Got to admit that I’m a little bit confused…

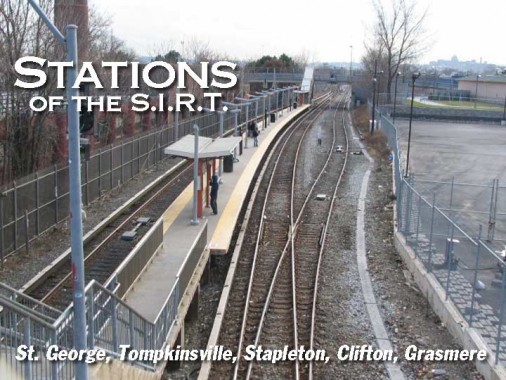

I set out to do a study of the stations of the Staten Island Railway, which I prefer to call its old name, Staten Island Rapid Transit (with 20-minute headways on the weekends, though, it’s not exactly rapid then.) To do this, I set about walking, in four separate trips, the route of the SIRT, and along the way, I saw an opportunity to add to my NEIGHBORHOODS section descriptions of the communities I found in my travels. Thus came the quandary whether to devote different pages to those neighborhoods or simply include them on the stations pages, under the SUBWAYS & TRAINS category. I’ve decided to do the latter, because with time constraints, I do plan to keep the descriptions brief.

I’ve said before in FNY that I’m essentially a small town boy by inclination, despite having lived in NYC for my entire life. I’m in my element when marching through communities in Queens, Brooklyn, Bronx and Staten Island that were once small towns and pointing out the landmarks that make them stand out; Manhattan has largely eliminated its small towns, though there are the odd areas like the Village and Manhattanville that retain a semblance of independence.

For a capsule history of the SIRT (which was once connected to the mainland and operated by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad), see my earlier SIRT page.

WAYFARING: STATEN ISLAND RAILWAY PART 1

There’s been a passenger railroad on Staten Island since 1851 when Cornelius Vanderbilt built a short railroad linking his ferry landing in Clifton to Stapleton. The railroad was extended the following decades to Tottenville, the southernmost point in NY State, to South Beach, and to Cranford Junction in New Jersey (freight only; passenger service ended in Arlington on Staten Island’s north shore). By 1860 the nascent railroad had reached Eltingville, halfway to the island’s southern limit. In 1883, Erastus Wiman, in partnership with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, built a line to South Beach and along the North Shore. By 1885, what would become the SIRT was finished, with the completion of the tunnel between Stapleton and the St. George Ferry. The ferry terminal at St. George opened in 1897. In 1953, service ended on the North Shore and South Beach branches. In 1971, the Baltimore and Ohio sold the SIRT to the New York City for $3,500,001. The SIRT used B&O signalling until recently. Above, view from the Staten Island Ferry to Manhattan, January 2007.

The SIRT has carried some notable passengers. British Prime Minsiter Winston Churchill (whose mother, Jennie, was born in Brooklyn) landed in Tompkinsville (see below) and took a train to a meeting in Washington via the SIRT, traveling through St. George and along the North Shore Branch across the Kill Van Kull to Cranford Junction in New Jersey, and on south. In October 1957, after the North Shore Branch had closed 4 years earlier, a train traveling north from Washington carried Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip to the Staten Island Ferry along the branch for a state visit.

Irvin Leigh and Paul Matus: SIRT: The Essential History

LEFT: The SIRT used BMT-type Standard Steel cars until 1973 when they were repalced by modified R-44 subway cars, brought to the island by truck.

Everything’s Up to Date In Staten Island

It’s odd to say so, but Manhattan’s and Staten Island’s ferry terminals have seen the most progress of any rapid transit facilities in New York City over the past decade. Handsome new terminal buildings have appeared at each landing, carefully constructed around the old buildings, which spared NYers of long periods of demolition and reconstruction. While other mass transit projects like Moynihan Station (Penn Station’s putative replacement), the forever-planned 2nd Avenue Subway, and a rail link from Long Island to downtown have been all talk, no action, decades in the execution, New York can proudly boast that its ferry facilities in 2007 are second to none.

In 1946, the original terminal buildings burned to the ground, and in 1951, its successor was constructed which lasted till 2003, when it was given the major upgrade we have today.

