When I first started researching NYC history I assumed that Sheepshead Bay was named for its one-time resemblance, in outline, to a sheep’s head.

Though Gravesend was settled by Lady Moody in 1643 it remained populated primarily by the Canarsee indians for the next few decades, and after they were gone, was frequented only by the occasional fishing party. The land was swampy and not considered a prime area for development. By 1873, homesteads had emerged along the few roads, while the area was primed for an expansion that no one had thought possible.

The eastern end of the Coney Island Boardwalk (known formally as the Riegelmann Boardwalk, for the Brooklyn Borough President when it opened in the early 1920s) is the gateway to the present-day Manhattan Beach. It must be something to live in that apartment building, especially with its western view: nothing but sea and sand all the way to the horizon. It’s on the southern end of Corbin Place.

One of the living fossils on Brighton 15th Street is a light indicating a telephone that connected directly to the local precinct. The phone is long gone and few of the lights are still in place.

Manhattan Beach Estates Associates are quite welcome to this bit of cracked concrete.

Another relic of times forgot can be found at Avenue Y and Haring Street, where there’s an old mercury-vapor park lamp. These were installed on octagonal poles to cast light on playgrounds. This one has long since lost its bulb and filament. In the late 70s and early 80s they were replaced by much brighter sodium vapor lights, and relics like this are now very rare.

Babi Yar Triangle, at Corbin Place and Brighton 15th Street, is a pleasant park with kids’ recreations, chess tables and a house across the street that looks like it was built in the colonial era.

From http://www.nycgovparks.org:

On September 29th and 30th, 1941, Nazi Einsatzgruppe soldiers, supported by members of the Ukrainian militia, massacred 33,711 Jews in the Babi Yar ravine outside Kiev, Ukraine’s capital. Over the course of the 778 days of Nazi rule in Kiev, the ravine became a mass grave for over 100,000 people. In addition to the Jewish Ukrainians, the Nazis murdered Gypsies (Roma), physically and mentally handicapped people, Soviet Prisoners of War, homosexuals, and public dissenters of the Third Reich’s activities.

Brighton Beach has been a Jewish enclave since the 1920s. A reading of Russian author Yevgeni Yevtuchenko’s 1961 poem “Babi Yar” marked the 1989 dedication of this memorial park.

The Magnate

Today the only sign of Austin Corbin’s legacy, is, well, a sign–on the street named for him. But Corbin (1827-1898), a wealthy financier of the late 19th Century, built two magnificent hotels in the area as well as the railroad that connected them with the rest of Brooklyn–spearheading the development that continues today.

left: Manhattan Beach Hotel (Merlis, Welcome Back to Brooklyn); above, Oriental Hotel (Merlis, Rosenzweig and Miller, Brooklyn’s Gold Coast).

Corbin acquired 600 acres east of what would become Coney Island Avenue east to the edge of Gravesend Neck–a tract about 2.5 miles in length… in 1875, and set about building a bulkhead, filling in the swamps, surveying a railroad from Greenpoint to what was newly named Manhattan Beach, and building the Manhattan Beach Hotel. Designed by J.P. Putnam, it opened July 4, 1877 with President Grant cutting the ribbon. The two siubsequent year saw Corbin expand the hotel into a sprawling complex, making it the premier resort on Long Island’s south shore with grand parlors and dining rooms furnished with Eastlake pieces. Evergreens and floral designs lined the resort’s pathways to the shore, lined with manmade ponds stocked with goldfish.

J.P. Sousa and Victor Herbert, riding high in the pop music of the period, frequently played Manhattan Beach, with the March King’s biggest hit, “Stars and Stripes Forever” making its debut at an 1897 show.

The Manhattan Beach Hotel’s heyday was in the 1880s and 1890s, but it closed by 1911. Already, there were reports of local fishing suffering because of the pollution emanating from this vast complex. After Corbin took over the Long Island Rail Road in 1880, the LIRR set about building the piece de resistance, the Oriental Hotel, located on what is now Oriental Boulevard and Irwin Street. It was constructed in a Moorish style with multiple towers and dozens of balconies and over 400 guest rooms. The magnificent hotel remained open through the 1916 summer season, after which the resort business moved further east, and the hotels would be gone. Corbin built the neighborhood of Manhattan Beach on the landfilled eastern end of Coney Island; it was originally a gated community. Oriental Hotel is remembered by Oriental Boulevard, while the LIRR’s service to Manhattan Beach was terminated in 1924 along with its Bay Ridge Branch passenger service.

