Before the 1820s or so, New York City was pretty much confined to the area south of City Hall and indeed, City Hall was left unfinished on its north side since no one believed the city would ever extend north of that. Manhattan Island was dotted with hamlets and small villages, connected by roads like the Eastern Post Road (or Boston Post Road) part of which became Park Row and the Bowery, and Bloomingdale Road–that became Broadway.

In July 2006 and May 2007 I stalked around one of these small towns–Manhattanville, which now is incorporated as a New York City neighborhood and runs between about W. 123rd Street on the south, W.135th on the north, the Hudson River on the west and the City College of New York on the east–in search of some of its small-town and suburban past. The area was ripe for the plucking.

Of all of Manhattan’s former self-contained villages, such as Harsenville, Yorkville and Seneca Village, Manhattanville has retained more of a singular identity than the others. Indeed, its old street pattern, centered on slanting West 125th (formerly Manhattan) Street, predating the overall street grid, has been retained. The village was founded in 1806 in a deep valley whose location was propitious for cross-island travel to and from the older village of Harlem to the east.

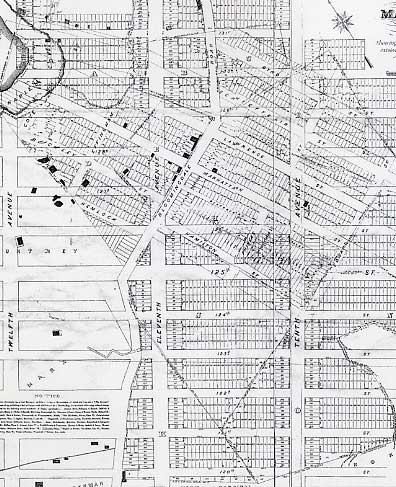

This map, drawn in 1878, shows Manhattanville’s street layout which ran askew of the Commissioners’ Plan grid pattern that was drawn up by surveyor John Randel Jr., instituting the island’s street grid system, approved in 1811. Since then the city had gradually spread uptown, laying out streets, leveling hills, filling in ponds. Some small towns, like Yorktown and Harsenville, left no discernible trace of their old layouts — the grid pattern absorbed them. Others, like Seneca Village, were swallowed by Central Park. map: Manhattanville, Old Heart of West Harlem, Eric K. Washington, Arcadia 2002

Manhattanville, though, was a bit different, and like Greenwich Village, it more or less defied the Commissioners Plan and in some cases, maintained its old street layout. Over the decades a good deal of it has been erased. But two of the main streets retain their old routes: check the map for Manhattan and Lawrence Streets. Both are still where they always were. The bend West 125th Street (Dr. Martin Luther King Blvd.) takes west of Morningside Avenue is the point where Manhattan Street began; likewise its partner to the north, Lawrence Street, now West 126th. Manhattan Street was renamed West 125th in 1920, and the old route of West 125th west of Morningside Avenue became LaSalle Street (for Jean Baptiste de la Salle, a founder of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, an order that founded Manhattan College which has since moved to Riverdale in the Bronx).

Also note Bloomingdale Road on the map: it has been straightened and is now Broadway, but we’ll get back to that later.

WAYFARING: Morningside Park-Manhattanville (open in separate window)

I began my search for Manhattanville remnants on Amsterdam Avenue and West 122nd, where you will find the Clinton Supply Co. at 1256 Amsterdam. Clinton Hardware has been in business since about 1950, first at 1262. Nearby Aris Beauty Salon has been there even longer, since 1933. photo: Manhattanville, Old Heart of West Harlem, Eric K. Washington, Arcadia 2002

General Grant Houses, a large project south of West 125th Street between Broadway and Morningside Avenue, consists of nine buildings, 13 and 21 stories tall with 1,940 apartments providing housing to over 1400 families. The complex, with the adjacent Morningside Houses, was completed in 1957, along with your webmaster.

