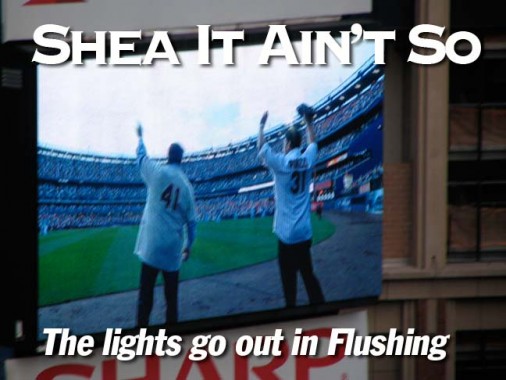

Everyone at Shea Stadium on September 28, 2008, except members of the Florida Marlins — over 55,000 people — were hoping that the date would not mark the final game at Shea Stadium of Flushing Meadows, Queens. The Marlins, however, prevailed 4-2, ending hopes for any more post-season baseball at the 45-year old bucket of bolts, proclaimed a ‘dump’ by Mike Piazza in his playing days here in the 1990s. Even the most fervent Met fan couldn’t disagree; yet, when the lights went out (literally) at Shea at the conclusion of the closing ceremonies, Thomas Wolfe’s phrase “you can’t go home again” gained more poignancy as we all realized we’d never be going to Shea again. On this, um, “very special” Forgotten NY page, I’ll take a look at the Stadium and some of its quirks, and tell you about some of the strange and wonderful games I had attended there. Yes, I have to use the past tense; crews began to disassemble the place the following week.

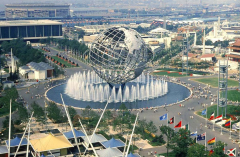

The Unisphere, still the focal point of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, can be seen in the center of this photo. Other prominent buildings are the Fair’s New Jersey Pavilion (the series of hexagon-shaped buildings seen left center, and the USA Pavilion, the large, glass-paneled building seen just below Shea. photo: baseball fever

Shea Stadium, which can be seen at the top of the photo along with its ‘sister” stadium, the Singer Bowl, now Louis Armstrong Stadium (seen just above the Unisphere), came into being along with the last NYC World’s Fair in 1964. It was named for attorney William A. Shea, who, after the Brooklyn Dodgers left for Los Angeles for the 1958 season (and the Dodgers have now called LA home longer than Brooklyn by now) worked tirelessly for National League baseball to return to New York City. His committee first attempted to get the Reds, Phillies or Pirates to move to New York (can you imagine stars of the era like Frank Robinson, Richie Allen or Roberto Clemente with “New York” displayed on their uniforms?). None bit, so Shea and Branch Rickey formed a new major league — the Continental League — that would rival the NL and AL. In reality, this was a ruse — a bluff — to get the National League to place a team in NYC. MLB expanded — added new teams — for the first time in decades in 1962, with the NL plucking the New York and Houston franchises from the CL; the AL, in 1961, added the California Angels, moved the Washington Senators to Minnesota and instituted a new Senators franchise in DC, which would move to Arlington, Texas in 1972. Charles Shipman Payson and his wife Joan (a Shea fixture for many years) were the principal owners of the Mets along with George Herbert Walker Jr, an uncle of President George Walker Bush. When Joan Payson passed away in 1975, Charles delegated operations to daughter Lorinda and chairman M. Donald Grant, who traded Tom Seaver during a salary dispute in 1977.

The Paysons sold the Mets to the Doubleday Publishing company in 1980, with Nelson Doubleday becoming chairman and Fred Wilpon, a minority owner, becoming president. Wilpon quickly hired former Orioles exec Frank Cashen, who built the Mets into a league powerhouse in the late 1980s. Wilpon purchased the Mets from Doubleday and became sole owner in 2002.

