In September 2008 I took a ride up north … about as far north as you can go in Manhattan and still be on Manhattan Island. Because every rule has an exception, there is a piece of Manhattan actually on the mainland, Marble Hill (although it technically had beenon the island, then was an island on its own, then was grafted onto the mainland). I’ve visited Inwood before, and surveyed Inwood Hill Park (it contains the remnants of Manhattan’s last primeval forest and caves where the native Lenape used to shelter), and ForgottenTour #7 rolled through way back in October 2000.

Checking the Manhattan map, I noted, as many must have done before me, that of the five major Manhattan place names that begin with the letter I, only Irving Place is downtown. The remainder are all in Inwood! That alone is enough to make me consider a neighborhood for exploration. I also noticed a mess of little one-block streets I had not yet visited. And so it was off on the #1 train to visit Manhattan Island’s northernmost province.

Inwood is located in a fairly well-defined area: Manhattan is so narrow at its northern end that you can say that anything north of Dyckman Street is in Inwood. On a map, that works out just fine. By walking around, though, you can detect three separate sub-neighborhoods: anything east of the el on 10th Avenue is gas stations, auto repairs, and supermarket wholesalers; between 10th and Broadway are apartment houses, mom and pop shops, and bodegas; and west of Broadway is the most unusual Inwood of all, since mixed in with the apartments (some of them in gorgeous Deco) you find standalone single and two-family homes, a true rarity in Manhattan, as well as the vast, wild Inwood Hill Park. This day I chose not to ramble in the park (you can find park pictures on my above links) but chose to wander into those spots in Inwood I’d missed before. There are several aged items (besides your webmaster) kicking around up here.

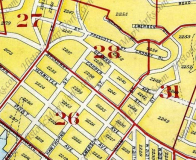

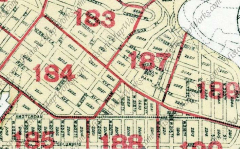

Inwood maps, 1914 (left) and 1930. At the top of both maps is shown the territory that became today’s Inwood Hill Park: the Lenape called it Shorakapok (Kappock Street, in Riverdale across the Harlem River, is a shortened form of this). Though it’s often mistakenly surmised that Peter Minuit made his famed purchase of Manhattan Island from the Native Americans at the Battery, the deal was most likely done in what’s now Inwood Hill Park in 1626. During the Revolutionary War, colonials erected Fort Cox, or Fort Cocks, overlooking the Hudson River.

After independence was attained, for the next century and a half, Inwood Hill Park was occupied by a variety of country homes (Isidor Straus and his wife Ida, who lost their lives in the Titanic disaster, lived here — two more I’s) and philanthropic institutions. A system of winding roads, seen at the top of each map, traversed the hilly ground. Some of them now describe park paths. The City took title to this territory in 1916 and gradually, for the next 25 years, Inwood Hill Park as we know it was developed. The park includes a salt marsh and ‘virgin’ forest left over from the pre-colonial period.

Note Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues at the bottom of the 1930 map. For a time the city tried to apply these uptown monikers to the pieces of 9th and 10th Avenues found here, but they didn’t catch on. By 1930, Hawthorne Street had been renamed West 204th, Emerson West 207th,while Academy and Isham kept their names.

GOOGLE MAP: PRESENT-DAY INWOOD

Both of NYC’s 10th Avenues, in Manhattan and in Brooklyn, have a short stretch of elevated train running over them. In Manhattan it’s in Inwood from West 206th Street and Nagle Avenue north to Broadway and West 215th. Here, the el is a northern extension of the IRT 7th Avenue line, carrying the #1 local service; this stretch of the el opened in early 1906. You will find some Belgian-blocked stretches here. 10th Avenue recently received a clutch of new, cylinder-shafted stainless steel lampposts. West 207th extends over the Harlem River to the Bronx via the University Heights Bridge.

9th Avenue and West 207th, Lebron (or is it LeBron?) Restaurant Supplies.

Martinson’s Coffee faded ad, West 205th east of 10th Avenue. According to legend, the term ‘cup of Joe’ originally referred to Joe Martinson’s coffee. It’s more plausible that it was arrived at from the earlier term “java.”

258 Nagle Avenue. I have been collecting mermaid images all over town.

Apartment buildings along Sherman Avenue between Academy and Dyckman Streets. The avenue is named for some early 19th Century area inhabitants, as is Sherman’s Creek, an inlet accessible from 10th Avenue and West 201st Street.