A view of West 123rd, one of just a handful of east-west streets, along with West 125th, 126th and 127th, to link Manhattanville and Harlem. We are looking west toward Grant’s Tomb in 2007 and in 1900.

West 123rd is the site of a massive glacial rock outcropping; these occur frequently in northern Manhattan and in the Bronx. A defense fortification, Blockhouse No. 4, was built here in 1812 when it appeared that the British would attack New York City, having sacked and burned Washington, DC. The British, however, got no closer than Stonington, CT during the War of 1812. This blockhouse was torn down decades ago; however, one has been preserved in Central Park.

The outcropping, however, remains and in one of NYC’s more impressive engineering marvels, PS 36 was built on it in 1967; you can see some of it in the 2007 photo. photos: Manhattanville, Old Heart of West Harlem, Eric K. Washington, Arcadia 2002

It’s a Beautiful Morningside

If you look at the map, 30-acre Morningside Park can be seen as a northern fingerlike extension of Central Park, extending as it does from Cathedral Parkway (West 110th Street) to West 123rd Street roughly between Manhattan and Morningside Avenues and Morningside Drive. And, it was designed by Central Park architects Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, opening in 1887; Jacob Wrey Mould, who designed the carvings at Bethesda Terrace in Central Park, finished Olmsted and Vaux’ plan and designed the masonry wall along Morningside Drive. Located along a steep cliff, the park takes its name from the morning sun that illuminates the cliffs.

The park’s design continued to evolve in the 20th century. Monuments installed in and around the park included Lafayette and Washington (1900) by Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi (left), the Carl Schurz Memorial (1913) by Karl Bitter and Henry Bacon, and the Seligman (Bear and Faun) Fountain (1914) by Edgar Walter. Between the 1930s and the 1950s playgrounds, basketball courts, and softball diamonds were constructed in the east and south parts of Morningside Park. NYC Parks Department

At Morningside Avenue and West 120th Street we see a mural honoring PS180, the Hugo Newman School, featuring local landmarks.

We’re really in Western Harlem here (an area I’ll explore in depth on a future page), on Manhattan Avenue between West 113th and West 123rd Streets. It’s a quiet stretch with several examples of brownstone buildings. The lampposts are being converted to retro-Corvingtons, with some bizarre hybrid posts.

At a confluence of roads (West 124th Street, Manhattan and St. Nicholas Avenues, and Hancock Place) we find a bust of Winfield Scott Hancock by James Wilson Alexander McDonald, dedicated in 1891. Hancock (1824-1886) served with distinction for the US Army in both the Mexican and War Between the States. Perhaps his greatest triumph came at Gettysburg:

On July 3, Hancock continued in his position on Cemetery Ridge and thus bore the brunt of Pickett’s Charge. During the massive Confederate artillery bombardment that preceded the infantry assault, Hancock was prominent on horseback in reviewing and encouraging his troops. When one of his subordinates protested, “General, the corps commander ought not to risk his life that way,” Hancock is said to have replied, “There are times when a corps commander’s life does not count.” During the infantry assault, his old friend, now Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead, leading a brigade in Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division, was wounded and died two days later. Hancock could not meet with his friend because he had just been wounded himself, a severe injury caused by a bullet striking the pommel of his saddle, entering his inner right thigh along with wood fragments and a large bent nail.

Helped from his horse by aides, and with a tourniquet applied to stanch the bleeding, he removed the saddle nail himself and, mistaking its source, remarked wryly, “They must be hard up for ammunition when they throw such shot as that.” News of Armistead’s mortal wounding was brought to Hancock by a member of his staff, Captain Henry H. Bingham. Despite his pain, Hancock refused evacuation to the rear until the battle was resolved. He had been an inspiration for his troops throughout the three-day battle. Hancock later received the thanks of the U.S. Congress for “… his gallant, meritorious and conspicuous share in that great and decisive victory.”wikipedia

Hancock was named for General Winfield Scott (1786-1866). A Democrat, he lost by the narrow margin of 7,000 votes to James Garfield for the presidency in 1880. Memorial statues to the general can also be found in Market Square (Pennsylvania Ave. and 7th Street) in Washington, DC, in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, and Cemetery Hill at Gettysburg, PA.

