As Forgotten New York begins its second decade (and at your webmaster’s age, I hope there are a a few more decades to go) I lined up something extra special that I didn’t think I would be able to do without a lot of walking and climbing — an exploration of the old Long Island Rail Road’s so-called Bay Ridge Branch, which runs from Glendale’s Fresh Pond Yards southwest, south, and west through Ridgewood, East New York, East Flatbush, Midwood, Parkville and Bensonhurst to its finale at the 65th Street Yards at the Brooklyn Army Terminal where the Narrows widens into Upper New York Bay. The trip was possible via the efforts of Joel Torres, Chief Transportation & Commercial Officer of the New York and Atlantic Railway, a longtime ForgottenFan who offered to pilot an engine down the now-little used road all the way from Fresh Pond to Bay Bay Ridge.

Fresh Pond Yards

Normally inadmissible for railfans, passing strangers or Forgotten bloggers, Fresh Pond Yards is a combined MTA-New York and Atlantic-Long Island Rail Road yard servicing the MTA’s Nassau Street-Ridgewood Line (the M train) as well as freight operations. The station is located at a junction in Glendale Queens south of Lutheran-All Faiths Cemetery, with offices accessible from the entrance on Otto Road and 68th Street. The yards and the nearby Fresh Pond Road are named for a former fresh water pond that was filled in decades ago; fresh, in contrast to salty or brackish, as several ponds in the area also could be (Fresh Meadows in eastern Queens is named similarly).

Besides the generous sprinkling of engines, freight cars and tankers in the NY & Atlantic RR section of the yards, the truss bridge that connects the NY Connecting Railroad at the west end of the yards is a prominent landmark (the NYCR was the site of a walk sponsored by the Electric Railroaders Association, New York Division a few years ago, covered here by FNY). Canadian Pacific and CSX freights generally make the NYCR run during the week, hauling freight from the Oak Point Yards in Hunt’s Point, the Bronx, crossing the Hell Gate Bridge, though there are occasional runs by the Providence and Worcester as well. Some mail trains run late at night.

The New York and Atlantic, meanwhile, has been the freight arm of the Long Island Rail Road since its formation in 1997. It employs LIRR passenger line tracks (where it operates mostly at night), via carfloat in association with the NY ross Harbor Railroad, and using the NY Connecting Railroad to the mainland via the Hell Gate Bridge — as well as today’s route over what is now known as the Bay Ridge Branch. Lumber, building products, scrap metal, construction & demolition debris, food, beer, gravel, propane, chemicals, structural steel, plastics and recyclable cardboard/paper are NYA’s main traffic. Most of the engines are LIRR rolling stock, including today’s train, Engine 151, freshly painted in green, black and white NYA livery. information via wikipedia

The Manhattan Beach

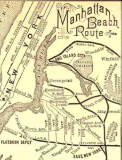

LEFT: 1884 map, Manhattan Beach line; right: 1900 map. arrts arrchives

What is now called the Bay Ridge Branch is the remnant of a former passenger and freight line that connected to widely dispersed points in Brooklyn and Manhattan. At one time, over a century ago, it was possible to ride by ferry from 34th Street and the East River, catch a train in Long Island City and take a one-seat ride to the salty breezes of Manhattan Beach; or, if you wished, you could change trains at East New York and head west to downtown Brooklyn, or at het another transfer point, to Bay Ridge. The New York, Bay Ridge and Jamaica Railroad was formed in 1876 and ran on tracks on the surface, or at grade, to a junction of the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad at today’s New Utrecht Avenue.

Meanwhile, railroad pioneer Austin Corbin had incorporated the NY and Manhattan Beach Railway on October 24, 1876 and acquired the NY, BR & J the following month. Corbin moved quickly and extended the line to New Lots in 1877 and Greenpoint in 1878, along today’s defunct Evergreen Branch. (also see Art Huneke’s Evergreen pages). The merged Long Island City and NY, BR & J became the New York, Brooklyn and Manhattan Railway in 1883 and built out to Glendale in 1883. While the early days of the route saw busy passenger traffic, the line began to falter in the early 1900s, and passenger service ceased altogether in 1924; it was never referred to as the Bay Ridge Branch while in passenger service, but rather the Manhattan Beach, which saw the bulk of fares during the summer. The road ran with steam locomotives early on, but was electrified for freight in 1927. Electric service ended in 1968 and diesel powered trains have been on the road ever since.