LEFT: ferry entrance in 1953. The nickel fare stood until the 1970s, when it was increased fivefold to a quarter. In the 1990s, the ferry became free of charge, though stiles have been included in the new terminals…just in case.

In the late 1980s, the Manhattan ferry landing burned also, and a temporary shed filled in until a sparkling new building was finished in 2005. By 2003, the Staten Island ferry terminal was in sorry shape: it still wasn’t air conditioned, and pigeons flocked through the expanse, lined with light green, high-school-bathroom tiles.

The new SIR terminal at St. George is handsome and spacious, and allows plenty of natural light. Best of all it allows a generous view of Upper New York Bay, so ferry passengers can view the next boat as it approaches. I thought it was a misprint when I read it, but it’s a good six miles between Manhattan and St. George ferry landings. There are still pigeons about, since the terminal opens to several bus ramps. And why, oh why, are the bathrooms locked on weekends? When riding on weekends you have to seek out the less-than-spotless facilities on the boat. Things are neat and clean here, if a bit…soulless.

Whenever I ride the boat, at least on weekends, I’m just a bit annoyed that I seem to be one of the few non-tourists, and I’m also a little discouraged that most people simply return to the waiting room for the next boat. (New regulations make it mandatory to do so.) Staten Island is NYC too, and deserves better than to be the place in which people wait for the next ferry.

The St. George terminal is one of the very few ferry-bus-railroad intermodal facilites remaining in the United States. The bus ramps remained relatively unchanged during the 2003-2005 station rebuild. An important thing to remember when changing from ferry to bus is to make it quick: there’s only about a five-minute delay between the ferry making the dock and a bus beginning its route, and on weekends, you’ll typically have a 20 to 30 minute wait for the next bus, so best hurry up.

I included a view of the bus ramps from about 1964; here’s a Mack bus, which could be seen on Staten Island streets until 1971 or so, followed by a new GM fishbowl model. Also note the bus ramp light posts: they’re 1930-erafinned Whitestone Bridge-style posts, with gumball luminaires. photo courtesy Tom Mondello, Orchard Inn Reunion

In the 1970s, the whole flock lost their finned masts and gumballs and gained these cobra neck arms and yellow sodium lamps.

It’s unusual to just walk off the bus ramps onto Richmond Terrace, but that’s what I did here. The first thing you see is Staten Island’s impressive Borough Hall, with its elegant clock tower, designed by Carrere and Hastings and completed in 1906. Its main hall displays 12 murals depicting early Staten Island life painted by F.C. Stahr. For more on Borough Hall, see previous link in this paragraph…

If you have some time walk up Hyatt Street, duck into the magnificently restored St. George Theater (which hosted Tony Bennett in 2006), turn right on St. Mark’s Place and wander into a wonderworld of architecture, a few samples of which can be seen here.

St. George, the neighborhood, was named for a land baron named George Law, who had acquired waterfront rights at bargain prices. He agreed to relinquish some of the rights for a ferry terminal – provided it be named for him!

The St. George Terminal platforms, not shown here, are located beneath the bus ramps. Here we see an outbound train heading for Tottenville.

Since 1973 the Staten Island Railway has used modified R-44 units. Before that the SIRT briefly used Long Island Rail Road MP50 push-pull units after the Standard cars were retired! Proof can be seen here.

The only tunnel used for railroad or vehicular traffic in Staten Island is this one, tunneling under what is now planned to be the Staten Island Lighthouse Museum. It was constructed by SIRT builder Erastus Wiman and opened in 1885.

After exiting the tunnel Staten Island Rapid Transit heads for our next station…

Staten Island Railway is free of charge between Tompkinsville and Tottenville: there are no Metrocard turnstiles, and unlike other stations down the line, Tompkinsville has no station house at all. Until July 1997 the MTA collected fares on board, as the conductor would take tickets or cash fares. After the initiation of free subway-bus transfers that month, this practice was ended and realizing that 95% of SIR passengers entered or exited at St. George, maintained stiles and (wo)manned card booths at that station only. As for the other stations, well, the MTA relies on the honor system, although some commuters to Manhattan have for years exited at Tompkinsville and made the 10 minute walk to St. George. Realizing this, the MTA has at times skipped Tompkinsville during morning and evening rush hours and is exploring installing Metrocard booths and stiles here.

Note: given its nearness to St. George, Tompkinsville has added fare collection.