St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church at Morningside Avenue and West 125th was constructed in 1860. It was the scene of NYC’s first Corpus Christi procession in 1861.

The bend that West 125th Street takes west of Morningside is marked by a decades-old yellow signal light. Note that the detail marks it to be pretty much the same genus and species of NYC’s old Olive stoplights.

West 126th (Lawrence) Street between Morningside and Amsterdam Avenues. The bend in the street marks the break between Manhattanville’s old street pattern and the new Commissioners’ Plan grid. A notch in an old building along West 126th may, or may not, mark the cross of one of Manhattanville’s now-vanished streets.

The old Bernheimer and Schwartz Pilsner Brewing Companybuilding, at the corner of West 126th and Amsterdam Avenue, built in 1905, has undergone a couple of renaissances since the hops hopped out. For over 50 years it was a fur storage center; now, as The Mink Building, it is a 137,000 square-foot mixed use facility, consisting of loft-type office space and light industrial, warehouse and retail space.

The Speyer School was built as a school by philanthopist James Speyer in 1902 in a Flemish Renaissance style. In 1964 St. Mary’s Church (see below) purchased the building; now it is used as an AIDS hospice.

The Episcopal St. Mary’s Church is in many ways the heart of Manhattanville. It was first organized in 1823 as a branch church of the affluent St. Michael’s in the town of Bloomingdale to the southwest. St. Mary’s first church building was here on West 126th west of Amsterdam from 1824 to shortly after 1900.

It’s a difficult concept to consider these days but from the colonial era to the mid-1800s, most churches charged pew rentals, ie. you paid to pray. St. Mary’s was the first church in the city to abolish pew rentals in 1831.

The present church was built in 1909 by the renowned NYC architects Carrere and Hastings and T. E. Blake.

St. Mary’s parsonage, built in 1853, still stands behind the church. In an alcove near St. Mary’s front door is a vault containing the remains of Jacob Schieffelin (1757-1835) and his wife, Hannah Lawrence Schieffelin (1758-1840).

Jacob Schieffelin, a Tory during the Revolutionary War, volunteered for the British and was captured at the Battle of Vincennes in 1779, but escaped to British-held New York in 1780, where he met and married Hannah Lawrence; he was with a British outfit occupying the Lawrence home. They spent the remainder of the war in Montreal but returned to NYC in the 1790s. In 1824, the couple donated a lot in Manhattanville where St. Mary’s Church was built, and the two were buried in a vault here after their deaths.

Questions: what nation or organization does this flag represent, and what is the English translation for the banner in Spanish? Both appear outside St. Mary’s.

Forgotten fans are always ready! Patricia Coate says:

The flag in question is that of the Episcopal Church of the United States of America (not Anglican, btw). You can see St. George’s cross. The little St. Andrew’s cross in the corner is supposed to represent its roots in Scottish Episcopalianism.

The Spanish banner says:

“St. Mary’s Manhattanville is the church “without fear,” looking for peace and justice alongside the poor and oppressed, speaking for and taking care of the sick, alone, and marginalized, and practicing the message of the Gospel with the force of the Holy Spirit.” Luke 1:30

Next door to St. Mary’s parsonage is Sheltering Arms Playground, occupying the spot on West 126th (Lawrence) Street where the Sheltering Arms Asylum was built in 1870, a haven for homeless, abandoned and ill children, founded on West 100th Street by Rev. Thomas Peters in 1864. The straightening of Bloomingdale Road (which became The Boulevard and later, Broadway) forced the asylum to move here.

