So far September 2007 had proven much cooler than October 2007, which had seen July-like temperatures, at least until the 7th. September was perfect for a breezy walk along West Street from the Chelsea Piers sports complex south to Canal, revisiting places I had not seen for a few years. As it turns out I didn’t see them again, since West Street has changed mightily in those years…

I began my trip at West 17th Street, which, lacking any tall buildings for three of its four West Street corners, presents several views of New York ancient and modern. For example a view of the Chelsea Piers golf driving range also allows a view of the yacht mooring area–as well as the remnants of Pier 58, which once, along with Pier 57, was the home of the Grace Line, co-founded by William R. Grace (1832-1904), the first Catholic mayor of NYC who served two terms from 1881-1889. He accepted a gift from France — the Statue of Liberty — in 1886. The Grace Line was one of the foremost passenger and shipping businesses in the USA until the late 1960s. The Grace Line was sold in 1969 and these pilings are what is left of the Grace Line in NYC.

Sailing ships no longer patrol the Hudson River on their way to every location on the globe. We now have a stylized representative of one in the new IAC (InterActiveCorp) Building (home to a conglomerate owned by media mogul Barry Diller), a Frank Gehry design, on West and West 18th Streets. It is Gehry’s first building in NYC, though he hopes to build more at the massive Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn.

Looking toward a clear view of the King of All Buildings as well as some additional construction, quite a contrast from the low-rise buildings that previously dominated the far West Side. The old freight line, now known as the High Line (seen just below the ESB) is receiving a multimillion dollar makeover as a lengthy urban trail, along which are springing up a number of luxury residences and expensive restaurants.

Pier 58 and the back edge of the Pier 57 building (see below).

Bicycle stoplight at the newly completed bike path along West Street. The path runs from the Battery continuously into Harlem.

The bike path is relatively narrow, and caters more to serious bike riders and racers; sightseeing is pretty much not for you if you want to use this bike path. Better to sightsee on foot, as your webmaster did; there’s a a separate path for just that.

The Hudson Depot or Hudson Pier Depot was located on Hudson River Pier 57 at 15th Street in the present Hudson River Park in Chelsea, Manhattan. It was opened in 1971 and closed on September 7, 2003, transferring many of its routes to the reopened 100th Street Depot. wikipedia

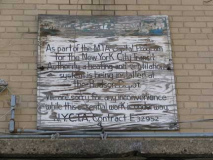

Pier 57, and its large brick building, were completed in 1954 opposite West 15th Street, replacing an earlier Grace Line pier that caught fire and burned down in 1947. It was an innovative design that eschewed pilings and instead employed floating concrete boxes. After the Grace Line was purchased in 1969 its building was used as an MTA bus garage and maintenance facility until a couple of years ago when it became a part of the new Hudson River Park, where its use is still under discussion.

Of particular attraction to your webmaster are a number of wall units of the 1950s-era “Whitestone Bridge poles,” the free-standing variety of which were used on most NYC highways from the 1950s through the 1970s. The pole featured a straight mast with a large “fin” supporting it. We also see the “second generation” of the Westinghouse OV-25 luminaire, redesigned in the mid-60s with their photocontrols (the item that turns on the light at dusk) set toward the back. Your webmaster, a luminaire aficionado, considers these the coolest modern-day streetlamp luminaires ever designed.

Got legs and knows how to use them. The new Standard New York, the latest in a chain by hotelier André Balazs, straddles the rebuilding High Line along Washington Street between Little West 12th and West 13th Streets. It is expected to open in late 2008.

Hudson River Park’s light posts are replicas of the ones in use on the Triborough Bridge and formerly, Bruckner Boulevard in the Bronx. This one can be seen opposite Jane Street.