At Tompkinsville the SIR runs in an embankment and the station can be reached by a pedestrian bridge from Victory Boulevard or from a staircase on Hannah Street. In a situation similar to Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City, Victory Boulevard is cut in two by the railroad. Tompkinsville bears center platforms like Stapleton and Grasmere (see below); most SIR stations have side platforms.

On Victory Boulevard just north of the station we find the Joseph H. Lyons Pool, one of eleven city pools built by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses in 1936. The pool was named for a local World War I veteran who was awarded the Croix de Guerre by France, and after the war opened Veterans of Foreign Wars Post #563. Richmond Turnpike was renamed Victory Boulevard at his suggestion.

NYC Parks: The main pool measures 165 feet long and 100 feet wide, while both the wading and diving pools are 100 feet by 68 feet. The pool is designed to accommodate 2,800 bathers at a time; during the first summer, crowds averaged 5,707 people each day. The influence of the WPA pools extended throughout entire communities, attracting aspiring athletes and neighborhood children, and changing the way millions of New Yorkers spent their leisure time.

Moses remains a controversial figure: he eviscerated several NYC neighborhoods –and rarely wealthy ones — to build expressways and parkways. Liked or not, though, he left behind an emerald necklace of parks and twelve great public pools –built, I’ll add, during the Great Depression. It must be noted that Moses himself, while never learning to drive, was an avid swimmer. That means he’s one-upped your webmaster.

Gridskipper has links to information for other NYC great public pools. Only one, in McCarren Park in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, is no longer used as a pool, but has become a top performance and concert space: in 2006 it hosted some of NYC’s premier bands including the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Sonic Youth.

North of the pool Victory Boulevard ends at Murray Hulbert Avenue and the water’s edge. Here we find some woodie lampposts at an old boat landing, and the marvelously Moderne George Cromwell recreation center, with a ship repair facility alongside. It was named for Staten Island’s first borough president after NYC consolidation in 1898.

Murray Hulbert Avenue is likely named for NY Representative George Murray Hulbert (1881-1950) who become commissioner of docks and director of the port of New York City after leaving Congress. During a long illness by Mayor John F. Hylan in 1921, he served as acting mayor.

A walk in Tompkinsville

Before the Revolution Tompkinsville was known as the Duxbury Glebe, a large tract owned by St. Andrews Episcopal Church in Richmondtown that had been bequeathed by Ellis Duxbury in 1718. In 1799 a quarantine station was established here for people with virulent or contagious disease.

Tompkinsville was founded by a future Vice President, NY Governor Daniel D. Tompkins (1774-1825) in 1815. He established a ferry service to Manhattan in 1817, possibly from the landing mentioned above at Victory Boulevard. He was elected Vice President on the ticket with James Monroe in 1816, and served two terms. He died here in Tompkinsville just 3 months after leaving office and is buried in St. Mark’s Churchyard on 2nd Avenue and East 10th Street in Manhattan, and nearby Tompkins Square Park also bears his name, as well as Tompkins Avenues in Staten Island and Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

Daniel Tompkins’ wife, Hannah Minthorne Tompkins, is also remembered by a pair of streets intersecting Bay Street south of Victory Boulevard. His children were named Hannah, Sarah, Griffin and Minthorne.

Victory Boulevard, originally a Native American trail in the pre-colonial era, begins its lengthy journey to the Arthur Kill on the other side of Staten Island here in Tompkinsville. Like Richmond Terrace that runs along the north shore, it was a major coach line for travelers to New Jersey, Philadelphia and points west and south as a ferry carried travelers over the Arthur Kill at the end of the road. Victory Boulevard runs through Tompkinsville, Grymes Hill, Sunnyside, Castleton Corners (Four Corners), Westerleigh, Bulls Head and finally, Travis. The main business district and heart of Tompkinsville can be found along Victory Blvd. between Bay Street and St. Paul’s Avenue.

Tompkinsville Park at Bay Street and Victory Blvd. contains a pair of historic installations: “Hiker,” a Spanish-American War memorial, and a marker commemorating the square’s colonial days.

NYC Parks: The Hiker statue honors those local soldiers who served in the Spanish-American War (1898-1902). Depicting a foot soldier dressed in military fatigues, with a rifle slung over his shoulder, the image (and nickname) is derived from the long marches that the infantry endured in the tropical Cuban climate and terrain.