In 1944, the Sheltering Arms merged with the New York Children’s Foster Home Service to create the Sheltering Arms Children’s Service, whose headquarters today are located on East 29th Street. Parks acquired the land from the Sheltering Arms under Robert Moses (Commissioner from 1934-1960) during the administration of Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia. NYC Parks

Why is there an Old Broadway in Manhattanville? Isn’t Broadway itself pretty old?

Very. It follows the path of a trail known in colonial days as Bloomingdale Road, which started at about where Madison Square is now, at 5th and 23rd (before these streets were mapped or cut through of course) continuing along the present path of Broadway to 86th Street, where it veered east, running between today’s Broadway and Amsterdam Aves. At 104th St it again assumed Broadway’s present route until 107th, where it turned northwest until meeting the present path of Riverside Drive, following it to 116th. Here it turned northeast again, crossing Manhattan Street (today’s 125th Street) as Old Broadway. From 133rd Street it ran slightly east of the present Broadway to Amsterdam and 144th Street (today’s Hamilton Place is another remnant) and ended at St. Nicholas Avenue and 147th Street.

As the area became more populated, and Bloomingdale Road was straightened and widened into the Broadway we know and love today in the 1870s, a bend in the road between 125th Street and 133rd Street was left over…which became Old Broadway.

In the 1960s, Old Broadway was separated into two pieces by the Manhattanville Houses. The ForgottenBook

The most significant structure on Old Broadway is the smallest one, Old Broadway Synagogue, incorporated in 1911. The present building dates to 1923. Amazingly, it is the only synagogue in Manhattanville or Harlem, to boot. Jewish populations held firm in Manhattanville decades after they had abandoned Harlem.

Vestiges of Harlem’s Jewish Past [NY Times]

Manhattan Valley

Manhattan Valley runs from Broadway to the Hudson between Columbia University and about West 135th Street. Around the turn of the 20th Century engineers were faced with two vexing problems as they extended he brand-new subway system as well as Riverside Drive through the valley: do you tunnel deeper under the valley, or simply bridge over it? The builders of both projects chose the latter…and we have two magnificent, iconic structures as a result of the decision.

Though the IRT bridges West 125th Street spectacularly, subway designers Heins and LaFarge also took care to place decorative elements in wrought stonework beside the simpler trestles that take the tracks over parallel streets, like LaSalle Street.

Archstone

The Archstone, 45 Tiemann, is a worthy successor, boasts clever and tasteful terra cotta ornamentation.

A Puzzlement

Sign with no street. Moylan Place is marked on the right side of Broadway just south of West 125th, but there’s no street to be found. 1930s maps and street guides show a Moylan Place running from Broadway to Amsterdam here. The General Grant Houses occupy the space now as they have since 1957.

My guess? Perhaps some houses in the Grant project have a Moylan Place address. Anyone know?

Note Geographia Manhattan street directory, 1930s.

Back to West 125th between Broadway and Riverside Drive. There’s the Eritrean Community Center, what appears to be either and old theater or a gradiosely-designed garage, and the meeting of 125th and 129th Streets, due to Manhattanville’s odd street layout.

Forgotten Fan John Albin: Actually, it’s a former dairy (I think it was “Sheffield Farms, or something along those lines; there used to be a sign on the facade). When I attended Columbia in the early 80s, it was owned by Columbia and called Prentiss Hall. IIRC, it went through several incarnations with Columbia (labs, shops, etc). When I was in school it was the headquarters of Columbia’s fine arts grad school and various music and art studio facilities. I’m not sure if Columbia still owns it.

Eritrea is a small country on Africa’s east coast, a former Italian colony on the Red Sea bordering Sudan, Ethiopia (with which it fought a border war from 1998-2000) and Djibouti.

This was part of an early 20th-Century dairy district. ForgottenFan Joe Brennan: Prentiss is still a Columbia building, and like Studebaker [see below] it will remain with interior renovations. Buildings on some of the other blocks will be torn down and replaced with new larger structures. Whatever milk company it was, this was where milk in large metal containers from the farms was repackaged into those waxy containers it was sold in. I was in there in the mid 1970s and it still smelled like an old milk carton!

