance. Note the trolley tracks: some of them are still visible in the street on 12th Avenue (under the viaduct) and 125th Street (Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard). courtesy Ed Levine

The magnificent IRT Viaduct from street level in a 1905 postcard view. It still looks much the same today. The equally impressive Riverside Drive elevated viaduct can be seen in the distance. Note the trolley tracks: some of them are still visible in the street on 12th Avenue (under the viaduct) and 125th Street (Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard). courtesy Ed Levine

With and without the windscreen.

Broadway here is nothing special, just a few storage lofts. You can spot an old Studebaker studio, recognizable by its wheel logo, on West 126th between Broadway and 12th Avenue.

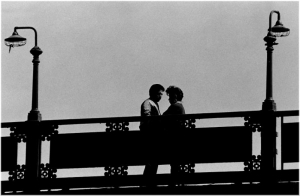

The view to the west is impressive as it contains the Riverside viaduct, and on clearer days than this, views across the mighty Hudson to New Jersey.

Station lighting harks back to its original 1904 versions. It uses the same shafts, topped by a new gooseneck mercury luminaire, replacing the dim incandescents. photo bottom: Matt Weber

We are again in the tunnel, and we come to another prestige school at this station, City College of New York, worth a trip for a view of Shepard Hall from Amsterdam Avenue and 141st Street. You’ll be glad you’re a New Yorker when you see that view, if you aren’t already.

We are again in the tunnel, and we come to another prestige school at this station, City College of New York, worth a trip for a view of Shepard Hall from Amsterdam Avenue and 141st Street. You’ll be glad you’re a New Yorker when you see that view, if you aren’t already.

Sheesh…in the early 1980s, the 137th Street station was remodeled in a contemporary scheme that makes you glad it isn’t the 80s anymore. Actually this should be preserved as a paean to Everlovin’ Eighties bad taste. Later, in 1988, the station got a further treatment with Steve Wood’s Fossils bas reliefs.

Fortunately a couple of station ID mosaic panels were preserved, though they seem totally out of place in the Jetsons-like rest of the station. The tablet is rendered in the City College lavender color; the cartouche is the three-faced City College emblem “Respice”, “Adspice”, and “Prospice.” Forgotten Fan Joe Schlesinger: “The original Spice Girls.”

The 28th station of the Original 28, 145th Street was the northern terminus on opening day, October 27, 1904. The next station to the north, 157th, would open November 12th, while stations north of that were opened in 1906.

The 28th station of the Original 28, 145th Street was the northern terminus on opening day, October 27, 1904. The next station to the north, 157th, would open November 12th, while stations north of that were opened in 1906.

SOURCES:

The New York Subway, Its Construction and Equipment,Interborough Rapid Transit 1904, 2004 reissue

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York ,Robert Caro, Vintage paperback 1975

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

3 comments

[…] the subway station, is on the National Register of Historic Places. It’s also part of the original 28 stations of the NYC subway system, designed by architects George Heins and Christopher […]

[…] it had a newsstand curiously in the same shape as the subway entrance. It’s also one of the original 28 stations designed by architects George Heins and Christopher LaFarge for the NYC subway system. Other […]

[…] West 72nd Street, but it is clearly seen as a priority because of its proximity to Lincoln Center. Forgotten NY has a good rundown of the renovations in this station as part of it’s “Original 28” series […]

Comments are closed.