The Journey Begins

As Joel Torres took Engine 151 out of Fresh Pond Yard we were met almost immediately by the junction with the NY Connecting, marked by the only large railroad signal tower we saw on the road. THis connection allows trains proceeding eastward from Bay Ridge to cross the Hell Gate Bridge onto mainland USA. RIGHT: crossing Cypress Hills Street over a viaduct. This road, though it attains only four lanes at its widest, is a main route between Ridgewood and Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, as it crosses Queens’ Cemetery Row. On either side, it passes Mt. Carmel, Beth-El, Machpelah (the final resting place of Harry Houdini), Mt. Neboh, Mt. Carmel, B’nai Jersualem and Shearith Israel, Salem Field and Cypress Hills cemeteries, and can transfer traffic to the Jackie Robinson Parkway.

It must be emphasized that most of our route was on an elevated trestle (eastern portion) or open cut (western portion). As Brooklyn and Queens became more populated in the early 20th Century, the line’s grade crossings were eliminated, mostly between 1905 and 1915. Grade crossings are few and far between in NYC, but there are still some around.

A closer look at the ruined signal tower. We would see smaller ones as we progressed. Also notice the struts that held catenary wire that powered the route in its electric era. Very little trace of them remain along the road.

The Manhattan Beach operated a stop at Myrtle Avenue between 1893 and 1924. Though the stop featured side platforms, there is a surviving concrete island between the tracks.

The station survived a grade crossing elimination in 1914 (left, looking north on Myrtle Avenue). arrts arrchives

Myrtle Avenue, named for myrtles that formerly grew in its vicinity in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, was constructed as a plank road from the downtown Brooklyn area out to Jamaica in the 1850s. If you look at a map, it cuts across the NE-SW oriented Ridgewood street grid, which was built after the road was extended through.

We passed a factory that formerly had a siding to accept freight before passing another former station at Cypress Avenue, above right. The station was in operation between 1883 and 1924, and was grade-eliminated in 1914.

You pass a large number of dead people along the Bay Ridge, as the road borders Evergreens Cemetery, a.k.a. Cemetery of the Evergreens, which would be Brooklyn’s second-largest cemetery were it not about equally divided between Brooklyn and Queens. (Indeed, some may be buried with their heads in Brooklyn and feet in Queens, or vice versa.) The cemetery is the final resting place of cartoonist Winsor McCay of “Little Nemo” fame, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and filmmaker/actor John Bunny. You will also find a memorial to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory disaster victims here. The cemetery was incorporated in 1849 and is the subject of a new coffee table book.

Above right: Just past Wyckoff Avenue is the junction with the old Evergreen Branch route (see links above on this webpage). The tracks were in greater evidence when I first began surveying them in the 1990s but today most signs of the branch have been eliminated; a clearing by the side of the tracks indicates the junction in 2009.

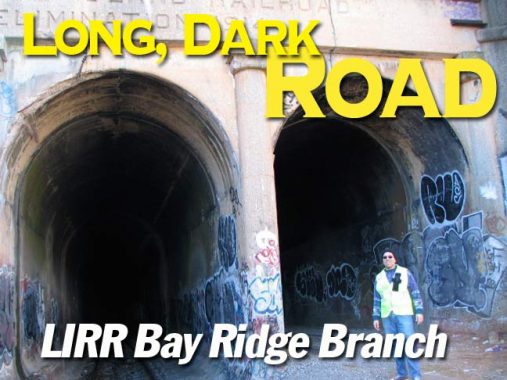

The Perfect Tunnel

The Bay Ridge is joined here by the BMT Canarsie Line (the L train), which will parallel it as far as the old New Lots station (below). At the tunnel entrance, graffitists have had a clear shot over the years as about 4-6 freights use the line here daily.

The tunnel boasts a near-perfect roof vault; the portals resemble upside-down capital U’s. Unlike other NYC railroad tunnels, this one is unlit and I doubt it ever was. The interior is barren of graffiti, as it is pitch black and I’m not sure if graffitists want to run the risk of an NYA loco bearing down on them as they work. The runup to the light emanating from the south end of the tunnel is exhilarating. The trip from the birth canal to the operating room must look like this. No one remembers it though.

