Even though the Brooklyn Navy Yard in Fort Greene has not served the U.S. military for decades (it was a naval shipbuilding enclave from 1801 to 1966), it remains a zealously guarded private enclave featuring industrial businesses and movie studios.

The Navy Yard reached peak production just before and during World War II:

On the eve of World War II, the yard contained more than five miles (8 km) of paved streets, four dry docks ranging in length from 326 to 700 feet (99 to 213 meters), two steel shipways, and six pontoons and cylindrical floats for salvage work, barracks for marines, a power plant, a large radio station, and a railroad spur, as well as the expected foundries, machine shops, and warehouses. In 1937 the battleship North Carolina was laid down. In 1938, the yard employed about ten thousand men, of whom one-third were Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers. The battleship Iowa was completed in 1942.

At its peak, during World War II, the yard employed 70,000 people, 24 hours a day. Unfortunately for its workers, the Brooklyn Navy Yard made extensive use of asbestos in the manufacturing and repairing of its ships during the twentieth century. While the federal government successfully resisted responsibility in court for the extensive and often mortal health problems that resulted in the following years, thousands of retired workers have successfully sued the private businesses that supplied asbestos products to the U.S. Navy. wikipedia

Your webmaster has entered the Navy Yard only twice, and only once on foot. I attended an art exhibit in the spring of 2006, and a couple of years earlier, I rode the fireboat John J. Harvey as it entered the Navy Yard through Navy Yard Basin, and got a brief glimpse. Otherwise, like most of interested Brooklynites, I’ve pretty much seen it only from its bordering streets, Flushing and Kent Avenues. At the Yard’s southwestern edge, on Flushing Avenue between Navy Street and Carlton Avenue, you’ll see the rapidly deteriorating and weedy Admirals’ Row (a.k.a. Officers’ Row), a number of residences formerly housing the Yard’s naval commanders.

I’d despaired, though, of ever being able to see the Navy Yard’s other historic buildings. Then I received a message from a ForgottenFan, Edward J. Keenan, USN, Battalion Medical Chief, 2nd Battalion, 25th Marines, FMF, who sent me a number of photos taken by the US National Park Service for the purposes of Landmark Designation for the National Register. They are the best photos of their type that I’ve yet seen. They were taken between the years 1963 and 1973.

The marble Greek Revival US Marine Hospital, later US Naval Hospital, north of Flushing Avenue between Ryerson Street and N. Williamsburg Place, is a landmarked building completed in 1838.

Built in 1830-38 the US Naval Hospital (formerly the US Marine Hospital) is a two-story, 125-bed Greek Revival structure in the shape of an E. The refined granite building contains a recessed portico with eight classical piers of stone that reach the full height of the building. Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Landmarks of New York

Occupying the same property as the hospital, the Surgeon’s House follows the style of the French Second Empire with its low, concave mansard roof and dormer windows. It is a two-story brick structure divided into two main sections, the house proper and a servant’s wing, together totaling sixteen rooms. The symmetrical entrance facade has a central doorway flanked by segmental arches and low balustrades. Also on the first floor is a handsome, projecting three-sided bay window; on the second floor, segmental-arched winodws rest on small corbel blocks. The side elevations of the house show both segmental-arched and square-headed windows. Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Landmarks of New York

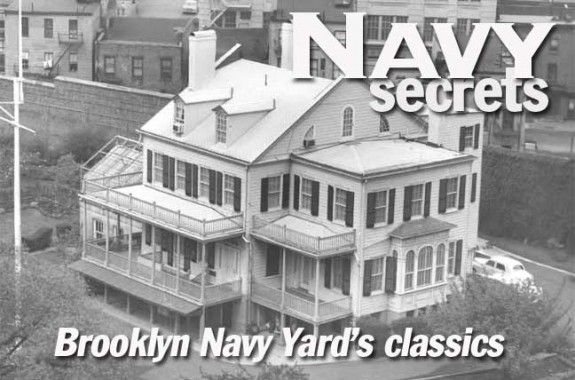

The eldorado, though, was seeing the Naval Commandant’s House close-up. I had only seen this Federal-Style building, the home of all the Navy Yard’s commanders until the 1940s since its completion in 1807, from a gate on Little Street or behind a high wall on Hudson Avenue. I was supplied with two views, one of its rear porches and another from the air. The New York Times’ Christopher Gray got a rare trip past the wall and into the house in June 2006…

[Photographs] from the early 1900’s show an elegant interior, with Federal-style mantels, door casings, interior fanlights and an oval dining room, a far more ambitious house than, for instance, the 1804 Gracie Mansion.

Matthew C. Perry was commandant for two years starting in 1841. In 1853, he signed the treaty that opened Japan to foreign trade.

In fact, the terms of office in the 19th Century seemed to run rather short: Perry’s successor, Joshua Sands, was commandant for only a year. The next commandant, Silas Stringham — who fought the slave trade off the African coast and pirates in the West Indies — served from 1844 to 1846.

It was halfway through his occupancy that The Brooklyn Eagle visited Quarters A and wrote that the house, “with its lawns, terraces and teeming gardens, is a conspicuous object.”

An Eagle reporter returned in August 1872 and wrote that, along with its orchard and vegetable garden, Quarters A had “a look that makes one feel that it must be a pleasant thing to be the commandant.” That was during the four-year term of Stephen C. Rowan, a Civil War veteran.

Quarters A is surrounded by a steep fenced drop-off into the old Navy Yard, a long seven-foot-high brick wall; and a high iron fence with a locked gate. It is possible to glimpse the house over the wall and through surrounding empty lots — you can spot a chimney here, a gable there. But the only reasonable view is through the gate, at the foot of Evans Street, off Hudson Avenue. Parked along the driveway are several vintage cars, including a 50’s Studebaker. Perhaps 100 yards away, you can see a rear corner of the house.

The Federal-style detailing is crisp enough to see at a distance, as are some spectacular quarter-round windows on the top floor. But elsewhere there is peeling paint, and some of the shutters seem near collapse.

Nicholas Evans-Cato, an artist who has a studio nearby, was in the house in the 1990’s and says that according to local lore, the oval dining room has the same proportions as the Oval Office.

“It’s literally our own little White House,” he said.

1/28/08