A few weeks after my trip to Far East Williamsburg, I had a hankering for roughly the same territory, but this time, a little further west, where there is somewhat more of a human presence. I settled on walking down Manhattan Avenue and up Graham, in what is mostly east Williamsburg, though not far east, and at the end of the route, a bit of Greenpoint. I have seen much of Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint proper already, so on this occasion I pressed south into a location I haven’t often been in — a classic FNY journey. It was one of those days of high overcast, eliminating shadows, but since it was December, lighting was still a bit of a problem. I amended a lot of the pictures in Photoshop, risking a washed-out look; I’m no photo snob, and will issue no apologies for perceived amateurishness, not that I get any. (I’m not a fan of photo technique snobs.)

WAYFARING: MANHATTAN and GRAHAM AVENUES

Let me begin by saying that, as a native Brooklynite (those who know me say I have something of a midwestern accent; I carefully try to excise any Brooklynishness from my vocal, since I’ve always wondered what New Yorkers in general have against a final “r” in words — it’s not “cah”, it’s “car”) I protest the notion of a Manhattan Avenue in the first place.

Manhattan Avenue, like its parallel routes in East Williamsburg and Greenpoint, runs according to house numbers from Broadway (just north of Flushing Avenue) north and northwest to Newtown Creek. Until about 1886, Manhattan Avenue, or rather the route it would eventually follow, was known as Ewen Street (for 19th Century city surveyor Daniel Ewen) from Broadway to about Richardson Street; Orchard Street, from Van Pelt (now Engert) Avenue north to Greenpoint Avenue; and Union Avenue (in the colonial era, Hill Road), the rest of the way. In 1886, Union Avenue and Orchard Street had become Manhattan Avenue, which, at the time, remained separate from Ewen. In May 1897, the entire stretch became Manhattan Avenue; att that time Daniel Ewen became lost to memory, as far as a NYC street name remembrance goes.

In 1909 the City created a large, rambling park on the Greenpoint-Williamsburg border, between roughly Nassau Avenue, North 12th, Bayard, Leonard, Lorimer Streets and Driggs Avenue, naming it McCarren Park after a just-deceased, prominent local state senator. The creation of the park gave City engineers a chance to re-jigger the street layout, and Manhattan Avenue to the north was united with the old Ewen Street section, creating a direct north-south route, and Manhattan Avenue as we know it was created.

My objection? In your wildest imagination … would there ever be a street named for Brooklyn on Manhattan Island? Some Manhattanites rarely visit Brooklyn or any other borough, and are proud of the fact. What’s more, in Brooklyn voted for consolidation with Manhattan by a mere 200+ vote margin — were it not for those 200+ votes, Manhattan would still have a rival across the mighty East. Why should we honor such a traditional enemy?

I have to control myself. In Forgotten NY, no one borough is the other’s superior; but I have to restrain myself at times.

Manhattan and Nassau Avenues, where I began my trip. Bedford Avenue* begins a long route south to Sheepshead Bay here, as well.

Simon’s Tool and Industrial Supply still has its venerable plastic-lettered sign. The bishop crook posts are modern versions installed in the mid-1990s.

*FNY has covered two-thirds of Bedford Avenue, from Sheepshead Bay north to Fulton Street, and the northernmost section is in prep.

The New Warsaw Bakery, between Nassau and Driggs, is a baked goods wholesaler; it extends through to Lorimer Street.

Manhattan Avenue is the eastern end of McCarren Park from Driggs Avenue south to Leonard Street.

Though the SE corner of Driggs and Manhattan is home to a multi-story condo tower (taking advantage of the park view), I’ll show you the two old-school buildings on the NW and NE corners. A great deal of craft went into the exterior construction, with window lintels, corbelled facades, and differently-shaped windows. Bridge and Tunnel Club provides a look at the interior of Enid’s, a “chicken fried chicken” restaurant.

One of the region’s new residential towers, Manhattan and Engert Avenues. Many sem to have been built using the same color palette: gun metal gray. They’re a step above Queens’ new rusted-terraced, concrete-lawned Fedders Specials, but just.

At Manhattan Avenue, Leonard Street and Engert Avenue is the rear entrance, or what presumably will be, to the rebuilt McCarren Park Pool. The pool, constructed in 1936, was the final of eleven great swimming pools built in NYC in the 1930s; after it was closed in the early 1980s, it lay unused for over two decades (as recorded on FNY’s McCarren Park Pool page, written in 1999). From 2006-2008 it was a prime concert venue, hosting bands such as the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Wilco and Sonic Youth. In 2009, work began that would completely restore it as a neighborhood public swimming pool, in the Astoria Park Pool model. In fact, the bulldozers arrived the very day I walked past.