Several versions of Hiker monuments exist across the country. This one, by Allen G. Newman (1875-1940), was copyrighted by the sculptor in 1904 and for a time served as the official monument of the United Spanish War Veterans (USWV), one of the organizations that that sponsored the Tompkinsville Park monument. One of over twenty Newman Hiker statues cast by J. Williams, Inc., a New York foundry, the pose-the style reminiscent of Newman’s teacher J.Q.A. Ward-is thought to be derived from a famous 1899 image by noted American Western artist Frederic Remington (1861-1909), then a war correspondent in Cuba. Newman Hikers are found in two sizes: a nine-foot heroic version and this seven-foot life-size version.

The statue was dedicated in 1916 and stood in front of Staten Island Borough Hall, but being frequently hit by cars, the stature was moved to its present location in 1925.

Long before Daniel Tompkins made his home here and started a community in 1815, a fresh spring ran through Tompkinsville and here early explorers replenished their water supplies; it was known in colonial times as the “Watering Place.”

The D.A.R. erected this memorial to the Watering Place in 1925, the same year The Hiker was moved here.

St. Mark’s Place, perhaps the street in Staten Island with the most eclectic collection of beautiful architecture, begins opposite Tompkinsville Park on a circuitous route toward the island’s North Shore. Or ends: its house numbers decrease from here. The spire belongs to the 1980s Brighton Heights Reformed Church, which replaced a landmarked structure built 1866 that was destroyed in a fire.

Liggett Rexall Drugs holds down the NW corner of Victory Blvd. and St. Marks Place, with an orange and blue sign that goes back a few decades. Rare in NYC, you can usually find a Rexall in small towns across the USA, like this one in Fargo in the 1920s. There’s another distinctive building on the NE corner. Toward Bay Street, the brick buildings in the row were once covered in ugly blue metallic cladding that was thankfuly removed a few years ago.

Liggett Rexall was founded by Louis Liggett in 1904; its Super Plenamins vitamins were the country’s top seller for several decades. “Rexall” derives from the familar pharmacy abbreviation,”Rx”, plus “all.” The internets have pictures of a lot of extant and defunct Rexall stores and signs around the country in…

Portland, OR; Pleasant Grove, UT; San Francisco, CA; Jellico, TN; East Bradenton, FL; Arnaudville, LA; Hudson Falls, NY; and there’s a lot more, thousands scattered countrywide and in Canada.

At Bay Street and Victory Blvd is a spanking new all-glass NYC bus shelter, still in shrink wrap, along with the only pole-mounted SIR sign I’ve yet seen. Since vandals made quick work of the last batch of glass bus shelters in the 1970s…good luck with that.

The SIR continues on south past the old Staten Island Navy Homeport site (the Navy base was in operation from 1990-1994 and was controversial since vessels carrying nuclear weapons were to dock there, a plan opposed by Mayor Dinkins). NYC has been weighing options on how to redevelop the old Homeport docks for over ten years. A plana few years ago floated by Danny Aiello and others to turn it into a movie studio fell flat.

On October 26th, 2006, the New York City Council finally approved a massive redevelopment plan for the site. It will be transformed into a new community with 350 housing units, restaurants, parks, a recreation center and farmers’ market. Again…good luck with that.

Our next stop is…

At Stapleton the SIR is raised on a concrete viaduct. Most grade crossings on the railroad were eliminated in the 1930s on the North and South Shore and South Beach branches, and you will see the date of construction of the viaducts typically on streets running under them. Stapleton Station can be entered from staircases on Prospect and Water Streets.

In 1836 Minthorne Tompkins (the son of Vice President Daniel Tompkins) and merchant William Staples established a ferry to Manhattan and founded the village at Bay and Water Streets. German immigrants built numerous breweries in the area in the 1800s including Bachmann, Bechtel, and Piels, whose brewery was in business on Staten Island until 1963. The National Football League had a franchise in Staten Island, the Staten Island Stapletons, between 1929 and 1932; they played at Thompson Stadium, which has since been replaced by Stepleton Houses at Tompkins Avenue and Broad Street.

I have already covered Stapleton in my STAPLETON, CLIFTON and ROSEBANK page. I did shoot several new photos while exploring today, though…

While most of Stapleton’s stock of 19th-Century houses– some of them the most impressive buildings in the Northeast — can be seen on St. Paul’s Avenue (some of which were covered in ForgottenTour 16) there are a few hidden superannuated buildings, some of which go back to the mid-19th Century here n Bay Street and its tributaries, Baltic and Clinton Streets. A sloped hill gradually rises to the edge of Grymes Hill, where lurk immense (and immensely expensive) mansions.

