There has been a gradual coalescing of my observations as I walk through Brooklyn in the mid to late 2000s. The era when Brooklyn worked — as in manufacturing and supplying the world with the fruits of American know-how and technical expertise — is coming to an end. It’s being replaced by service industries, housing, and tourism. I don’t even know if I should be all that riled about it, as long as the architecture where people formerly toiled now houses people who are primarily relaxing. I’ve taken to calling it the Eloi-zation of NYC, as toilers are replaced by partiers….

My term Eloi-zation comes, of course, from H.G. Wells; the British writer’s first successful science fiction story in 1898, The Time Machine, depicts a time traveler (how he travels is not revealed; there’s only the description of his machine) who goes to the 803rd Century, by which time the class distinctions between the working and leisure classes of turn-of-the-century Britain have become so pronounced as to produce two separate devolved human species: the reclining Eloi, who sit in the sun all day, and the blanched underground Morlocks, who run the planet, providing the Eloi with enough food so they can prey on them later.

Brooklyn is not likely to produce a devolved humanity anytime soon, but we have certainly moved on from the days when Brooklyn worked and are entering a time of Brooklyn’s leisure era. Is that a good thing? We’ll have to see.

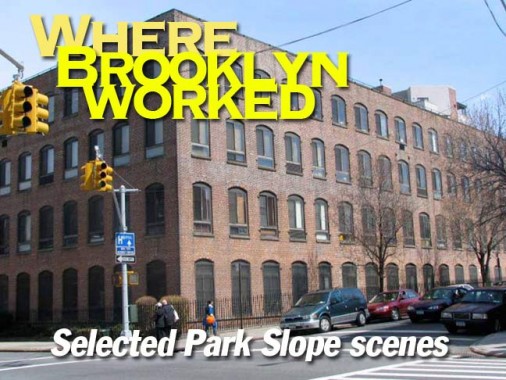

In 2007 I took a walk through Park Slope and snagged a few items of interest…among them some buildings formerly used as factories and now residences, some of them pricey.

On the north side of 9th Street between 4th and 5th Avenues is one of Brooklyn’s most beautiful residences, a textbook Second Empire style with a slanted mansard roof, moldings, bay windows and best of all, a cupola open on three sides. It’s been the home since 1981 of jazz musician and teacher Charles Sibirsky. When it was built, Park Slope was open country.

The mansion, built for Wall Street nabob William B. Cronyn in 1852, became the headquarters of the Charles M. Higgins India Ink Company in 1898. The actual factory building still stands as well, directly in back of the mansion on 8th Street. The inkmakers, though still going strong, moved out about thirty years ago.

Green-Wood Cemetery’s famed Minerva statue, which waves to the Statue of Liberty, was commissioned by Higgins, who also built his mausoleum behind the statue.

For all my scoffing about Brooklyn becoming Leisureworld, I’m a fan of brick factories that have become residential complexes. (I live in a co-op complex in Little Neck that resembles the old Ansonia clock factory, which takes up almost the entire block between 7th and 8th Avenues and 13th and 14th Streets.)

Ansonia was founded in Derby, Connecticut in 1851 as a subsidiary of a brass business run by Anson Phelps in the Naugatuck River valley. Ansonia shelf clocks are still very collectible today, with their expert craftsmanship and accurate timekeeping: the firm’s clock cases were made of mahogany, rosewood, and other quality materials. Ansonia moved to Brooklyn in 1879; their original factory there burned down immediately, but the second is still here on 7th Avenue between 12th and 13th Streets.

Active clock production at Ansonia Clocks ended about 1930, whence the machinery was sold off to a Russian manufacturer. Recently, the factory was divided into apartments and renamed Ansonia Court. The only reminder of the Ansonia days is the sign on Astoria Optical, across the street on 7th Avenue.

The Factory stopped being a factory in the late ’70s, and bohemian types, musicians and artists, started renting loft space. Then, to everyone’s amazement, The Factory was converted to condos in the ’80s and renamed Ansonia Court. I’d say more than half the guys I hung out with in The Factory are dead now, some lost to street violence, some to drugs, booze, cancer and war.

But last week, as I stood under the big clock of the Williamsburgh Bank Building, 40 summers later, I learned they were getting $800,000 for two bedrooms in The Factory, and I just had to close my eyes in the warm July sun and shake my head and laugh. Denis Hamill

The Litchfield Villa, Prospect Park West opposite 5th Street, like the nearby Quaker Cemetery (final resting place of actor Montgomery Clift) was absorbed into Prospect Park since it was here long before the park was even conceived.

The mansion was completed in 1857 by architect Alexander Jackson Davis. Edwin Litchfield, founder of the Brooklyn ImprovementCompany that dredged the Gowanus Creek (now the Gowanus Canal) owned all the land from about 1st to 9th Streets and from the Gowanus Canal to about 10th Avenue, which at one time did go through here, at least on paper. In 1868 the city of Brooklyn acquired the territory for Prospect Park, which was built around the house.

The mansion was constructed in Italianate style and named Grace Hill for Litchfield’s wife. Currently it functions as the Brooklyn HQ of the NYC Department of Parks, and is open to the public.

I’ve always wondered what’s the story behind these homes on 13th Street between 7th and 8th (opposite the Ansonia). They are set far back from the street and have huge front yards. In this, they remind me of the blocks of 1st -4th Places in Carroll Gardens built by Richard Butts.

About 4 blocks away on Prospect Park West and 1st Street is the ashlar-faced 1889 Henry Clayton Hulbert house, built for a wealthy financier and paper-supplies industrialist by architect Montrose W. Morris, who specialized in Romanesque Revival buildings like this one. (Will the glass towers that dominate NYC architecture these days be given names like Ruskinian Gothic and Second Empire? I sort of doubt it.) Morris’ most famed Brooklyn building may be the Alhambra Apartments on Nostrand Avenue north of Fulton Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant, also built in 1889. It was a very good year.

Before we kick it in the head, some Slope minutiae: dozens of brownstone fronts have gaslamps, mostly all of them powered by electricity; at 6th and 6th, some of the blue and white signs that proliferated before signs were hung on lampposts; and a haberdasher ad uncovered in 2007 on 4th Avenue near 8th Street.

9/10/08