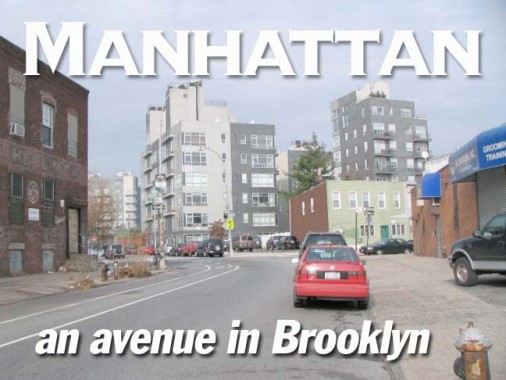

427 Manhattan Avenue at Bayard. This building was at one time used for manufacturing or warehousing, and it now stands starkly on the edge of the region’s new residential towers (see title card, above). As for the artwork, I, too, would have liked to get Monroe, Presley, Norris, and Obama at a big round table for a discussion. Alas, it can’t happen now. Elvis and Marilyn strode the earth together at the peak of their powers, and I always wondered what would have happened if they were in the same picture together. (Marilyn was 10 years older, but I doubt that would have mattered.) Knowing The Colonel’s management methods, I suppose something like Viva Las Vegas, with Ann-Margret, is likely what we would have seen.

At Manhattan and Meeker Avenues, John Ottati left a legacy in 1900 that he had no way of knowing would be seen by vehicles tooling past on the BQE, opened here in 1939, at 60MPH. To be sure, Ottati had a profit motive when he built this 3- or 6-family walkup here, but he was sufficiently proud of his achievement, and rightly so, to emblazon his name and the date of construction right there on the pediment, a common practice in that era. Subsequent owners, to their credit, have maintained the name and date. I doubt today’s developers are sufficiently proud of their creations to do this, whether the practice comes back into fashion or not. RIGHT: a flag has been hung in the window at 400 Manhattan. It has been hung incorrectly, however; the star field should be pointed toward the north or east.

I used to think Meeker Avenue was built as the service road under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in the 1930s, but I was incorrect about that — it shows up on maps as early as 1855, running from Ewen Street to Newtown Creek. Later maps show an extension west to Union Avenue even before the BQE was constructed.

Walking on Manhattan south of the BQE. Like most of northern Brooklyn, the avenue here is Aluminum Siding City; armies of “tin men” must have spread across the region in mid-century, burying brick sidings and wood frames under the monotonous covering.

There are some mavericks along the way that bucked the trend, such as the brick beauty top left between Withers and Jackson.

The School Settlement Association, founded in 1901, was one of the first settlement houses established in Brooklyn and the only remaining such in the borough. Its handsome brick building at Manhattan Avenue and Jackson Street was constructed in 1914.

Smokestacks are profiled before some new construction between Jackson and Skillman Avenue.

Another yellow brick masterpiece with red accents (but window guards are apparently necessary) between Skillman and Conselyea Street.

At Manhattan and Conselyea, an amazing-looking alternating red and yellow brick-faced residence (the long and short brick technique is known as Flemish bond). Unfortunately the concept was not carried over to the Conselyea Street side, but I’ll take what I can get.

PS 132, NE corner Manhattan and Metropolitan Avenues.

Located in an area where old-time bagel shops are making way for artsy brunch spots, PS 132 in Williamsburg is changing along with its neighborhood. Principal Beth Lubeck-Ceffalia, who took the helm in 2003 after two years as assistant principal, rearranged and redecorated much of the school, inviting local artists in to paint colorful murals. The building’s overall tone is inviting and pleasant. Whereas test prep and old-fashioned reading-lesson books had long defined instruction at PS 132, classrooms now have such hallmarks of progressive-style education as libraries of children’s literature, and lessons focused on group work. Hallways are wall-papered with student work and art projects. The inviting tone extends to the principal, whose office, on the day of one of our visits, displayed a sign-up sheet for children who wanted to come to read to her. Inside Schools

PS 132 also has the kiddies doing yoga. Your webmaster attempting this in grade school, then as now, would make for some comical video. Which will never be shot.

East Williamsburg’s “Little Italy” section is, as we’ll see, clustered along Graham Avenue, but there’s some spillover to Manhattan Avenue; here is the Fortunato Brothers Café and Pasticceria on Manhattan Avenue and Devoe Street. I have always found abandoned storefonts fascinating — both Manhattan and Graham Avenues have a few.

Quite a contrast at Ainslie Street about what’s esthetically proper and pleasing, as an early 2000s glassy-front building (remember your curtains!) is two doors down from a circa 1900 brick building, typical for its genus, with corbelled facade, curved window lintels, and identifying street signs on the side. Of course, this was built when Manhattan Avenue was still Ewen Street.

Prior to about 1890 or so the common practice was to simply ID cross streets via building signs or carvings (as is still done in places like London, UK). Sometimes, street signs would be mounted on gaslights, but the practice gained momentum only after large, wrought or cast iron street lamps began to appear catercorner on just about every corner in the early 1910s.

