The ghost of George Washington is all over New York City. There he is taking the oath of office at Federal Hall at Wall and Nassau Streets…he’s bidding farewell to his charges at Fraunces Tavern…he’s on horseback in Union Square and at the Williamsburg Bridge…two of him at Washington Square Arch…wearing his Masonic apron in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. There are eight thoroughfares, two bridges and two parks named for him in Manhattan; three roads apiece in Staten Island and Brooklyn, and one in the Bronx (Queens, which is mostly numbers, doesn’t).

Today’s topic, Manhattan’s Washington Street, originally ran from Battery Place on a nearly straight line north to West 14th Street a block west of Greenwich Street. Manhattan’s west coast in this area was built on landfill in the late 18th Century and early 1800s; Washington Street first appears on maps about 1797, when it faced the Hudson River. Greenwich Street preceded it by a few decades, as the Road to Greenwich (Village) and it, too, originally hugged the coast and even has retained a few zigs and zags to let us know that it once did.

Time hasn’t been kind to the southern reaches of the street named for the father of our country, as multiple construction, destruction, and construction again has sundered it to pieces beginning in the 1950s, when first the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, then the World Trade Center, and then the Independence Plaza housing complex were built in succession. Yet, bits of Washington Street are still holding firm in some areas, and a piece of it only recently was built over.

Though Washington Street runs continuously north of Hubert Street, it only runs intermittently south of that. For our first piece of Washington we look in the heart of the housing complex known as Independence Plaza, completed in 1975, which replaced most of the old Washington Market area. For over 190 years, from the 1770s through the 1960s, this was the heart of Manhattan’s produce market; goods loaded off the docks at the Hudson River would be trundled over the Belgian-blocked streets by horse and cart, later by truck, to dozens of busy wholesalers who crowded the blocks from Fulton north to Hubert and from the river to Greenwich. The original market occupied a the block formed by Washington Street, West, Fulton and Vesey. Beginning in the late 1960s, as the World Trade Center came closer to being, NYC’s wholesale produce market relocated to Hunts Point in the Bronx (where, 30 years later, the Fulton Fish Market also decamped). When these institutions left Manhattan they took some of the borough’s character with them.

Though the massive yet quite mundane Independence Plaza now dominates the old Washington Market area, there’s a break in the action at Greenwich and Harrison Streets, where you will find a smattering of tiny Federal-style townhouses, six facing Harrison Street. These houses were all built from between 1790 and 1820 and have been conferred designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Yet, three are not in their original locations: they were once about a block away, on Washington Street. (Two, 27 and 27A Harrison, were built by Jonas McComb, one of the designers of City Hall). After the Landmarks designation in the early 1970s the three were jacked up and towed by truck to their present location on Harrison Street; in the above photo, they are the three houses on the left side. The three remaining Harrison Street houses, 29, 31 and 33, have always been there. The first floors of most of these buildings had been given over to commercial establishments, but all the houses were given complete restorations by the Herbert Oppenheimer architectural firm, restoring their old Federal fronts and new interiors after a couple of centuries of wear and tear.

Which brings us to our Washington Street remnant…

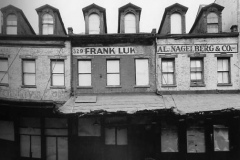

331, 329, 327 Washington Street, 1969. Photo: Danny Lyon

The same buildings today, renumbered, are on a short slice of Washington Street that is a dead end running south from Harrison Street. During the Washington Market era the buildings were throuroughly commercialized, but now they have been returned to their residential origins; and have kept a piece of their original street to boot.

This is all that remains of Washington Street in the old Washington Market area.

(LEFT) Now dominating the area is the architecturally vapid Independence Plaza.

Returning briefly to Harrison Street, it too has a secret to the past of what was once called the Lower West Side. Looking toward Jersey City across the Hudson, in the foreground is West Street (given the sobriquet Joe DiMaggio Highway in 1997). It’s the former site of the elevated Miller Highway and the failed site of what would have been Westway, a combined underground highway and park. Though the project was relentlessly opposed and ultimately defeated by neighborhood groups (a judge declared it would jeopardize the striped bass in the Hudson River), your webmaster doesn’t think an underground highway covered by a park would have been all that bad an idea, especially with the pedal to the metal West Street traffic that makes crossing it an urban daredevil site.

A remnant of the old Miller Highway is still here on a pedestrian overpass above Harrison Street, though: one of the Machine Age-style identification friezes that appeared on the Miller above every cross street. In an era when the docks were much more important that they are now, the pier accessible from the street was indicated on the frieze as well.