Emerging into the light just south of Atlantic Avenue, we have arived at the East New York platform, which still exists.

The only remaining platform from the old New York and Manhattan Beach, East New York was in passenger operation from 1877-1924, with this concrete center platfom in use beginning in 1915. It was in use for between just 8 and 9 years before service was eliminated! Note the trolley (or is it a diner?) on Atlantic Avenue over the tunnel entrance. Ron Ziel collection

In photos above, the Canarsie Line, which paralleled the Manhattan Beach until the late 1910s, runs on a trestle built high to bring it over the now-vanished Fulton Street el. Here, the Canarsie has a flyover to connect it with the Broadway Line; this has not been employed in passenger service since 1968.

Though there are several rights-of-way ripe for the plucking to allow greater transit outreach to several underserved neighborhoods (such as the ruined LIRR Rockaway Branch) one unwritten rule of New York’s transit agencies over the years has been “taken out of service, never put back in.” This rule even extends to line identifiers — the H, once an IND shuttle to the Rockaway peninsula, the K — once the Eighth Avenue local (now the C) and even the #8 train (once the IRT Bronx Third Avenue el) have never been used again! In 2009, the MTA will likely retire, for good, the W and Z designations.

The East New York transit interchange — which connects the 8th Avenue – Fulton Street line (A, C) with the Broadway line (J) and Canarsie (L) — could be even better if the old Bay Ridge tracks could be activated for passenger service across town to Bay Ridge. But, even in times when the MTA is not millions in debt, it would never revive the line and so the NYA will likely have unlimited dominance for years to come. But railfans can dream. There was a time when trains were actually built to the middle of nowhere because real estate developers were sure to enter any area with good mass transit.

The East New York platform, while not in use for over 85 years, is occasionally fitted to double as a subway platform for TV shows such as “Law & Order.” A paint job for a TV show on the pillars is still in evidence. RIGHT: a close look at the roof reveals girders that support the Long Island Railroad under Atlantic Avenue. This branch is very much active, bringing trains to and from Flatbush Avenue. Its own East New York station can be seen on this FNY page.

UFO and other graffitists have tagged the ENY platform repeatedly. RIGHT: the Stygian tunnel, seen extending north toward Ridgewood.

As we move south in East New York, the Bay Ridge travels in an open cut while the Canarsie Line is on an overhead el along Van Sinderen Avenue, which long ago was called Vesta Avenue, after a minor goddess in Roman mythology. Just south of the New Lots L train station, however, both lines parallel each other at grade and we can see a now-cutoff interchange track between the two. As recently as about 15-20 years ago this track connection could be used to transfer LIRR units onto BMT trackage. It was never used this way, however; new cars could be brought on to BMT tracks using this method. Nowadays the transfer is made in Fresh Pond Yards or Coney Island Yards via the Cross Harbor Railway.

In the distant past, however, LIRR trains could and did use BMT tracks: there was a flyover that connected the LIRR with el tracks along the el on Fulton Street in the vicinity of Cleveland Street, and LIRR units then used the Broadway Line across the Williamsburg Bridge to a terminal at Chambers Street, which also formerly served the Manhattan Bridge. LIRR service across the Williamsburg ended in 1913, and the Chrystie Street track realignment in 1967-68 ended Manhattan Bridge service to Chambers.

The Manhattan Beach had a station at New Lots Road, now named New Lots Avenue, from 1877-1897. No trace exists now since the grade crossing elimination program wiped it out.

Strictly speaking, the station was between New Lots Road and Hegeman Avenue, a Brooklyn street I have no idea to pronounce without speaking to any of the locals to find out how they say it. I did this withLuquer Street and found more than one result.

In the colonial era, New Lots was settled several years after Flatbush was by Dutch immigrants. After all fields in Flatbush were claimed, several families moved east into untilled land, calling the new fields New Lots, in contrast to the old lots in Flatbush.

After crossing over 6-lane Linden Boulevard (the six-lane section runs from Kings Highway to the Belt Parkway; Linden Boulevard proper runs in pieces from Flatbush Avenue to Elmont, Long Island) the Bay Ridge turns southwest and runs past the Linden Yards, where new rail ties and rails are delivered. I did see some older cars laid up in the yard: can anyone ID them?

ForgottenFan James Hynes: these were R-17 cars numbered 6813 and 6850, they were used to carry continuously welded rail.