165 Sherman Avenue hardware store, or ferreteria, Spanish from the Latin root for iron — also seen in the chemical symbol for iron, Fe, and the adjective ferrous.

Of course, when I see the Spanish word ferreteria, I think of ferrets, and by extrapolation, Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani.

After NYC banned ferrets as pets, an outraged Giuliani, who had a Friday morning radio call-in show on WABC-AM in 1999, laced into a caller, David, of Ferrets Rights Advocacy [sic] who complained about the ban:

There is something really really very sad about you. You need help. You need somebody to help you. This excessive concern with little weasels is a sickness. I’m sorry. That’s my opinion, you don’t have to accept it. There are probably very few people that would be as honest with you about that. But you should go consult a psychologist or a psychiatrist and have him help you with this excessive concern – how you are devoting your life to weasels.

It’s a strange world ….

“Ehrmann,” Vermilyea Avenue east of Dyckman. Max Ehrmann is the author of Desiderata, one of my favorites, but this was a TV repair shop owned by Theodore Ehrmann. The remainder of this painted wall ad has been rendered completely illegible.

A number of streets in NYC with Dutch, or Low Country, roots end in -yea or -you, such as Cortelyou, Duryea and Vermilyea. The spellings are English transliterations; the original Vermilyea was Isaac Vermeille, a Walloon (a province in Belgium) who settled in the area in 1663.

I went placidly amid the noise and the haste, continuing along Dyckman and finding this “storefront” subway entrance to the 8th Avenue IND (A) line just west of Broadway. This station opened in September 1932. Manhattan’s hilly topography in Inwood and Fort Tryon, just to the south, made engineers design unusually-proportioned subway stations iwth nonstandard entrances.

I always thought it odd that the IND stops short at West 207th without proceeding any further north — western Riverdale remains subway-free, but the denizens of that ritzy area likely would now object to any subway being built there. The Dyckman Street station does have a non-revenue underground connection to the 207th Street Subway Yards east of 10th Avenue and north of West 207th.

I wanted to investigate a number of small streets I had seen on maps for years but had never viewed in person. Henshaw and Staff Streets are two such streets — in another section of the 1914 map shown above, the two one-block streets, running between Dyckman Street and Riverside Drive, are part of a number of streets labeled alphabetically. Henshaw and Staff are B and C Streets, respectively. The two streets were given names in 1921, with Henshaw honoring a young man from the neighborhood, John G. Henshaw, who contracted influenza and died during his World War I service.

Staff Street is the more picturesque of the two, since its western side borders an Inwood Hill Park extension, and residents of the upper floors of the apartment building near Riverside Drive must have a choice park view, as well as the Hudson River and Palisades beyond. Staff Street is named for Sergeant Harry Staff, who lived on Sherman Avenue, killed while in World War I service. Henshaw and Staff references: Naming New York by Sanna Feirstein

I found a pair of decades old painted signs on the building on the SE corner, Dyckman Car Wash and Magic Novelty, both still in business. Magic Novelty, here on Dyckman Street since 1940, does not produce magicians’ props, as I had thought, but costume jewelry.

Note that both Henshaw and Staff Streets are paved with concrete plates, instead of the usual asphalt.

The northbound Henry Hudson Parkway makes a dramatic appearance over Dyckman Street on a steel and concrete arch bridge. The southbound road is carried on a rather more staid span, while Amtrak, formerly NY Central, brings up the rear. The parkway connects West 72nd Street with the Saw Mill River Parkway and Mosholu Parkway in Van Cortlandt Park and was completed in 1937. As a parkway, it admits non-commercial traffic only.

N.Y.C. R.R. substation No. 10, Dyckman Street and Henry Hudson Parkway.

Chalet-style Inwood Hill Park house (built 1939), Dyckman Street and Payson Avenue

According to a study of the Harlem River done by Columbia University’s Department of Historic Preservation, “the New York Central Railroad Substation was built in 1930 to provide electrical service for the trains on the NYCRR’s Hudson River line. The five-thousand-square-foot, two-room, brick structure is an example of the pre-Columbian style of Art Deco… employing motifs borrowed from Aztec and Mayan cultures…” via Nathan Kensinger: see his photos from within

Tubby Hook

An old name, recently revived somewhat, for Inwood between Broadway and the Hudson River along Dyckman Street is Tubby Hook, possibly named for a 16th-Century Dyckman in-law Peter Ubrecht; time has a way of contracting and corrupting names. Here is a view across the Hudson River to the palisades in Englewood, NJ. A ferry across the hudson launched from the west end of Dyckman Street and ran to Englewood from 1915-1942, closing when the George Washington Bridge proved too tough as a competitor.

