BY SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY contributor

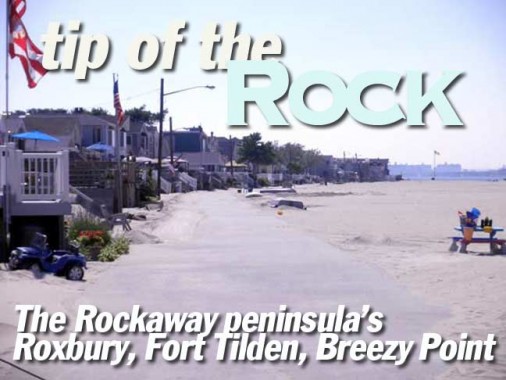

The Rockaway Peninsula of Queens never disappoints an urban explorer. Physically separated from the rest of New York City by water, it often feels like a forgotten sixth borough. The borough’s southwestern tip, Breezy Point is a collection of gated communities, military history, and unspoiled nature. Without a special parking pass, my only options here are either walking or biking. After parking my car in Roxbury, I explored this quiet cape.

Roxbury

Roxbury is bound on three sides by public parkland, and the Rockaway Inlet to its north. It is one of the three communities affiliated with the Breezy Point Cooperative, which runs the gated communities of the peninsula’s tip. The public parkland is the Gateway National Recreation Area, and any private lands inside the park are designated as inholdings. This includes Roxbury, Rockaway Point and Breezy Point.

The neighborhood was founded in the early 20th century by Irish immigrants as a bungalow colony on a peninsula full of bungalows. While most bungalow colonies were replaced with housing projects and empty lots, the huts of Roxbury became year-round, kept their Irishness, and continue to prosper in their isolation.

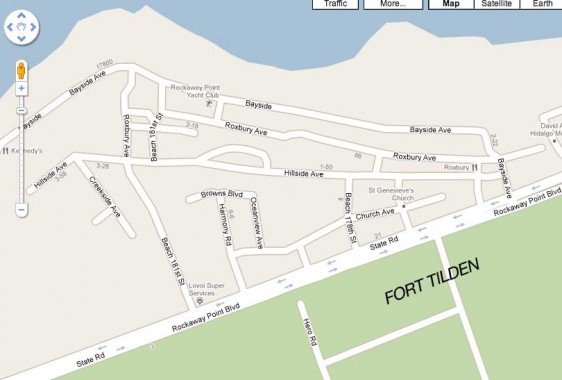

Since Roxbury is a private community, many official NYC street maps present an inaccurate rendering of the street layout, but Google comes as close to reality as possible. The community is located along Rockaway Point Boulevard (State Road) north of Fort Tilden west of the Marine Parkway (Gil Hodges) Bridge.

Sand is everywhere. While the demographics describe Roxbury as one of the city’s whitest neighborhoods, there is plenty of individuality expressed on the homes, with diverse decorating tastes. But we’ll talk more about race later.

New York is often criticized by some middle Americans as a secular, liberal hotspot. But in Roxbury is different. Its devotion to religion and patriotism give the impression of a Norman Rockwell painting. Local vehicles wear their beliefs on their fenders. They also carry special permit stickers to park in the area.

Roxbury has its own regulation street signs, and like its parent city, some of its streets have been honorifically renamed for prominent local heroes. Bayside Avenue (below) fronts an expansive beach on Rockaway Inlet, with views of the Marine Parkway Bridge. In the distance beyond the flagpole are the apartment projects of Coney Island, a world away from Roxbury. Resisting the street numbering grid of the peninsula, only Beach 181 and Beach 184 Street were admitted into Roxbury.

Feimer Promenade (left), Roxbury Avenue

Glazed tiles are a popular method of designating addresses. With very narrow lots, some homes are expanding upward, but how far can they go before regulations step in? State Road is the continuation of Rockaway Beach Boulevard, which is the spine for much of the peninsula.

It’s an endless highway between Beach 184th and 193rd Streets. While most of Fort Tilden has been reclaimed by nature, a small US Army Reserve Center keeps ties to the park’s past. A flag hangs on every lamppost. The first fort on the peninsula was Fort Decatur, a blockhouse built in 1814, to guard against possible British raids. A year later, it was abandoned after the U.S. and Great Britain made peace. It was located near present-day Beach 137th Street, which marked the peninsula’s western tip at the time.