During the hotels’ heyday Sheepshead Bay turned to the horses to attract the summer crowds. The Coney Island Jockey Club, Brooklyn’s most magnificent racetrack, opened June 19, 1880 by a consortium of financiers headed by Leonard Jerome, the grandfather of Winston Churchill. A local road that led to the track was named for him, as the Bronx’s much longer Jerome Avenue is. The suburban Handicap and Futurity rcaes were held there until they eventually wound up at Belmont by 1915. The track was also home to Brooklyn’s first mechanized flight, as two dirigibles flew to Brighton Beach. By 1910, flight pioneer Glenn Curtis was flying biplanes from the track, and Calbraith Rogers took off on a transcontinetal flight that took 3 months, a world record at the time.

The former speedway was purchased by another group of developers; this one laid out streets and built one-family homes, calling the area New Flatbush, a name that didn’t stick.

“Never Again”

The center mall at Shore Boulevard, just south of Emmons and Neptune Avenues, is the site of the only memorial park in NYC remembering the Holocaust, in which a government in Germany set about to liquidate an entire race. It was dedicated in 1985.

There is a light and it never goes out.

You who read these words, remember:

Remember that, in the years of darkness from 1933 to 1945, in German-occupied Europe, six million men, women and children were murdered with unprecedented brutality only because they were Jews.

Remember that thousands upon thousands of Jewish communities were uprooted, schools and synagogues destroyed, and the hopes of an entire generations reduced to ashes.

Remember that all this happened at a time when evil was triumphant because the world remained silent.

Elie Wiesel, Survivor

Recipient of the Nobel Prize for Peace, 1986

“Remember”, inscription in the memorial by Elie Wiesel

F. W. I. L.

The Lundy family were fishers and entrepreneurs in Sheepshead Bay as early as the 1880s, with several businesses operating in the Coney Island and Sheepshead Bay area selling shellfish to local hotels (one such business is pictures in the 1920s, above right.) Frederick Lundy Senior began what eventually became one of Brooklyn’s touchstones as a humble clam bar in 1907. It was later expanded on stilts over the bay in the 1920s, but it had to be demolished in the early 30s when the City decided to place a new bulkhead on the south side of Emmons Avenue, replacing the motley arrangement of docks and businesses that had been there (see the photo at top for what it looked like then). (Merlis, Rosenzweig and Miller, Brooklyn’s Gold Coast).

Frederick Sr. son, Frederick William Irving Lundy, recovered magnificently, building the Spanish Mission-style restaurant at Ocean and Emmons Avenues on the bones of what used to be the Bayside Casino in 1934.

From an Amazon review for Lundy’s: Reminiscences and Recipes from Brooklyn’s Legendary Restaurant:

Lundy’s was an immense establishment, seating 2,800 patrons in its heyday, but the enormousness of the space was second to its food. The food was not only excellent, according to nearly every source listed–the portions were in keeping with the grandiose feel of the building itself. Author/historian Robert Cornfield writes, “The oddity is that for all its great size, simple fare, crows, and noise, Lundy’s was not a cold, impersonal restaurant, but was replete with community excitement, curiosity, warmth, and the delirious happiness of a splendid holiday.”

While Lundy’s closed in 1979 the building was never demolished and it was reopened, with about 800 seats, in 1995.

The bridge was lit by mini-versions of the old Belt Parkway “woodie” poles; faux “bishop crook” fixtures were installed in the late 1990s.

Rock me on the water

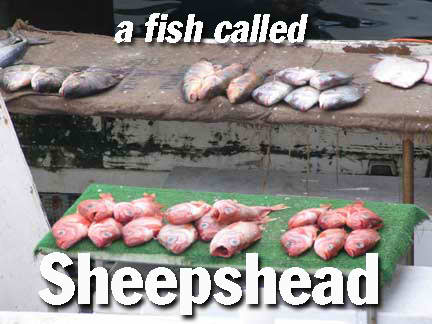

Sheepshead Bay was one of the first fishing ports in the USA catering to party boats; the Bay and nearby Atlantic waters teemed with fish, shellfish and crustaceans. Unfortunately, when housing came to the area beginning in the 1920s, storm sewers were constructed on Ocean Avenue, East 27th and Bragg Streets that emptied directly into the bay, making anything pulled out of the bay inedible. And, when silt piled up on the south shore of Emmons Avenue, additional unsanitary conditions and vermin began to proliferate. This led the City to install a bulkhead in 1937 that streamlined the shoreline and provided the party boats with formal docking areas. In the 1940s about 40 such boats were docked at Emmons, while today there are about a dozen. Weekends still find throngs of fishermen putting out into the Atlantic in search of dinner.

FOR MORE SHEEPSHEAD…SEE PART 2!

Your webmaster Kevin Walsh: erpietri@earthlink.net