Another view of the Hudson, this time looking north. The Tappan Zee Bridge can be seen at the horizon on this crystal clear afternoon.

Payson Avenue is a narrow lane bordering the east side of Inwood Hill Park from Dyckman Street to Seaman Avenue. Formerly called Prescott Street, it was renamed in 1921 for George Shipman Payson (1845-1923) the pastor of the nearby Mount Washington Presbyterian Church from 1880-1920. Attached 2-family houses, unusual in Manhattan, can be seen here.

When looking at Payson Avenue on a map I had always wondered if it were somehow connected with Joan Whitney Payson (1903-1975), owner of the Mets for the first decade of their existence (with husband Charles Shipman Payson, along with George Herbert Walker Jr, an uncle of President George Walker Bush). I still can’t ascertain a direct link, but her husband Charles Shipman Payson and George Shipman Payson, for whom Payson Avenue was named, must be linked by family somehow.

ForgottenFan T.J. Connick sent a detailed genealogy. The Reader’s Digest condensed version:

Rev. George Shipman Payson (1845-1923) and Charles Shipman Payson (1898-1985) share common paternal bloodlines, both being direct descendants of Rev. Seth Payson (1758-1820). Rev. Seth Payson, an associate while at Harvard of Rufus King (you know him), married Grata Payson (part of the same clan). Seth Payson, the son of a famous minister, Rev. Phillips Payson (1704-1778), was father and grandfather to several ministers, foremost among them his son Edward Payson (1783-1827). Another son of Seth Payson, Rev. Phillips Payson (1795-1856) served as the first minister of Leominster, MA.

Our subjects descend from Rev. Seth Payson through his ordained sons. Charles Shipman Payson was great-grandson of Rev. Edward Payson, and George Shipman Payson was the son of Rev. Phillips Payson.

For more on the Whitneys, look no further than the New York Social Diary.

Beak Street runs between Payson and Seaman Avenues for one block north of Dyckman. None of my sources can account for the origin of the name, but one guess is perhaps London’sBeak Street in Soho — perhaps a Londoner developed the area.

I gather from a 1985 NY Times article that Beak Street and Payson Avenue used to be Belgian-blocked, but the city removed them and repaved the streets that year — the City was more expedient about such things then — the stones might well have been preserved in 2010.

94 Payson Avenue, a Deco apartment building, fronts on Beak — perhaps the Payson name was considered a more prestigious-sounding name.

Cumming Street is yet another one block street, running between Seaman Avenue and Broadway. As with Beak Street, it was named in 1925, but the Board of Aldermen (the precursor to the City Council) did not give an attribution, according to Feirstein. I was attracted to the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church signboard.

I could mention strange NYC intersections like Gold and Water, Crystal and Waters, Randolph and Scott, President and Clinton, Bush and Clinton, and Miles and Davis, but I refuse comment on Seaman and Cumming.

A massive, huge apartment building with stores on the ground floor at Broadway between Academy Street and West 204th Street. The brick building was likely constructed in the 1920s and the exterior, at least, is stylish and executed with panache, with arched windows on the top floor. Academy Street was named for the predecessor to PS 52, a large Tudor building torn down in 1957.

Dyckman Farmhouse

The historical centerpiece of Inwood is the Dyckman Farmhouse at Broadway and West 204th Street, which has been here since about 1785 and is Manhattan’s last remaining Colonial farmhouse. It was built by William Dyckman, grandson of Jan Dyckman, who first arrived in the area from Holland in the 1600s. During the Revolutionary War the British took over the original Jan Dyckman farmhouse; when they withdrew at the war’s end in 1783 they burned it down, perhaps out of spite.

The farmhouse was rebuilt the next year, and the front and back porches were added about 1825; the Dyckman family sold the house in the 1870s and it served a number of purposes, among them roadside lodging. The house was again threatened with demolition in 1915, but it was purchased by Dyckman descendants and appointed with period objects and heirlooms. It is currently run by New York City Parks Department and the Historic House Trust as a museum. A copy of one of the occupying British soldiers’ log huts, with a log roof, can be found at the back of the house. The cellar kitchen is particularly engaging, with old waffle irons, sausage stuffers and a child’s game board.