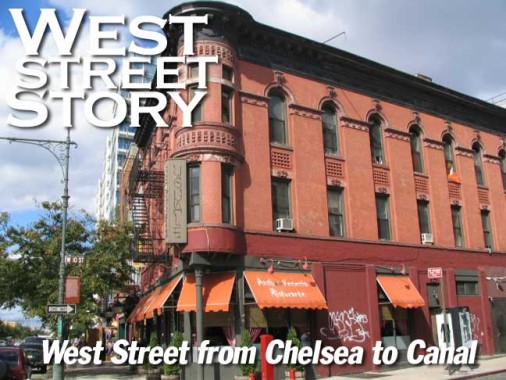

The American Seamen’s Friend Society Institute, at Jane and West Streets, was built in 1910 by architect William Boring and has also been known as the Jane West Hotel and the Hotel Riverview. Its octagon tower once held a beacon that could be seen from Hudson River shipping. In 1912, it hosted survivors from the Titanic, which was to be berthed nearby at the Cunard piers. It has recently [2008] been purchased for $34M by a partnership including hospitality impresario Sean McPherson, who are transforming it into a tourist hostel — not without an outcry from the current occupants who are protesting pending evictions.

463 West Street, between Bethune and Bank Streets, was built between 1880 and 1900 and was originally the home of Western Electric and later, Bell Laboratories. The vacuum tube, radar, sound movies, and the digital computer were all developed here between 1912 and 1937, and the first TV transmission (a speech by Herbert Hoover) occurred here in October 1927. In July 1922, radio station WEAF (named for Earth, Air and Fire) began broadcasting here; it later became WNBC and, at AM frequency 660, broadcast until October 1988. WFAN has been on 660 since then.

The complex, renamed Westbeth for the streets it borders, was converted to housing in 1969 to provide needed living and studio space for artists who could not afford spiraling rents.

Photographer Diane Arbus committed suicide here, July 28, 1971.

Stylized original wall lamp stanchion

In 1997 your webmaster saw Ray Davies here on the head Kink’s autobiographical Storyteller tour.

The changing face of Charles Lane. Once the lane that ran along the north side of the old 1797 State Penitentiary (moved to Ossining in 1829 and nicknamed “Sing Sing”) Charles Lane now runs between the twin towers comprising Richard Meier’s glass-faced Perry Street exclusive condominium development. RIGHT: Charles Lane, 1999. This section is mostly intact.

Charles Lane (1905-2007) was also a busy character actor who appeared in over 300 films and TV shows between 1931 and 2006, usualy playing dyspeptic or annoyed bank clerks, judges, professors or clergymen.

Another couple of looks at the Meier complex; compare with older building at West and Charles Streets.

Hello there. 403 West Street near Charles.

Uguale, Italian for “equal”, a bistro in an impressive arched-window building at West 10th and West Streets. It is a former waterfront hotel built in 1904.

At Amos Dock [West 10th Street’s former name is Amos Street] on July 26, 1854, boxer John “Old Smoke” Morrissey fought a match with Know-Nothing gang leader “Butcher Bill” Poole, who “bit and gouged but won only when his friends joined the fight and kicked Morrissey unconscious”–New York Night. Morrissey’s friends later fatally shot Poole at Broadway’s Stanwix Hall. Songlines

Weehawken Street is a one-block alley just east of West, between West 10th and Christopher Streets. It is named for Weehawken Market located here from 1834 to 1844 at which farmers from Weehawken, NJ, just across the river, sold produce. Competition from Jefferson Market at 6th Avenue and West 9th Street (the Ruskinian Gothic library at the site at present remembers its name) put the Weehawken Market out of business, but its space lives on as this alley. A leg of Canal Street (see below) at West Street was called Hoboken Street in the 1800s.

Newspaperman Jack Fanelli (played by Michael Levin) of TV’s Ryan’s Hope (which also starred Kate Mulgrew of Mrs. Columbo and Star Trek fame) lived on Weehawken Street.

Six wood frame houses were built on Weehawken Street in 1849. One, #6 Weehawken, is still there, with the back end on West Street. Here’s one of the newfangled glass bus shelters.