Fort Tilden

The grounds of the former military base have been reclaimed by nature since its decommissioning in 1974. Former streets now ramble through thick shrubbery. From the top of Battery Harris East, the Marine Parkway Bridge dominates the view. Built in 1937, the bridge could be lifted to 150 feet above water, anticipating a major Jamaica Bay seaport that was never built. The bridge’s name anticipated a waterfront parkway that was also never finished.

Resembling an overgrown hilltop, the defunct battery offers sweeping views of the tip. Hardly a building in sight, it’s hard to believe that this scene is within New York City limits.

The underbelly of the fort offers enticing urban exploring opportunities, but my fear of strangers lurking got the best of me, and I decided not to venture further.

The Silver Gull Club is the only address on Beach 193rd Street, an empty boulevard once destined for high rise housing in the 1960s. By 1979, local opposition killed the project, and the concrete building skeletons were demolished. The land on both sides of this street is now part of a larger nature preserve. As for the club, it sits at the end of the street, with its own private oceanfront beach, swimming pool, and cabanas overlooking the shore. Adult membership is $480 per year.

On the Beach

While it is easy to walk the mile from Fort Tilden to the Rockaway Point jetty, signs everywhere remind travelers that is land belongs to a private co-op. The private land is tucked inside the National Park land, grandfathered for private use, because it predates the park.

The tip continues to move westward, shaped by currents. But in the 20th century, the sand was sculpted by jetties, to prevent it from clogging Rockaway Inlet. In 1935, the line was drawn with a half mile-long jetty, preventing the borough of Queens from extending further west. As a result, the sand is now expanding towards the south. Since 1960, more than 100 acres of new land has been naturally added to Breezy Point, and there was a court case to decide whether the new land belongs to the private community or the federal government. In 1982, a federal court ruled for the Breezy Point Cooperative.

This Google aerial view shows undeveloped dunes on the southern edge of the cooperative. Those formed after 1960, and a decision was made not to build on them. The outline of the older shoreline forms the southern edge of the Rockaway Point neighborhood.

On the western edge is the square grid of the Breezy Point community. The large parking lot beyond Beach 222nd Street belongs to the Breezy Point Surf Club. Its address is 1 Beach 227th Street, the last street number on the peninsular grid. Membership for a single adult costs $910. A guest must be invited by a member and fork over $50 for a day’s use of the facilities. The rates seem more Hamptons than Rockaway.

On the eastern edge is the nature preserve that was once slated for high rise housing.

Where Queens Ends

A humble beacon marks the tip of Rockaway peninsula. In contrast to some of the city’s other major capes, there is no dramatic lighthouse to mark this spot. The city has a few of them, including Norton’s Point in Brooklyn, Jeffries Hook in Manhattan, Roosevelt Island, and one that defines a book publisher in the Bronx.

The mighty Ambrose Channel separates Rockaway Point from the highlands of New Jersey. Before the last Ice Age, the Hudson River carved a canyon into the continental shelf, but as the sea level rose, the valley was flooded, creating the channel and Lower New York Bay. In 1902, Congress named this channel after John Wolfe Ambrose (1838-1899), a proponent of dredging the channel. A 19th century master builder, Ambrose built the 6th Avenue El, pneumatic tubes for Western Union, streets in Harlem, and docks in Brooklyn.

The jetty (below) separates the beach from the Lower New York Bay. Across the channel, the New Jersey highlands end at Sandy Hook. On the left, the breakers are made for surfing, but on the right are the calmer waters of the bay. At the tip, the sand deposits shells, arrowheads, and debris that floated westward with the current, captured by the jetty.

Everything appears cramped together, with all of Coney Island framed by the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. The hills of Staten Island appear on the left. The waters are calm because between Rockaway Point and Coney Island lies the East Bank, a shoal with a minimum depth of only 4 feet below the surface. The waves in the middle of the picture are crashing above the shoal, which is surrounded by dredged channels.

Breezy Point has a fire control tower from the Second World War, designed to keep Nazi submarines out of Jamaica Bay. It has since gained a new life as a symbol of the Breezy Point Cooperative.