NYTimes, January 13, 2007: …This was designed by Frank A. Rooke — a specialist in stable and industrial architecture — with a pure, gleaming front of white glazed tile, and trimmed with copper windows and other details, oxidized to green.

The Sheffield dairy had a copper and glass overhang over the central section, shielding delivery wagons from the elements. The milk cans were emptied on the top floor in a dust-free room: the windows were double-glazed, and air pressure was kept higher than that outside, so air was constantly flowing out.

Inside, the walls were pure white-painted plaster, meeting in curves to avoid dirt-catching corners. The ceilings were a green glass tile, ribbed and translucent. Milk flowed down through filters and pasteurizing equipment until bottled and sealed at the ground-floor level. Ice was dumped into the screen-bottom milk crates, which were transferred to delivery wagons moving through a half-oval path on the interior, entering on the right side of the building and exiting on the left.

The new plant could process and pasteurize 15,000 bottles an hour and, according to a 1911 article in the magazine Architecture and Building, was the brainchild of Loton Horton, head of Sheffield, “whose long life has been devoted to the study of pure milk.”

Mr. Horton had bitterly opposed the 1912 city law that required all milk to be pasteurized, but nevertheless designed his plant with pasteurizing capacity.

The present incarnation of The Cotton Club is in the triangle formed by West 125th, St. Clair Place, and Riverside Drive. The original, opened by famed boxer Jack Johnson in 1920 as the Club DeLux, was situated at Lenox Avenue and West 142nd Street; it was renamed by new owner, gangster Owney Madden, in 1923. The club helped launch the careers ofFletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and many other jazz and pop stars of the 20s and 30s. The original Cotton Club closed in 1936, with a second incarnation at Broadway and West 48th Street from 1938-1940. A new Cotton Club reopened at its present location in 1978 and is presently owned and operated by John Beatty.

St. Clair Place is named for St. Clair Pollock, who is buried near Grant’s Tomb.

Magnificence

The Riverside Drive viaduct was constructed in 1900 to take the Drive over Manhattan Valley. The metal arch spanning West 125th Street measures 130 feet in width. Looking down 12th Avenue (the avenue was “reactivated” here for the road under the viaduct; the southern part of 12th Avenue ends at West 59th Street) the metal arches seem to stretch into infinity. The view has been used in dozens of motion pictures and commercials.

The beauty of the viaduct lies in its timelessness. 1900 was at the peak, or just past the peak, of the Beaux-Arts architectural era when no ornament or gewgaw on a building was too much. The architect (who I don’t yet know the identity of) was spare in his approach. Only on the Riverside Drive surface roadway was there any ostentaneousness, with ornate fences, benches and lamps, long since disappeared.

The viaduct’s arches not only seem to go on forever, they appear as if they will. In NYC lately, nothing goes on forever.

Directly under the Viaduct at West 125th we have a remnant of Manhattan’s trolley system, which was unique in that the trolleys didn’t take power from overhead wires, which were illegal in Manhattan. In Manhattan local laws prohibited unsightly overhead trolley wires, and so street railways had to take power from electric conduits located beneath the pavement. Streetcars had a thin arm, called a plough, that extended into a below-pavement channel containing a charged rail with up to 600 volts (the same juice that subway third rails of today carry). The rail was placed between the two rails that carried the wheels.

An extra track, the conduit slot, is in the middle, marked “3 Ave” in spots. Some surface lines in NYC became a part of the Third Avenue Railroad System and so some of the insulator and manhole covers carry the name “Third Avenue.”

[By 2012, I hear, these remnants had been paved over or removed as part of Columbia U. construction]

12th Avenue under the Viaduct remains a large meat processing and wholesaling area with even some poultry slaughterhouses scattered around. The raw meat aroma permeates the air under the Viaduct and, perhaps, intoDinosaur Bar-B-Que on 12th and West 131st.