The Mets played in the Polo Grounds, the old home of the New York Giants, for two years while Shea Stadium was built. Thereafter the Polo Grounds was razed with little fanfare; nothing remains of it, except a staircase that fans used to ascend Coogan’s Bluff after the game was over.

In the Beginning

When Shea Stadium opened April 17, 1964 Shea Stadium was essentially unfinished, despite being under construction since 1961. When the crowds filed in, paint on the wood seats was still wet. Very few telephones in the stadium worked — telephone workers were on strike. Jack Fisher, who was introduced at the 2008 closing ceremonies, threw the first pitch; Florida’s Matt Lindstrom threw the last in 2008. Pittsburgh’s Dick Schofield (whose son Dick was a Met in 1992) was the first batter at Shea (resulting in a popup); the Mets’ Ryan Church was the last, in 2008 (a hard hit fly ball to CF). The Pirates’ Willie Stargell hit the first home run at Shea (also the first hit), while Florida’s Dan Uggla hit the last Shea home run; Carlos Beltran hit the last Mets home run.

Of the Mets who played in that first game, Ron Hunt, Frank Thomas, Fisher, and Ed Kranepool appeared at the closing ceremony; Jim Hickman was invited but did not come. photos: baseball fever

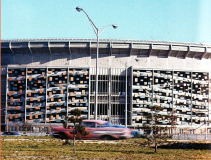

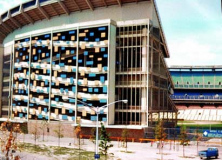

From the outside, Shea’s most notable features were the blue and white panels that hung on the outside, by the inside ramps. They were made of very heavy corrugated metal and defined Shea’s visual imprint from 1964 through 1980, when Wilpon and Doubleday, who wished to update the Stadium’s look, had them removed. The panels (the blue ones slightly outnumbered the orange ones) perfectly matched the neighboring World’s Fair’s kandy-koated esthetic, but did look a bit dated by the Easy Eighties. Unfortunately, none have been preserved: all were scrapped when they were removed.

Crowds assemble outside Shea on its final day of operations, September 28, 2008. Look closely photo right and you can see the vertical wires that supported the orange and blue metal tiles; they were never removed, and theoretically, new tiles could have been installed if the Mets wanted to bring back a retro look.

In 1985 or 1986 (I forget which it was) Shea Stadium became awash in blue (strangely it was more of an indigo blue, somewhat darker than the blue the Mets feature on their uniforms) as well as five large abstract baseball-themed neon designs, one above each gate. This scheme remained in place until the end of Shea’s run in 2008.

My first game at Shea

I didn’t become a baseball fan until early in 1969, when I was eleven. I’m not sure exactly why but I became a Met fan and followed them on TV and radio, and then on June 1st, 1969, my parents and I would make our first visit to Shea. The game was a Saturday afternoon tilt with the San Francisco Giants of Mays, McCovey and Marichal and the Mets prevailed 5-4 in a back-and-forth contest. Catcher Jerry Grote drove in the winner with a bags-filled walk in the 9th inning. It was the Mets’ 4th straight victory in an 11-game winning streak that would bring them into the thick of things in the newly-designated National League East.

I purchased the Mets’ 1969 yearbook that day; the cover is shown at left, with the Mets’ three 1968 All-Stars, Jerry Koosman, Jerry Grote, and Tom Seaver, pictured superimposed on a jammed Shea.

Needless to say, 1969 was a great year to become a baseball fan, as the Mets, a 100-1 shot, came on strong in September and October and won it all on the strength of lights-out pitching led by Seaver and Koosman.

If you look at the roster, though, the accomplishment becomes even more impressive, as manager Gil Hodges got every ounce of production from his roster imaginable. The third-base platoon, Wayne Garrett and Ed “The Glider” Charles, averaged .213 between them, many players on that team such as Jack DiLauro, Bobby Pfeil, Rod Gaspar, who made major contributions that year, never made much of a mark again, and guys like Al “The Mighty Mite” Weis, who usually swung a wet noodle, killed the Birds of Baltimore in the Series.