Thomas Guidice was a detective with the NYPD’s Citywide Auto Squad and president of the Conselyea Street Block Association as well as an active member of a number of other organizations including Community Board 1, Brooklyn. Timesweekly

The city has installed hundreds, if not thousands, of these street signs honoring local residents in recent years, and unless they are labeled “firefighter’ or ‘police officer’ no one except locals, or immediate families, know who they are. Further identification is called for, you would think.

I found another exposed brick building at Powers (I believe it is a women’s center), and its opposite number across the street, gun metal gray again. Perhaps the same builder put all of them up.

Grand Street/Manhattan Avenue. An army-navy wear wholesaler has unsuccessfully camouflaged his roll down gated doors. On the north side of Grand I took notice of a mid-block building (not that rusted balcony special, but the building to its left). Now THOSE are window lintels. I have been shooting many ancient fire alarms in hopes of doing a page soon — some are living fossils that go back to the 1910s.

At #230, just south of Grand, there’s a 4-story walkup from 1900-1910 or so, the match of its neighbors…except that the ground floor was Deco-ized in the 1920s or 1930s, and the renovator’s wife, girlfriend or sister, Joan, has here been immortalized.

Or has she…there’s Joan Rivers, Collins, Baez, d’Arc, Osborne, Armatrading, Crawford, Jett, Didion, Van Ark … or maybe there’s …

Maujer Street forms the northern boundary of the Williamsburg Houses. Despite the Dutch-looking name, attorney Daniel Maujer (1809-1882) was from Guernsey, one of Britain’s Channel Islands. He became an alderman in the 15th Ward, which once encompassed this area. In 1937, 55 years after his death, his name was unearthed and plopped onto the former Remsen Street to avoid confusion with the Brooklyn Heights street so named. How is it pronounced? My guess has always been “Moyer”, but perhaps the locals are more literal-minded and say “Maw-jer.” (cf. Luquer Street). Bottom right: the steeple belongs to the Lutheran Church of St. John the Evangelist (1883); Ten Eyck Walk, bearing perhaps original metal sign lettering, replaces Ten Eyck Street in the Houses. It is pronounced the way it looks, and means The Oak in Dutch.

Williamsburg Houses

From the ForgottenBook: Public housing projects usually disappoint me; they’re usually depressing and dismal, tall buildings without personality plopped into a plain of concrete or nondescript green. Some, like Stuyvesant Town or Parkchester rise above the rest, and then there’s a very special case in Williamsburg: the handsomest housing project in town.

Williamsburg Houses, occupying 12 blocks and approximately 23 acres between Maujer Street on the north, Scholes on the south, Leonard on the west and Bushwick Avenue on the east, were one of the very first housing projects built in NYC, reaching completion in 1938, before the dismaying ‘boxes-in-a-park” pattern took hold. They were built by the Williamsburg Associated Architects, which comprised Shreve, Lamb and Harmon (who designed the Empire State Building) and Swiss architect William Lescaze, in a streamlined “International” style. Facades in tan brick alternate with entrances and storefronts in blue tile, and the buildings, built in a capital “H”, small “h” and capital “T” shapes, are angled at 15 degrees to the street grid. The Williamsburg Houses pioneered the ‘superblock’ concept as Stagg and Ten Eyck Streets were interrupted to vehicular traffic and their roadbeds given over to pedestrian traffic. Never before had streets been closed to accommodate housing.

The contrast is striking at Manhattan Avenue and Scholes Street, where a corbelled brick building is still hanging in there despite cell phone tower excrescences, while a Gun Metal Gray residence rises down the block. Meanwhile, a Ewen Street sign, evincing great care in the design, is still visible at Montrose Avenue.

Turning left on Montrose…

Most Holy Trinity

Like a magnificent Gothic cathedral, Most Holy Trinity/St. Mary’s Church rises on Montrose between Manhattan and Graham Avenues. The parish was founded in 1841, this church was constructed in 1882, and the parish merged with St. Mary’s, a few blocks away at Leonard and Maujer, in 2007. The parish’s lengthy history is linked online. There are many secrets within, including the crypt-like resting place of the parish’s two founders. Don’t miss it!

For more exquisite neo-Gothic greatness there’s the Most Holy Trinity School next door, reconfigured as the Sts. Joseph and Dominic Catholic Academy of Williamsburg in 2005. Note the stained-glass sign over the front entrance and the intricately carved lettering on the cornerstone. The church also provides a detailed webpage on the school’s history.

The parish rectory is a sober, red-bricked, 5-story expanse on Graham and Montrose Avenues. I have always loved solid brick construction like this — as I type this, I am sitting in a two-story brick building that is insulating me from cold winds very effectively.

That concludes the Manhattan-Montrose leg of the trip but fear not …