Miller Highway: NYCRoads’ historic overview

Five blocks south of Harrison Street, a very small parcel of the area north of the World Trade Center had been left undeveloped, oddly enough, and the plot defined by West, Greenwich, Warren and Murray Streets remained a parking lot until 2005. A small, cobblestoned piece of Washington Street remained as a dead end issuing from Murray just south of PS 234. (The “stub” can be seen at the former Washington and Murray Streets on a 1978 photo by Bob Mulero, left, and a 1999 photo by your webmaster, right.)

This particular piece of Washington Street, and the ancient bishop crook lamppost that highlighted it at Warren Street, were paved over in 2006 and now, this scene forms the foundation of a new mixed-use 32-story tower, 101 Warren Street.

Another Piece

A walk east on Barclay Street from West Street vouchsafes an excellent view of the Woolworth Tower (above left) but also accesses a one-block piece of Washington Street that remains between Barclay and Vesey Streets (above right).

This piece of Washington Street provides views of the green-glass walled 101 Barclay (above). The building at right is the ground floor of the new 7 World Trade Center. This glass-fronted rhombiod was designed by David M. Childs, who will be the architect of the remainder of the new World Trade Center buildings, including the Freedom Tower.

This piece of Washington Street remained mapped during the World Trade Center construction beginning in the late 1960s when most of the rest of it disappeared. Why was it spared?

It’s likely the reason it’s still here is that the back entrance of the 1927 Barclay-Vesey (or New York Telephone or later, Verizon) Building is on Washington Street. The 32-story building, designed by Ralph Walker, is considered the first Art Deco tower in New York City.

The last time I attempted to photograph the front of this building from West Street, I was stopped by a zealous security guard (though I understand why; the building was heavily damaged during the 9/11/01 terrorist attack, and a multimillion dollar restoration project was completed in 2004). Fortunately NYC Architecture has some views of the lobby corridor, which stretches from West to Washington Street, as well as some 1920s views of the skyscraper.

When first built, the Barclay-Vesey faced the Hudson River; later the view was compromised somewhat (for those working on the lower floors at least) by the Miller Highway. Since the 1970s, Battery Park City, formed in part by excavations for the World Trade Center, has eliminated the river view on the lower floors.

The building does have a telephone motif, with sculpted bells above the entrances. Flanking the West Street entrance, though, are also a couple of friezes depicting the Mayan civilization of Mexico and South America. The Mayan Indians preceded the Inca and Aztec in forming pre-Columbian society.

The most surprising and rewarding aspect of the Barclay-Vesey Building, for the pedestrian at least, may be the arched arcade over the sidewalk on the Vesey Street side, vaulted by criss-crossed Rafael Guastavino tilework, which also highlights such NYC locales as the great hall at Ellis Island, the now-retired City Hall subway station, the underside of the 1st Avenue viaduct of the Queensboro Bridge, and many more.

The covered sidewalk motif has been copied practically nowhere else in NYC, except, surprisingly enough, on Roosevelt Island.

The temporary Vesey Street pedestrian overpass is misspelled on the sign. The street name is pronounced, however, as if it did have two S’s: vess’ ee.

We’ll take that bridge to the other side of West Street as we make our way toward the next piece of Washington…

The extended delays in the reconstruction of the World Trade Center site have allowed some views of downtown Manhattan that will be unavailable once the new towers are built. At left, the monolithic black building is #1 Liberty Plaza at Broadway and Liberty Street, originally the U.S. Steel Building: in 1972 it replaced the old Singer Tower; the Equitable Building (1915) behind some shorter Liberty Street buildings; the old 41-story Deutsche Bank building, terminally damaged on 9/11/01: its deconstruction has been plagued by missteps and disasters; and at right, Cass Gilbert’s 1907 90 West Street.

Washington Street commences again south of the World Trade Center site for six short blocks. Street signs in the area, installed by the Downtown Alliance, depict the fallen towers.

Many of the buildings on this stretch of Washington are still enshrouded in protective netting, and sidewalks are still covered by scaffolding. The region west of Broadway and south of Liberty Street has been the slowest to recover from the attack.

Looking north at the gradually fading Deutsche Bank building and the new 7 World Trade Center, background right.

RIGHT: New York Evening Post Building, 110 Washington, built by Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer in 1926.

110 Washington doesn’t look especially interesting on the ground floor, but Michael Daddino’s excellent Masterpiece Next Door reveals its colorful terra cotta work on its upper floors.

The marvelously rococo 103 Washington has been an inn, then a church, and back to an inn again. Built in 1897 and presently downtown bistro Moran’s, it spent most of its history as St. George’s Chapel, which catered to the Syrian Catholics who lived in this vicinity.

