I am fond of speculating about possibilities that I will never experience. In future centuries, if we don’t snuff ourselves, there is going to be quite the sightseeing market on those satellites that orbit the bigger planets in the solar system. Imagine the view of Jupiter, with its swirling clouds and red spot (you can drop a few planet Earths in it) that can be had from Europa or Ganymede or any of the innermost of its 64 moons; or the sight of Saturn’s rings that can be had from Enceladus or Tethys. I’m reminded of looming planets in the sky by the sight of the vast concrete arches that allow streets to pass beneath the tracks taking passenger and freight trains across the Hell Gate Bridge, the magnificent arch bridge completed by master bridge builder Gustav Lindenthal in 1917. You don’t see a lot of photos of them, and on a recent trip to Astoria, there is definitely some Forgotten material rattling about under the arches.

From FNY’s From Penn Station to Astoria page: The Hell Gate Bridge was the final piece in the puzzle of running railroad trains into Midtown Manhattan. The tubes connecting Long Island with Penn Station opened in 1910, and _Hell Gate Bridge, connecting Long Island with the mainland, opened in 1917 as the lengthiest steel arch bridge in the world until surpassed by the Bayonne Bridge in 1931. “Hellgat” means ‘beautiful strait” in Dutch, but lived up to its English transliteration as an extraordinarily dangerous stretch of water due to conflicting currents of the East River and Long Island Sound, as well as a great deal of rocks that made it treacherous for shipping until the rocks were dynamited into rubble in the late 19th Century. The construction was overseen by Gustav Lindenthal, who worked on the Williamsburg and Queensboro bridges as well. In the mid-1990s it was painted a deep maroon, which the sun has faded to light magenta.

ABOVE: Concrete support arches in Astoria Park (left) and Ward’s Island (right).

Sharon Reier in The Bridges of New York: The 1,017-foot long arch, of course, is only the keystone is a system of water and land crossings that in itself was the largest of its type in the world. The whole length of the structure, including the arch and approaches from the abutment on Long Island to the abutment in the Bronx is 17,000 feet, or considerably more than three miles…

….few people, even passing as close to it as the Triborough Bridge, realize the colossal size of the various parts. No existing large span bridge had ever been designed with such huge parts. Some of the steel members were more than twice as heavy and bulky as any parts ever hoisted in previous bridge construction… The heaviest bottom chord section weighed 185 tons. They were made of a recently developed material — carbon steel — which gave greater strength for its weight. The bridge, it was said, used more steel than the Manhattan and Queensboro Bridges combined.

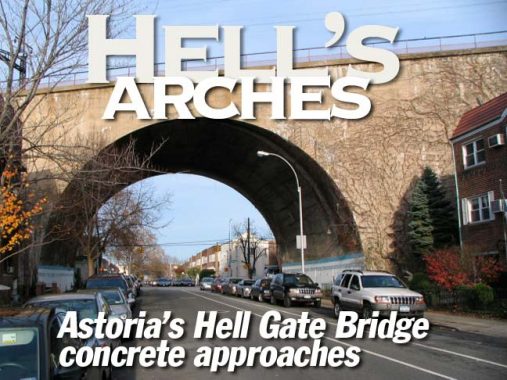

I have always admired the step and repeat nature of the concrete arches that take the steel structure to and from the arch, located in Astoria and Ward’s Island, and also a feature of the Hell Gate that has always been little remarked upon: the massive arches that take the railroad over 29th, 31st, 33rd, 36th, 37th and 38th Streets. The railroad tracks are built on a massive, concrete-supported embankment in much of its route in Astoria, and a combination of iron trestles and concrete arches span the streets beneath.

RIGHT: locations of Astoria’s Hell Gate Bridge arches are marked in red.

29th Street (formerly Singer Street) seen from 23rd Avenue (Potter Avenue). As you’ll see this arch is rather narrower than the others — since 29th Street is no narrower than its parallel streets, I can’t acount for why. It’s likely that the frame and brick houses came along after the massive structure was built between 1914-1917. The steeple in the distance on the right belongs to the Immaculate Conception Roman Catholic Church on Ditmars Boulevard.

31st Street

31st Street (Debevoise Avenue) – along with 21st and Steinway streets, the main NE-SW arteries in Astoria. Since 1917, 31st Street has been overshadowed by the elevated trestle of the Astoria Line — a momentous year in NYC transit, as many elevated lines were completed that year, and passenger trains for the first time could run from Penn Station north through Astoria, over the Hell Gate, and into New England.

For several years, the concrete embankment has been shadowed by scaffolding here, as a rehab and repainting project is under way. The best view of the arch can be had from the Ditmars Boulevard platform in this NYCSubway.org vintage photo (1976). The cars are vintage R10s.

Ditmars Blvd. is the Astoria line terminal, and in your webmaster’s view, the IRT/BMT as well as the Pennsy missed the boat in not providing a passenger station/connection here.

33rd Street

23rd Avenue’s buildings and storefronts cluster together against the onslaught of this vast interloper — or do they depend on it for protection?

