As much as any other neighborhood in Brooklyn, Windsor Terrace’s boundaries are rather easily defined: it’s that narrow strip, about 8 or 9 blocks at the widest, between the vast greenswards of Green-Wood Cemetery and Prospect Park. Prospect Park West (which 9th Avenue is inexplicably called here — the stretch doesn’t border the park) is its northern boundary with Fort Hamilton Parkway the southern. Originally Windsor Terrace proper extended from Vanderbilt Street south to Ft. Hamilton Parkway and was a northern extension of the town of Flatbush, but after Flatbush was annexed by Brooklyn in 1894, and Brooklyn was then consolidated with NYC in 1898, just about all the territory “between the green” is included.

The neighborhood, named for Windsor, England, was first built up by developer William Bell between 1849 and 1851 between Vanderbilt Street and Greenwood Avenue, and row houses sprang up on 16th Street and Prospect Park Southwest by 1905. Windsor Terrace was heavily Irish in the early 20th Century, and remains a quiet, relatively undiscovered neighborhood despite the construction of the Prospect Expressway from 1953-60; thankfully, a proposal to extend the expressway south along Ocean Parkway — which would have become a 6-lane expressway–was never acted upon.

Windsor Terrace begins, and Park Slope ends, at Bartel-Pritchard “Square,” on 15th Street, one of three traffic circles, or roundabouts as they say in England, surrounding Prospect Park. The square was named for Emil Bartel and William Pritchard, two young Brooklyn natives who were killed in combat in World War I. Its most striking feature, perhaps, is the curved contours of the brick buildings surrounding it.

The 9-screen Pavilion opened in 1996, when I saw Independence Day there (“now that’s what I call a close encounter” says Will Smith’s character). However, the building is much older: This theatre dates back to 1908, when the brothers Harry & Rudolph Sanders opened a nickelodeon called the Marathon on the site. Rapidly expanding into adjacent storefronts, the Marathon developed into a theatre of 500 seats. In 1928, the owners replaced the Marathon with the entirely new and self-named Sanders Theatre, tripling their seating capacity to 1,581.

When the Sanders finally closed in 1978, plans to convert it into retail or residential space never bore fruit. In 1993, exhibitor Norman Adie and three local investors bought the property. In 1996, they re-opened it as the Pavilion Theatre with three screens. Five more have been added since. cinematreasures

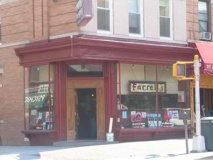

Some say that Windsor Terrace begins at Farrell’s, the venerable (1933) institution at Prospect Park West and 16th Street, where, despite the neon sign, there hasn’t been a grill for years, though you can get corned beef sandwiches on St. Patrick’s Day. There’s no table service at all–you drink at the bar. If you were female, you didn’t drink at the bar until 1972, when Shirley MacLaine swept in with her then-boyfriend, Park Slope’s Pete Hamill, and demanded service, ending the outdated tradition.

Holy Name of Jesus Church, Prospect Park West and Prospect Avenue

The parish led the unsuccessful effort to prevent or reroute the Prospect Expressway in the 1950s.

Green-Wood Cemetery entrance, Prospect Park West and 20th Street. This entrance is not always open.

McDonald (formerly Gravesend) Avenue begins its lengthy journey to Coney Island at 10th Avenue and 20th Street, a corner distinguished by the Bishop Ford Central Catholic High School radio tower.

The high school was opened in 1962 and remembers Father Francis X. Ford, a missionary killed in China in 1953. The school itself incorporates a rough pagoda design.

Our building, located in the Park Slope area at 500 19th Street, occupies the site of the old Brooklyn trolley barns, on which, during the Civil War, stood a Federal prison. bishopfordhs.org

Prospect Expressway, built between 1953 and 1960, runs between the Gowanus Expressway and Church Avenue, where it ends rather abruptly at Ocean Parkway. The original parkway was completed between 1874 and 1880 and was designed by Prospect and Central Park masterminds Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. The parkway serves as a service road for the Prospect Expressway from Park Circle to Church Avenue; it’s doubtful that Calvert and Vaux’ work would be so compromised were the expressway to be built today.

Fencing has been installed at the 10th Avenue pedestrian crossover, to prevent anyone from throwing objects onto traffic. Seen from here, it reveals an interesting pattern.

Most street maps show Prospect Avenue intersecting with Seeley Street, but it never has.

The glacial moraine running through mid-Brooklyn produces some steep hills. When Prospect Avenue and Seeley Street were laid out through the area many decades ago it was considered prudent to bridge Seeley over Prospect. Such traffic bridges occur more frequently in the Bronx, which has some steep scarps, but are quite rare in Brooklyn.

Vanderbilt Street, named for mid18th-Century Flatbush jurist John Vanderbilt, contains some examples of Windsor Terrace’s unusual building types (see Greenwood Avenue below for more striking examples).

Vanderbilt Street also marks the dividing line between Brooklyn’s two most extensive street numbering systems, the western Brooklyn system that runs from Park Slope to Bay Ridge (1-101) and the East streets that dominate southern and eastern Brooklyn (East 1-East 108th).

A block south of Vanderbilt, Greenwood Avenue (named for the cemetery but without the hyphen) contains unsual examples of 19th Century architecture that may go all the way back to the neighborhood’s beginnings, including the rustic Church of the Holy Apostles.

More unusual houses, East 5th Street facing the expressway.

The Romanesque Revival Engine Co. 240 was built at 1309 Prospect Avenue in 1896. It contains a lookout tower dating to the era that preceded fire alarms.

Fort Hamilton Parkway, despite its name, is a major truck route as it pierces the strict grid in Borough Park, Dyker Heights and Bay Ridge. Between Ocean Parkway and Green-Wood Cemetery it’s lined with several fine brick apartment buildings.

Kermit Place, a narrow lane between Ocean Parkway and Coney Island Avenue north of Caton Avenue, was named before the suicide of Theodore Roosevelt’s son Kermit in 1943, but perhaps it had been influenced by the renaming of Avenue Q for his brother, Quentin Roosevelt, who died on a flying mission in World War I. Maps show Kermit Place’s former name as Henry Street.

The Calvary Cathedral of Praise, Caton Place and East 8th Street, is a new state of the art house of worship. Top names in gospel music, including CeCe Winans, have appeared there.

Are those people on horseback there?

Kensington Stables, Caton Place and East 8th Street, is the last remaining Prospect Park stable, serving its bridle path, and is one of the last two stables remaining in Brooklyn (the other one is the Jamaica Bay Riding Academy on Shore Parkway east of Flatbush Avenue). The barn goes back to 1930.

Kensington Stables, at Caton Place and East Eighth Street, is the last stable remaining at an intersection that was once home to several such enterprises. In their heyday, at the beginning of the 20th century, hundreds of horses were stabled there. But the Depression and the automobile transformed horseback riding from a necessity into a hobby, one soon overtaken by other leisure activities.

No one remembers exactly when the changes started to take place — around the 1930’s or 40’s, old-timers suggest. The first stable to disappear was converted into a roller-skating rink, which later became a warehouse. The second was converted into a bowling alley, which later gave way to a giant church, the Calvary Cathedral of Praise. A third stable, known as the Little Gray Barn, was torn down [in 2003] and is being replaced by condominiums. village voice