Therefore, the former chapel is one of the last remaining vestiges of Washington Street’s former Syrian and Lebanese-American community, clustered along the thoroughfare from Battery Park north to the World Trade Center site and fueled by immigration from the Middle East around the turn of the 20th Century. Beginning in the 1920s, however, many moved away to Bay Ridge and downtown Brooklyn. The construction of the WTC in the late 60s and early 70s displaced many of the remaining families.

The earliest immigrants that we would call Arabs had Turkish passports because of the reach of the Ottoman Empire. But most spoke Arabic and came from Syria and what is now Lebanon. The majority were not Muslims but Catholics, divided among Maronites and Melchites. There were Syrian Orthodox and Syrian Jews. Once here, they were known as Syrians.

This is the community that settled on Washington Street. From the late 19th century until the building of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel in the 1940s, Manhattan’s Little Syria was home to countless immigrants from Syria and Lebanon, again most of them Christian. They were bankers and publishers as well as manufacturers and importers of lace, linen, embroideries and lingerie.

Philip Kayal, a professor at Seton Hall University who wrote “New York: The Mother Colony of Arab-America, 1854-1924,” said, “This community was an entrepreneurial community, it wasn’t an educated community. It had been influenced by French imperialists. They thought like Western Europeans for the most part.” Gotham Gazette

Washington Street comes to an abrupt end once again at the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and the large parking garage that serves traffic heading for downtown. A narrow alley, Joseph P. Ward Street, was constructed in 1951 to connect Washington and West Streets after the former was cut off by the tunnel. The lane (left), which is shrouded by the parking garage, was named in 1967 for a decorated World War II radio operator according to Sanna Feirstein in Naming New York.

We need to detour to West Street once again to get past the Tunnel traffic (which, oddly enough, issues to a surface traffic throughfare, West Street; motorists have the option to follow West north to the Di Maggio Highway and Henry Hudson Parkway, or south to the FDR Drive). A block south is Morris Street, which is subtitled…

…(Thomas) “Teddy” Gleason Street, named for the longtime President of the International Longshoreman’s Association from 1963-1987.

The large orange and brown-glazed tower, 21 West Street, was built with its neighbor the Downtown Athletic Club in 1931 and 1926 respectively by Starrett and Van Vleck.

Turning down Morris Street yields a pleasant surprise.

A remaining “Type G” “Corvington” lamppost, (desecrated with a sodium luminaire; it’s like putting Phyllis Diller’s head on Heidi Klum’s body). This one has also been compromised at the base, which usually goes with a taller type 24M Corv.

Another view of the garage from Morris across the Tunnel. Your webmaster once interviewed for Kinney System unsuccessfully for a job here at the garage doing layouts for promotional materials.

Where Morris Street is interrupted by the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel we find our final one-block piece of Washington Street, which runs south to Battery Place. This stretch is officially known as Western Union International Plaza, after its longtime headquarters at 1 Western Union International Plaza (2 Washington Street). The money transfer company, which no longer handles telegrams, hasn’t been on Washington Street since the 1980s, but the name sticks.

At the risk of sounding ancient, your webmaster’s pal Brian worked a telex machine at 1 WUI Plaza in the early 1980s.

A view of 21 West Street from the pedestrian bridge spanning the tunnel entrance. It has been there since the tunnel was constructed. (RIGHT) note the swastika motif on 21 West. Before the Nazis forever ruined its reputation, the swastika was a symbol of good fortune.

Washington Street used to boast a pair of Corvington poles between Morris St. and Battery Place. One remains (above photo) but one was taken out by a truck some years ago.

Washington ends, or begins, at Battery Place, which runs along the northern end of Battery Park. The park, and street, are named for gun batteries set up by the British to guard the harbor entrance in the 1680s.

The massive concrete slab at the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel entrance is, as far as the public knows, its ventilation building. But deep below the building is a top secret command center where aliens from other planets are processed for immigration and surveilled when necessary.

The big Beaux-Arts pile at 17 Battery and Washington Street is the 1902 Henry Hardenburgh-designed Whitehall Building. It’s named for Peter Stuyvesant’s mansion, Whitehall, not for Whitehall Street, a couple of blocks away. Its even larger rear addition was built 8 years later. When built, this was the big dog in the neighborhood, a stand-alone skyscraper, as these postcard images from NYC Architecture will show. Your webmaster also interviewed unsuccessfully in this building.

The city is rebuilding Battery Place and on the park side, has left a sea of concrete. Is this what the city really wants here?