My favorite player at the time was Ron Swoboda, whose autograph I got when ‘Rocky’ visited the Cub Scouts at St. Anselm Church the previous winter. After struggling most of the year, Swoboda, who had had a golden sombrero (a 4-strikeout game) and a platinum sombrero (a 5-strikeout game) in 1969, hit a grand slam that beat the Pirates, and a two-homer game against Steve Carlton that beat the Cards the night Carlton struck out 19 Mets. Ron made one of the greatest Series catches in history against Brooks Robinson, and then drove in the game-winner in Game 5 with a double. Swoboda, of course, was at Shea on closing day.

To date, no Met has ever pitched a no-hitter, and no Met will ever pitch one at Shea. Whenever a Met comes close but falls short I invoke the 1969 Rule: “In the Book of Gil it is written: ‘No Met shall ever pitch a no-hitter.’ The price of 1969.

[Johan Santana finally pitched a no-hitter at Citifield, 6/1/12.]

In 1969, however, I did attend a no-hitter: on September 20, I watched the late Bob Moose mow down the Mets in the last no-hitter ever pitched at Shea. The first was Senator Jim Bunning’s 1964 Father’s Day perfect game.

Getting There

Since 1993 I’ve gotten to Shea via the Long Island Rail Road, which has had a stop there for Shea Stadium and the World’s Fair since 1964. Before that, though, I came from Bay Ridge, which meant an R or N train (they switched in 1985) to Queensboro Plaza, where a walk across the platform transferred you to a #7, the only such platform transfer (BMT-IRT, or a letter train to a number train) available in the subways. The BMT and IRT jointly operated the Astoria-Flushing Line until 1949, when the Astoria was assigned to the BMT and the IRT took over the Roosevelt Ave el to Flushing.

The MTA will likely have to change the LIRR platform signs to Citifield for the 2009 season. RIGHT: here’s a photo I took of the LIRR platform in 1999 when the old MP50 consists were being retired and were taken around the system for a last fling. Some R33 Redbirds can be seen in the Corona Yards in the background.

The “Passerelle Walkway,” a boardwalk, has transported LIRR customers to both Shea Stadium and Flushing Meadows-Corona Park since the Stadium was opened. It’s still pretty much in the shape it’s always been; even the flagpoles are still in place, without the flags.

Some R62A #7 cars await rush hour on Monday in Corona Yards, over which the boardwalk passes. A few R29/R33/R36 Redbird cars are still in retirement here.

On September 28, 2008 the MTA trotted out its museum car consist on the Flushing Line: R33 WF 9306; R15 6239, R17 6609, R12 5760, R33 pair 9068 (green) and 9069 (redbird red), R33 pair 9010-9011 (MTA blue/silver), R33 pair 9016-9017. Note the 9306: it was been maintained with its original “World’s Fair blue” paint scheme. Most R33’s were later painted dark red for use on the Flushing, Lexington and 7th Ave lines, where they became known as the Redbirds. I wasn’t able to ride the consist on Sept. 28th, but ForgottenFan Gerri Guadagno captured them while they were laid up at Corona.

ABOVE LEFT: Passerelle Walkway in 1964, showing its original lampposts, long vanished. ABOVE RIGHT: another bit of signage the MTA will have to change. They’ve had that tennis racket there for several years; where’s the baseball?

LEFT: The #7 elevated was visible beyond the right field fence. Citifield faces northeast and will not have such a view; I’m not sure if there will be a view at all.