The Paramount, at 560 Bay Street near Prospect, is now likely Staten Island’s premier ‘ghost theater’ now that the St. George has been reactivated as a performance venue. It was designed by architects Rapp and Rapp with a contrasting orange brick façade, opening in 1935 with a capacity of 2500 seats and two pipe organs, an extravagant feature during the Depression. It closed in the early 1980s and has been left as is ever since.

Railroad and shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt grew up on a farm here in his boyhood; he had been born in Port Richmond.

Masonic Hall turned post office, Bay Street

Tappen Park, between Bay, Wright, Water and Canal Streets. Stapleton was once a part of the village of Edgewater, and its old Town Hall is visible in the distance.

Clifton is the last SIR station located along Upper New York Bay just east of Bay Street. Here, the SIR turns south and west along a right of way somewhat inland from Staten Island’s South Shore on its way to Tottenville. However, until 1953 the South Beach Branch served Rosebank, Arrochar and South Beach with stops at Rosebank, Belair Road, Fort Wadsworth, Arrochar, Cedar Avenue, South Beach and Wentworth Avenue. The latter was a ten-foot platform, just enough room for one door to open. The South Beach and North Shore branches usually ran one-car consists. The South Beach Branch split from the main line just south of Clifton station and ran pretty much through backyards along its own right of way on a trestle built in the 1930s. The SIR went through great expense to elevate much of its trackwork in the 1930s–only to abandon two branches less than 20 years later.

When I first began FNY in the late 1990s there were many more traces of the South Beach Branch (visible on my earlier SIR page) than there are today. Only a concrete embankment stanchion on St. John’s Avenue here, an iron trestle on Robin Road there, serve to remind us that the SIR once ran to South Beach. It’s truly a lost railroad; houses have now been built on its right of way.

South Beach once had a large amusement area on Sand Lane near the beach. The last remnant of it disappeared in 2006, a full 53 years after the last train brought beachgoers to the area. South is still a fairly popular beach in the summer, with the state’s third-longest boardwalk (after Ocean Promenade in Rockaway and the Riegelmann Boardwalk in Coney Island), named for Franklin Roosevelt, but it has a certain forlorn quality. Or maybe I just haven’t visited in the summer yet.

Clifton is the first station on the SIR to feature the renovations that were made to most of the system’s stations in the late 1980s and early 1990s; the stations hadn’t received much TLC since most of them were elevated or placed in open cuts in the 1930s. Railings, lighting and signage were all redone; in some cases, station signage consisted of the names stenciled on wooden planks. The most distinctive feature of the renovations is the use of opaque glass blocks that the graffitists and scratchiters have a lot of trouble with.

Clifton is accessible from the ramp you see above on Bay Street just east of Vanderbilt Avenue.

Clifton, named most likely for its location east of the Grymes Hill cliffs, originally also comprised the adjacent neighborhood of Rosebank.

Clifton’s most distinctive feature is the presence of an old brick shelter on the Tottenville-bound side that was allowed to remain during station renovations. Its Bay Street facing windows have been bricked up, but there’s still one open on the north end. Of course its original glass has disappeared long, long ago.

A small piece of the original station railing can be seen near the entrance-exit on the north end of the Manhattan-bound platform.

Sometime before 1971 (when the Standards were retired) a Tottenville-bound pulls into Clifton. We see the old brick tower that controlled Tottenville and South Beach bound trains, and, of course, our brick shelter. The tower lasted till the 1980s, long after the South Beach branch. Harold Smith, NY Transit Memories

Most of the SIR car fleet maintenance is performed at the Clifton Car Shop located to the north of the station, though motors and wheel/axle work are sent to the larger Coney Island Yards. NYCSubway has more pictures, past and present, of the Car Shop here.

A Tottenville-bound train is approaching Clifton. Grymes Hill looms in the background.