We crossed Rockaway Avenue: three of NYC’s five boroughs have numerous streets that trace their name to theReckowakie, the “place of our own people” of the Canarsee Indians, as does a thin peninsula on the Atlantic Ocean in Queens, a Nassau County village, and a New Jersey township.

SW of Rockaway Avenue, at approximately East 92nd Street, lay the Ford’s Corners station, later renamed Rugby as part of a local real estate development. The Ford’s Corners name to this area has vanished completely. The station was in operation from 1888-1924 and survived the grade elimination program.

Beginning here and continuing west were the first of many homeless settlements, complete with berbecue grills (below left). During the week there are about 6 trains per day that travel slowly along the garbage-strewn trackways.

West of Ford’s Corners we came upon the switch that connected to the tracks leading to the Brooklyn Terminal Market, where the Bay Ridge makes numerous deliveries. ForgottenFan Vinny was our designated switcher for the day and after he did the honors, we descened on a hill steep by diesel powered standards (careful braking is necessary) we arrived at the market.

Dedicated by the late Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia, the Brooklyn Terminal Market opened for business in 1942. Located on Foster Avenue between East 83 and East 87 streets, the market has earned a fabulous reputation for offering excellent quality at great prices. In fact, after 66 years of both retail and wholesale business, the Brooklyn Terminal Mark had virtually become a Canarsie Landmark. Brooklyn Terminal Market Online

After climbing the hill and switching back to the Bay Ridge, the NYA 151 crossed Remsen Avenue (left) and Ralph Avenue, which join Rockaway Avenue and Parkway as the 4 big R’s in East Flatbush and Canarsie. Oddly, Rockaway Parkway, which is a good 4 lanes with a center median from East New York Avenue to the Rockaway Pier in Canarsie, dead ends at the railroad — traffic must detour on Linden Blvd. and Rockaway Avenue to go further south. Remsen Avenue is named for one of the many Dutch settling families in the colonial era; oddly, Ralph Avenue takes its name from someone’s given name, Ralph Patchen, an early 19th Century farmer in what became Brooklyn Heights. There is a paralleling street, Patchen Avenue, in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

A prominent client of the New York and Atlantic RR is Manhattan Beer Distributors, a major supplier of the Coors and Corona brands. The wholesaler has a spur leading to its warehouse.

Kings Highway. Though it now extends from Bay Parkway in Bensonhurst southeast and northeast to East 98th Street in East New York, the road, which has its origins as a Native American trail in pre-colonial times, is much shorter than it once was; it once counted much of Fulton Street as much of its length from the East River to Flatbush Avenue, and Flatbush Avenue itself is part of its network of old roads. In addition it once extended west to a location that today is the corner of Ft. Hamilton Parkway and 86th Street in Bay Ridge. For most of its existence, it was a simple one-or-two lane country road, but in the early 1920s Borough President Edward Riegelmann recognized its potential importance as a SW-NE route as it defied the street grid, and from Ocean Avenue to East 98th, it was rebuilt as the familiar multi-lane behemoth it is today. West of Ocean Avenue it developed into one of Brooklyn’s busiest shopping streets, and eventually, the Del Rio Diner was built at Kings Highway and West 12th Street, where our post-trip meal was located today.

The location of diners is very important in the history of any street worldwide.

Kings Highway east of Flatlands, until Brooklyn’s consolidation with the rest of NYC, was known by several names, including the somewhat unwieldy “Road From Flatlands to New Lots.”

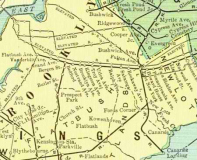

Kouwenhoven Station sat at approximately Kings Highway just south of Foster Avenue and was in existence from 1877-1924.

ABOVE: at-grade Kouwenhoven Station with shed, approximately 1905, from the collection of LIRR historian Ron Ziel. The road that is planked over the railroad is today’s pedal-to-the-metal Kings Highway, then called the Road From Flatlands to New Lots. The road and station are shown at left in a 1890 Kings County atlas when this was part of the Town of Flatlands. As you can see, Gerret Kouwenhoven owned the surrounding land.

Note the “E” and “F” on the planned streets at top and bottom. These are today’s Foster Avenue (Avenue E) and Farragut Road (then Avenue F).