The Dyckman place is, indeed, a respite from the “noise and haste” I referred to earlier. Visitors are welcome: call 212 (304-9422) or visit dyckmanfarmhouse.org for details.

The straight lines and seamless quality of Art Deco: Cooper Street and West 204th, left; Seaman Avenue between West 204th and West 207th. While Cooper Square downtown is named for inventor and philanthropist Peter Cooper, the uptown Cooper Street honors author James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) best known, perhaps, for The Last of The Mohicans.

West 207th between Seaman and Broadway: To allow residents access to this apartment complex built on a hill, an elaborate stone staircase has been constructed, comlete with bum spikes to discourage loitering.

A fortuitous occurrence, as the girl in the hot pants was passing under the painted Frank’s Shoe Repairs sign just when I noticed it.

One of two of New York City’s last public gaslamps can be found where Broadway, West 211th and Isham Streets make a triangle. (The other public gaslight is at the end of Patchin Place, an alley off West 10th Street in Greenwich Village; it has been electrified). Though I have evidence from lamppost king Bob Mulero that a number of former gaslight sidewalk fixtures made it all the way into the 1970s and perhaps the early 1980s, this particular one has now seen a full century on Broadway and parts of two others.

Electric-powered streetlamps began ousting the short gas lamps around 1900. Indeed an original version of the Corvington longarmed post, seen in the background at left, lit wide boulevards, replacing the older gaslamps. I’d like to see if the Landmarks Preservation Commission would consider this post, though that would be a tough prospect in that the lamp has lost its wick.

Isham Street marks yet another “I” in this part of town. A local estate was owned by William Isham beginning in the 1860s, and his daughter donated land that became Isham Park, which borders on yet another “I” throughfare …

Indian Road

This short Road, the only public thoroughfare called “Road” on Manhattan Island, runs along the east end of Isham Park (which is actually contiguous with Inwood Hill Park) from West 214th north to West 218th Streets. It is actually a remnant of Isham Street, which once curved north along the edge of estates that once occupied Inwood Hill Park’s territory. I had wondered why the name of this road hasn’t been changed as it is outdated, but a wikipedia entry proves that to be incorrect:

A 1995 US Census Bureau survey found that more Native Americans in the United States preferred “American Indian” to “Native American.” Nonetheless, most American Indians are comfortable with Indian, American Indian, and Native American, and the terms are often used interchangeably. The traditional term is reflected in the name chosen for the National Museum of the American Indian, which opened in 2004 on the Mall in Washington, D.C.

Indian Road was given its name in the early to mid 1910s after Native American artifacts were discovered in land that became part of Isham Park. Indian Gardens can be found on West 215th just east of Indian Road.

On such a gorgeous day I did venture briefly into Inwood Hill Park (strictly speaking, passing through Isham Park to get there) and snapped the Henry Hudson Parkway spanning the Harlem River on another arch bridge with the same name as the parkway. The double decked bridge was completed, along with the rest of the parkway, in 1938, with the top deck opening two years earlier. In 2010 it cost $3.00 to cross the bridge in each direction.

The blue and white Columbia University “C” has been painted and repainted on the gneiss rock facing the Harlem River since 1952. It is 60′ x 60′. Columbia swim teams have raced from the Manhattan to the Bronx sides at the C across the river for decades. Wien Stadium, used by Columbia for football, soccer and other sports, is nearby on Broadway.

I could not venture into Inwood without paying homage to the Seaman Estate Arch at Broadway near West 215th Street. From the ForgottenBook:

This is the last remnant of the Seaman estate: John and Valentine Seaman obtained 25 acres of land from Broadway to Spuyten Duyvil Creek and what would be West 214th-West 218th Streets in 1851 and set about building a hilltop mansion. The arch, meant as a gateway to the estate, was first built in 1855. Marble from quarries in the area was used in its construction. Evidence of a large gate, and even a room for a gatekeeper, are still in evidence at the back of the arch.

Between 1905 and 1938, the estate passed to Lawrence Drake, a Seaman nephew, and then to contractor Thomas Dwyer, who built several brick buildings on the site and razed the hilltop estate. Since then, it has served as a relic of the Seaman’s once grand domain; sadly, it has been left to deteriorate, although in 2010 it seemed to have attained stability at last.

Time to go back to Queens; I entered the Broadway el at West 215th. All the stations on the elevated employ a Swiss chalet motif, with intricate ironwork on the staircase roofs and railings that would never be attempted today.

erpietri@earthlink.net

Photographed September 2008; page completed January 31, 2010

©2010 FNY