West 125th ends at the Hudson River after running under yet two more overpasses belonging to the Metro-North Hudson River RR and the Henry Hudson Parkway. Along what maps call “Marginal Street” is the exit ramp from the large Fairway Supermarket that faces the water.

True to form I was more interested in the remaining 1940s-era Westinghouse “cuplights” found under the Henry Hudson overpass.

West 131st between Broadway and the Viaduct is dominated by a large former Studebaker factory. Before Studebaker occupied the building it was a Borden’s milk processing plant (see above NYTimes link).

Forgotten Fan Jan Young writes: What streetlamps are to you, Studebakers are to me. I’ve spent a lot of time studying the company’s history and even own a working Studebaker automobile. So naturally your mention of the Studebaker building in Manhattanville caught my attention. I had been aware of the building, but hadn’t seen photos of it. It appears in much better condition than I would have imagined. Thanks for including it on your page.

Your description of Studebaker on this page is accurate. However, calling the Manhattanville building a factory isn’t. It was, instead, a distributorship. Studebakers were made in South Bend, Indiana and in Detroit (depending on the year) and were shipped to a number of distributors around the country where they were stored and eventually shipped to individual dealers. The Manhattanville building doubtlessly includes (or included) a number of large freight elevators for moving cars from floor to floor and I suspect that the tower housed elevator machinery, maybe in addition to other things. In addition to the car storage areas, the building almost certainly included regional sales offices, an extensive parts warehouse, and dealer/mechanic training facilities.

Out of curiosity, do you have any resources that cite the date this building was built? Based on my knowledge of company history, I’d guess the early 1920s, but I’m not an architect and it could be older than that — or maybe a little younger. The “wheel” logo that appears on the building was largely phased out in the early 1930s, but the latest possible date for the building is probably earlier than that because the company ran into financial troubles starting in 1931 and its days of building construction were over until WWII came along.

ForgottenFan Joe Brennan: A step inside will show in the lobby an original plan which [dates] to the 1920s as someone speculated. The exterior has been restored in the past two years by Columbia. The original windows were all replaced by matching new windows.

The West Market Diner, dormant now, was constructed in 1921 with a “railroad car” from famed diner designer Mountain View added in 1948 at 659 West 131st under the Viaduct. The company produced diners between 1939 and 1957. photos: Manhattanville, Old Heart of West Harlem, Eric K. Washington, Arcadia 2002

Diner danger: is it the trans-fats ban? NYC’s classic diners are disappearing; The Moondance, 6th Avenue and Broome Street, and the Victory, Richmond Road and Stobe Avenue in Dongan Hills, have closed, as well as all three on 11th Avenue from 37th to 46th Street.

One more along West 131st Street: what used to be, I think, Highland Fuel.

At West 134th the Viaduct ends its M.C. Escher-ian run, and a huge, impressive pile of stonework carries pedestrian traffic to Riverside Park.

The Claremont

The Claremont Theater, possibly Manhattan’s oldest extant movie palace, opened in 1914. The white terra cotta theater was designed by Gaetan Ajello (1883-1983). It has been used as a movie theater, dance hall, auto showroom (as early as 1933!), roller skating rink, retail shops, and presently, for self-storage.

Thomas Edison filmed a crowd exiting the Claremont in 1915.

Atop the Viaduct. At West 134th is a mystery: a large building, used again as storage, with a mighty Greek-style pediment and pillars facing the Hudson, marked Lee Brothers, Inc. What could this have been?

The Viaduct roadway is completely new: it was rebuilt from 1987-1988.

A look at a couple of the mighty apartment buildings facing the Hudson on Riverside Drive concludes our trip to Manhattanville.

Columbia University has bought up much of the property from Broadway west to the Riverside Viaduct and is planning massive changes.

Source: Manhattan, Old Heart of West Harlem, by Eric K. Washington, Arcadia 2002

erpietri@earthlink.net

Photographed July 2006, May 2007; page completed July 23, 2007

©2007