Possibly, 1973 was my favorite year to be a Mets fan. The Mets had been moribund most of the summer, dropping 13 games under .500 at a couple of occasions. But other clubs failed to take charge and the Mets made a run, winning 24 of their last 33 to edge out the Cardinals on the last day of the season. They defeated the favored Cincinnati Reds and took the Oakland A’s of Reggie and Catfish to 7 games in the World Series, and led, 3-2 before dropping the final two in Oakland. Like Gil Hodges before him, manager Yogi Berra made do with magnificent pitching from Seaver, Koosman, Jon Matlack and the unheralded George Stone. Tug McGraw battled a slump most of the year but righted himself down the stretch. Rusty Staub and Felix Millan (.290) were the only consistent bats in the lineup; like 1969, the Mets had to make use of everyday heroes like George “The Stork” Theodore, Jim Beauchamp and Don Hahn. Wayne Garrett had his “career year” with 16 home runs.

On the cover of the 1974 yearbook is the Mets’ 1973 NL Championship banner. I seem to remember the gonfalon hanging on the centerfield flagpole, but perhaps for the cover shot, it was moved to one of the roof flagpoles (these surrrounded the upper deck and held flags corresponding to all National League clubs. I don’t know if the Mets ever followed the Cubs’ practice of showing the flags in order of division standing. For a time in the 1990s, club banners appeared on the outfield fence.For the last several years at Shea, the Mets flew smaller championship banners in right field next to the foul pole.

Also: in 1973 the Mets had a neat trick of spelling out players’ names in large letters on the right field scoreboard. This was long before the days when the board could be programmed to display large letters — the scoreboard consisted of hundreds of squares in which individual light bulbs were lit to produce letters and numbers. So, the scoreboard operator lit up several entire squares in a sequence that would produce large letters, as you see above.

My Favorite Uniform

Note Felix Millan’s uniform styling, photo above. In the early 1970s the Mets had arrived at my favorite uniform in their 46-year history. They were still using pinstripes at home, and road grays with NEW YORK arched across the chest (they returned to this in the 2000s) and pants had arrived at the optimum length, with stirrups and white sanitary socks in just the right proportion: about 60% white, 40% color. These days, pants and socks stylings are completely wrong; guys wear either bell bottoms that bunch around the ankles, or hike the pants to the knees with unicolored socks without stirrups. Either way, they look like clowns. Were I league president I would mandate that the players return to the uniform style Felix Millan used here.

Note the Braves’ Dusty Baker in Atlanta’s early 1970s dark blue uniform with the stylized feather on the shoulder. This is the uniform style worn by Hammerin’ Henry Aaron when he broke Babe Ruth’s lifetime home run record in 1974. The Braves would change to the retro Milwaukee Braves “tomahawk” uniforms in the 1987 season.

1974 is probably my favorite Mets’ yearbook in my collection, with plenty of photos, unavailable anywhere else, of the Mets’ playoff and World Series run. The yearbooks produced by the Mets in the 1960s until the end of the 1970s were terrific blends of photography, design and writing. The matter-of fact prose style used for the Mets’ biographies in the yearbooks of that era, which all read as if written by the same person, actually greatly influenced the style I use when writing Forgotten New York.

The Zipper Factory

Throughout most of Shea Stadium’s existence (except for the last couple of years, when Citifield was being constructed) a large, four-sided clock tower was visible beyond the left-field fence. This was the Serval Zipper Factory, latterly a U-Haul distributorship. The clocks, of course, stopped long ago.

Unfortunately, I don’t have a good picture of it from beyond the Shea outfield fence, but here are views from the Passarelle Boardwalk (above), King Road in Flushing, and from the Iron Triangle across the Flushing River. The structure was originally the Queens office of W & J. Sloane Furniture Co. on Lawrence St. (now College Point Blvd.) in Flushing.

Throughout Shea Stadium’s existence there was a walkway that took pedestrians from the #7 token booth area over the parking lot roadway and Roosevelt Avenue to the ballpark. Till the end, it retained its three-headed mercury-bulbed lampposts (right, seen in August 1965 when the Beatles played Shea). To facilitate Citifield construction it was demolished in 2007 and a walkway that took patrons downstairs to the street was constructed (left). I’m not sure whether it’s temporary or permanent. photo right: baseball fever