Clifton was incorporated as a village in 1817. Bayley-Seton Hospital, between Bay Street and Tompkins and Vanderbilt Hospitals, dates to 1831 when the Seaman’s Retreat was built as the first NYC hospital devoted to the care of retired sailors (it is not to be confused with Sailors Snug Harbor, which originated in Greenwich Village). The institution would continue with its original purpose for 150 years; and the usefulness of penicillin in treating venereal disease was verified here. It was renamed for Dr. Richard Bayley, first Health Officer of the Port of New York, and his daughter Elizabeth Bayley Seton, founder of the Sisters of Charity and first American-born saint (canonized 1975). More recently, popular rap stars Wu-Tang Clan hailed from Clifton.

710 Bay was built in 1848 for Dr. James Boardman, resident physician at Seaman’s Retreat, now the adjoining Bayley-Seton Hospital. In 1894 the house was sold to Captain Elvin Mitchell, whose daughter, a NY State beauty contest winner, lived in the house until 1966.

Eibs Pond, one of Staten Island’s many “pocket ponds,” is located in Fox Hills just to Clifton’s south. Nearby streets are named for European rivers. I’ll do an item on Fox Hills, one of the isalnd’s truly unknown areas beyond its residents, on an upcoming page.

Vandy-land

Along Vanderbilt Avenue between Talbot Place and Tompkins Avenue you will see a series of phantasmagorical British-style cottages, like something from a movie set. Incredibly aged London plane trees line the sidewalks in front of them.

This is a remnant of a residential complex built for Vanderbilt scion George in 1900 by Carrere and Hastings. Other houses were built for the Vanderbilts on neighboring Norwood Avenue; additional mansions were found on nearby Townsend Avenue, but many of them have been lost to redevelopment, and this is not a landmarked area.

Needless to say the new houses rising in place of the older stock in the area, to put it politely, are not in their caliber.

Before we get too depressed about NYC’s ongoing inferior renewal, let us press on to the next station. It’ll require a lengthy walk, going out of our way (see Wayfaring above) because inexplicably, there’s a gap of almost one mile between Clifton and Grasmere.

Mere Grass

Grasmere is the last center-platformed station until Bay Terrace, and is located in a very suburban area pockmarked by small lakes like Brady’s Pond and Cameron Pond (both featured on this FNY page). Grasmere boasts its 1933-vintage brick stationhouse, which even has now-verdigris’ed lettering above the entrance arch. It’s on Clove Road, a bit west of the most important nearest intersection at West Fingerboard Road.

Grasmere figured peripherally in my career at the now-defunct Center For the Media Arts, where I picked up computer programs like Quark XPress in 1990-1992 and led to my website and sort-of bestselling books. Anyhow, the school was located at 7th Avenue and West 26th Street and, especially on weekends, I’d look for a change of pace to get home to Bay Ridge, which is where I lived before moving to Flushing. So: I’d take the #1 train from 28th Street to South Ferry, take the ferry to St. George, then the SIR to Grasmere, switch to the S-53 bus, which crossed the Verrazano Bridge to Bay Ridge and I was home. Took me about 1 and 1.2 hours, about a half hour more than it would if I just took the subway home. More expensive too, these were the days before free bus-subway transfers.

In the 1800s, a Britisher, Sir Roderick Cameron, built a mansion in the area near the present intersection of W. Fingerboard Road and Steuben Street. The mansion’s gatehouse is supposedly still there. Cameron is remembered by Cameron Lake and nearby Roderick and Cameron Avenues.

This photo of Grasmere Station by Doug Grotjahn (from the massive NYCSubway collection) shows the condition Staten Island Rapid Transit was in the 1970s and well into the 1980s. The rusted Standard Steel cars were soon to be replaced by new R-44 cars (still used today) but the tracks are trash-strewn, the canopy shelter is rusting, and the station house windows are broken. If there are any lights, they are incandescents under the canopy. It wasn’t till the mid to late 1980s that the MTA began to take back the system from vandals and graffitists.

In the 1980s, new canopies were added to the 1930s-era staircases.

Grade crossings were eliminated in Grasmere, Old Town, and Jefferson Avenue from 1933-1935.

Platform lighting in the SIR is unique in the Metropolitan Transit Authority–this style is not found on the subways, LIRR or Metro North.

These lamps replaced goose-necked incandescents used on side platforms.

RIGHT: The signature SIR glass blocks, reflecting the setting sun.

Next time: Old Town, Dongan Hills, Grant City, New Dorp and Oakwood Heights

Page photographed January 8, 2007; completed January 21