Ladies, would you wear that getup in the bus shelter ad? You tell me.

Wee signs. West Street between Charles and Barrow Streets has been the nexus of the gay bar and club scene in the past, and Weehawken Street’s residents have battled drunks who used the narrow lane as a pissitorium. About 15-20 years ago these well-calligraphed signs appeared; a local artist must have lettered them. They’re quite well done and the letters remind me of the work of the USA’s pre eminent man of letters, Frederic Goudy.

384 West at Barrow Street was Keller’s, perhaps New York’s first leather bar–dating to the 1950s. It’s also been credited as the birthplace of disco; the Village People were photographed here for an album cover. Closed in 1998. Originally the Keller Hotel, built in 1898. Songlines

Till recently a Southern BBQ joint called Rib, and before that the Lunch Box Food Co., this classic chrome diner is squeezed between auto supplies shops on West near Clarkson.

In 2012, Scouting NY reported:

Designed in the 1950′s by the Kullman Building Corporation, famous for their iconic diner designs throughout the northeast, 357 West Street was at least known as the Terminal Diner through 1989…

According to RoadsideArchitecture.com, it later became the appropriately named Lost Diner in 1991, Seafood Organic by 1997, the Video Diner by 1999, and later, the Reel Diner and Miss Liberty Diner. In 2002, it was restored as the Lunchbox, and finally became Rib in 2005. Rib closed in 2006, and it’s been abandoned ever since, wasting away a little more each day.

By 2012, it had really deteriorated.

Said auto supplies shops.

At first this ordinary looking brick building at Canal and West might attract little notice, but a closer look reveals a plaque dating back to the John Hylan administration (Hylan was the mayor just before Jimmy Walker) when the Department of Sanitation was called the Dept. of Street Cleaning.

A park has recently been restored to the triangle formed by Canal Street’s fork and West Street, which for 83 years was a bricked and later, blacktopped parking area. The photo at right is a 1978 view of the present view, with a bishop crook lamp, the old Miller Highway Viaduct, and buildings associated with Piers 32-34. Jeff Saltzman

The land beneath Canal Park was originally granted to the city in 1686 by James II, and was once a drainage point into the Hudson River from the former Collect Pond on the east end of Canal Street. Once the pond was closed in the early 19th century, and the pier at the west end of Canal became commercially active, the land was drained and developed. This, combined with the new city street grid of 1811, established the triangle as a public square and pedestrian throughway to the Hudson River.

That busy square evolved into the Clinton Country Market in 1849, officially dedicated as park land in the 1860s, and landscaped by 1871 — one year into the existence of a then-new city agency called the Department of Public Parks. Trees and shrubs were planted in the park’s center, a fence was installed around its perimeter, and the surrounding sidewalk served as the city’s Flower Market.

The neighborhood’s industrialization came back into play in 1921, when the city loaned the park’s land to the NY/NJ Bridge and Tunnel Authority to use for construction of the Holland Tunnel. What began as a four-year loan lasted nearly a decade, and by then the area had become so commercial that the city chose not to rebuild the park.

By the 1990s, the park had all but escaped the public’s memory — until Richard Barrett and other members of the Tribeca Community Association took a closer look at the effects of a revamped Highway 9A (West Street) on Tribeca, and discovered the park’s storied past. The small group soon formed the Canal/West Coalition, whose goal was to restore the park to its 1888 design and organize the traffic that swirls around it. LowerManhattan.info

The restored Canal Park opened in 2005. It is still rather hard to get at, given Canal and West Streets’ roaring traffic.

The Holland Tunnel pulsates beneath Canal Street. Its large ventilation building, seen in the park photo above, and its gilded door at left, are interesting 1920s solutions to utilitarian building design. Above: building on Washington Street near Canal. Emblematic of the subtle touches designers made on unheralded office buildings in the early 20th Century.