The 33rd Street Arch is the only one to have significant art inscribed on each side. This now fading mural was likely done just before the 2004 Olympic games in Athens, Greece; Astoria has long been a Greek American stronghold.

The east side of the arch features some bizarre imagery; the panels, collectively called “We Need A Hero” was collaborated on by PinkSmith and students from the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts (located in the nearby Kaufman-Astoria Studios) and was completed in 2007.

A closer look at the intersection

Proving once again there are curious things rattling about under NYC overpasses, an old school pull handle fire alarm in a new 1960s-era alarm stanchion; these began to replace the 1910s “ice cream cone” alarms beginning in the mid-1960s. Most now have red and blue police and fire alarm call buttons. LEFT: now-decommissioned Westinghouse AK10 ‘cuplight’

Massive riveted support pillar. Lindenthal foresightedly designed the Hell Gate and its approaches to bear much more weight than it currently does, thinking that railroad trainsets would only get bigger and heavier. As it is, the Hell Gate is one of the most underutilized bridges in the city; why not add local transit and build some local stations in Queens and the Bronx? $$$$$$, that’s why. RIGHT: very old rusted sign, Sunnyside Prints. We’re a few miles from Sunnyside, actually.

Our railroad embankment dips south of 23rd Avenue at 36th Street (the erstwhile Blackwell Street). Vines grow against the arch; I wonder if these still get green in the spring. An effluvium, an ichor, drips from several openings in the concrete wall, likely from a nameless miasma in the depths of the embankment. (I think I’m reading the Newtown Pentacle too much.)

We have seen before that unusual survivors cling to NYC underpasses, and the 36th Street Arch is no exception; illuminating the sidewalk, once upon a time, was a 1910s-era scrolled stanchion usually found mounted on telephone poles. It likely ran through more than one luminaire; a radial wave lume was likely the first one. Sometime in the Fab 40s or 50s, a Westy cuplight was grafted on, but as you can see, relentless oxidation has consumed it.

Doubling back to 23rd Avenue to proceed to our next Arch, your gaze becomes rapt by the Greek Orthodox St. Irene Church, known more properly as the Sacred Patriarchal & Stavropegial Monastery of St. Irene Chrysovalantou. The story of St. Irene (who was quite the looker from her portraits) can be found here.

Located in Astoria, New York, St. Demetrios’ Cathedral (at 31st Street and 30th Drive) and St. Irene of Chrysovalantou serve one of the country’s largest and strongest Hellenic-American communities. As part of the Greek Orthodox church, these cathedrals continue in the traditions set forth by the seventh ecumenical synod (Nicea II, 787 C E), through which the use of icons in the liturgical practices of the Eastern Church was legitimized.

The reason there were two cathedrals is a dispute within the Greek Orthodox Church about the use of the Julian vs. the Gregorian calendar. St. Demetrios is the Cathedral of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese. America, which uses (for the most part) the Gregorian calendar. St. Irene [completed in 1972] belongs to a group which broke away over this issue. However in May 1998, the group at St. Irene were reconciled with the main Orthodox church, and at ceremony presided over by the _Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople the Cathedral was converted to a “patriarchal and stavropegial monastery”. Fordham University

One of Astoria’s many handsome apartment buildings greets us at 37th (Pomeroy) Street and 23rd Avenue. Multifamily housing used to be rendered with flair and panache –wonder how they forgot to do that.

The 37th Street Arch is quite similar to its partner on 36th Street, but here we see some evidence of wear and tear on the over 90-year-old structure, as concrete has worn down enough to expose the supporting iron rods.

The 37th Street Arch as two remaining sidewalk illuminators, one on each side. Note that the luminaire connection is subtly different from one to the other.

I’m quite tempted to do a full page on NYC’s fire alarms — the oldest designs still found on street corners go back to 1913 or so, and there are still a multitude of styles out there–it’s a glorious mishmosh. This one originally had a fire alarm light, originally red glass, at the top of the pipe, which has since been adapted to connect with power lines above. This one has a second generation pull handle. LEFT: houses on the south side of 23rd Avenue have a great concrete wall view.

At 38th (Kouwenhoven) Street and 23rd Avenue is a handsome brick structure, once part of the Astoria Silk Works (once owned by Col. Jacob Ruppert before he purchased the New York Yankees in 1914), now in part occupied by dance and recording studios.

The 38th Street Arch has crumbled sufficiently enough that Amtrak has had to shore up the arch with a metal superstructure.

East of 38th Street the railroad is again carried on a stout carbon steel trestle across Steinway Street, over Grand Central Parkway and then south and west into the Sunnyside Yards complex. New York Connecting Railroad tracks continue south to Fresh Pond Yards, where freight connection can be made with the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch. Meanwhile, Amtrak trains continue on to Penn Station via the East River tunnels. A couple of additional arches can be found on the side streets north of 25th Avenue: these can be seen on FNY’s NY Connecting Railroad page.

Page completed November 22, 2009