guest post by DON GILLIGAN

On March 1, 1932, 77 years ago (in 2009), at about 9:00 PM, someone placed a homemade ladder against the wall of the Lindbergh home in Hopewell, NJ and set in motion a series of events that would culminate three years later in a trial that journalist H. L. Mencken would call, with characteristic hyperbole, “The greatest story since the resurrection.”

The kidnapper ascended the ladder, entered through an unlocked, second story window, removed twenty month old Charles Lindbergh, Jr. and left behind a ransom note demanding $50,000. The note was “signed” with a symbol consisting of two intersecting circles, a red mark and three punched holes, which would serve as the authentication code of future communications.

Although the kidnapping took place in New Jersey, many of the ensuing events took place in the Bronx. Two of the principals in the case were Bronx residents. Bruno Richard Hauptmann, the man who was convicted of the crime, lived at 1279 East 222 street. John F. Condon (Jafsie), who acted as go-between for Lindbergh and delivered the ransom money, lived at 2974 Decatur Avenue (left). Both houses still exist in much the same form they had when Hauptmann and Condon lived in them.

ABOVE, former home of Richard Hauptmann, 1279 E. 222nd Street at Needham Avenue.

Other locations, such as the cemeteries where Condon met with Hauptmann to negotiate and pay the ransom, the bakery on Dyre Avenue, where Hauptmann claimed he was picking up his wife when the kidnapping took place, and the Bronx County Courthouse, where Hauptmann was indicted for extortion, which allowed authorities to hold him until his extradition to New Jersey to face the more serious charge of murder, still exist as well.

Condon became involved in the case when his letter to the Editor of the Bronx Home News was published in that paper. Condon offered to add $1,000 of his own money to the ransom money “…so a loving mother may again have her child.” It was probably a grandstand play, but much to his surprise he received a letter from the kidnapper. It contained an enclosed letter addressed to Lindbergh. That letter had the same authentication symbol as the original ransom note. When Lindbergh saw it, he authorized Condon to act as go-between and paid several visits to Condon’s home during the ransom negotiations.

Condon devised a code name, Jafsie, from his initials: J.F.C., and used it in classified ads placed in several NY newapapers to communicate with the kidnapper. A late night face to face meeting was set up along side Woodlawn Cemetery on this lonely stretch of Jerome Avenue. A man who Condon later identified as Hauptmann, spoke to him from inside the cemetery. Not much was accomplished at the meeting as a cemetery nightwatchman interrupted the meeting.

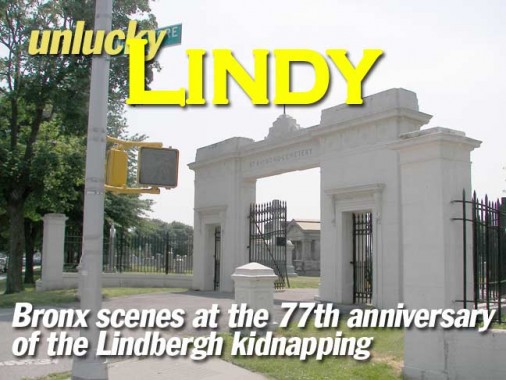

After further negotiations, Condon delivered the ransom to “Cemetery John” during another nighttime meeting in St. Raymond Cemetery. The ransom was delivered at the corner of Whittemore Avenue and a cemetery service road. In exchange Condon received a note which stated that the baby was “on the boad [sic] Nelly” off the Elizabeth Islands near Cape Cod. The boat was never located. A few months later the baby’s remains were found in the woods less than two miles from the Lindbergh home in Hopewell.

Looking down Whittemore Ave from near corner of Tremont & Whittmore. The service road into the cemetery is located where the concrete wall ends. The two people standing by the chainlink fence are just a few steps away from where the exchange took place. RIGHT: entrance to the cemetery at the corner of Tremont and Whittmore Aves. The ransom was delivered about 100 yds down Whittmore Ave (to the right in the picture).

Hauptmann’s downfall came about when he used a ten dollar bill from the ransom money for a gas purchase in Harlem. The bill was a gold certificate. The gas station attendant, worried that the ten might be counterfeit, wrote Hauptmann’s license plate number on the bill. When the ransom payment was assembled, the Treasury Department, knowing that gold certificates would soon be withdrawn from circulation, had loaded the payment with gold certificates. The serial numbers of every bill in the ransom payment were recorded and distributed to banks nationwide. A sharp eyed bank clerk who processed the gas stations deposit spotted the gold certificate, checked the serial number and called the police who had no problem locating Hauptmann. He was found to have another bill from the ransom money on his person when he was apprehended.

Hauptmann, a carpenter and illegal German immigrant with a criminal past, lived with his wife and infant son in a rented apartment on the second floor of this house on the corner of 222nd Street and Needham Avenue (above). He kept a car in a garage that he built across Needham Avenue from where he lived. While the house still exists, the same may not be said of the garage. It was reduced to splinters during the NYPD/FBI search and recovery mission that turned up over $13,000 of the ransom money.

During his trial Hauptmann claimed that, at the time of the kidnapping, he had gone to pick up his wife at Frederiksen’s Bakery on Dyre Avenue in the Bronx where she worked until nine o’clock on Tuesdays. Unfortunately for Hauptmann, when Frederiksen testified, he said that he could not remember if Hauptmann came to the bakery on that particular night. The bakery still exists. It has passed through numerous owners since that time and is now a Caribbean bakery.

Hauptmann also claimed that the money came from a package that had been given to him for safekeeping by Isidor Fisch, a former business associate, who had gone to visit his family in Germany. He further claimed that, while stored in a closet, a roof leak had caused the package to open revealing the money inside. Hauptmann claimed that since Fisch owed him money, he felt entitled to use some of the money from Fisch’s package. Fisch, at this point, was conveniently dead, having succumbed to TB while in Germany.

The final nail in Hauptmann’s coffin was testimony that one of the side-rails of the homemade ladder was made from a floorboard removed from the attic of the house where Hauptmann lived. Nail holes in the board aligned perfectly with nail holes in the attic floor joists and the wood grain at the end of the board aligned with the piece of board that remained on the floor after the ladder piece had been sawn away.

Because Hauptmann pled not guilty at his trial and steadfastly refused to confess even when the Governor of NJ offered to commute his death sentence to life imprisonment, there are people to this day who maintain that he was innocent. That website maintains that Hauptmann was railroaded, mainly I think because the person or persons who maintain the site have an anti capital punishment agenda. They also devote a page to Richard Sloan, the guy who conducts an annual Lindbergh Tour (for a fee). His tour covers the Lindbergh case in a lot more detail than this summary. You might get the idea from the way they present Sloanís tour that he agrees with their position but I took the tour and can say that Sloan is impartial.

The definitive book on the Lindbergh case was written by a former FBI agent: The Lindbergh Case by Jim Fisher, Rutgers University Press, 1987.

Page completed March 5, 2009; text and photos by Don Gilligan.