Besides its privacy, the neighborhood is also known as the city’s whitest enclave, with some 98 percent of its residents descended from European immigrants. In a 1991 protest outside Brooklyn DA Charles Hynes’ summer house, Rev. Al Sharpton described Breezy Point as an “apartheid village.” Residents argue that the reason for the whiteness isn’t racism as much as a low vacancy rate, which gives the few available homes to friends and relatives of existing longtime residents. Like any Manhattan co-op, applicants for Breezy Point must be recommended by existing members, meet certain income guidelines, have a clean crime record, and receive final approval by the co-op’s Board of Directors.

While the memorial in downtown Manhattan slowly inches towards completion, other city communities have designed their own tributes to the local residents who perished. Because Breezy Point had a sizable contingent of police officers and firefighters, it felt a disproportionate impact from the attack. Like the Staten Island 9/11 memorial, this one also faces towards the site of the World Trade Center, atop a dune, with corners for private reflection and personalized memorials to the 24 local residents killed on that day.

Some of the names have Celtic crosses, testifying to the area’s deep Irish identity. Breezy Point even has its own Pipes & Drums ensemble.

As with the Roxbury street map, the Breezy Point street layout has been somewhat couched in mystery for outsiders, given its private nature, and retail street maps have this given only a general idea. Using satellite info, Google has approached near total accuracy.

The only road open to outsiders is Rockaway Point Boulevard. All other streets have electronic gates to keep strangers away. Sand is everywhere, and only a few hardy trees can make it here. For a city as large and populated as New York, there are relatively few gated neighborhoods to be found. It feels egalitarian for anyone to have the same opportunity to park on Manhattan’s Park Avenue. The city also has a few private neighborhoods that are not gated, such as Fieldston and Forest Hills Gardens, where outsiders can drive, but not park. Parking on Breezy Point Boulevard is restricted to invited guests and residents.

The King of All Buildings is never out of view, seen from the parking lot of the venerable Kennedy’s Restaurant, which has been feeding local residents since 1910. It was originally a casino. Like Roxbury, “Breezy” and “The Point” also have beaches on the bay. The postcard below is from the restaurant’s website, showing its early incarnation, which included a ferry dock.

Roxbury and Rockaway Point have their own volunteer fire companies, security force, ambulances, bus system, water distribution, garbage collection, parks, and road maintenance. All the trappings of an independent village inside the city, paid by the dues of its residents. City buses do not serve The Point, and a subsidized ferry service was cancelled on July 2, 2010 after only 2 difficult years. Its private bus system costs $1.

The Origin of Breezy Point

The gated co-op was born in a revolt in 1960, when the Atlantic Improvement Company purchased the peninsula’s tip, threatening to replace bungalows with high-rise projects. A mix of political clout, relentless protests, and lawsuits forced the city to compensate the building company, and the remaining undeveloped land was incorporated into Gateway National Recreation Area in 1974. At the time, President Richard Nixon was reaching out to cities with urban national parks. The Golden Gate National Recreation Area was created that same year in San Francisco. But the skeletons of the projects was already complete, standing forlorn until they were taken down in 1979. Over the years, the co-op continued to fight in court to keep its land off-limits to outsiders, even as it is tucked inside a national park, inside the country’s most populated city.

The administrative center of the three-community co-op is a strip mall with offices above its stores. Across the street, there is a small community garden reminiscent of a village square. Even here, parking is restricted only to residents and guests.

Like Roxbury and Breezy Point, Rockaway Point also features the co-op’s signature entrance sign with a heavy accompaniment of patriotism.

As long as its vacancy rates remain low, guest fees remain high, and threatening “private property” signs remain up, few New Yorkers will dare trespass into this unspoiled tip of Queens, and that’s just how the residents would like it.

The entrance carries on the mix of patriotism and privacy. A blessing stands alongside a warning to potential trespassers.

Like Roxbury and Breezy Point, Rockaway Point also features the co-op’s signature entrance sign with a heavy accompaniment of patriotism.

As long as its vacancy rates remain low, guest fees remain high, and threatening “private property” signs remain up, few New Yorkers will dare trespass into this unspoiled tip of Queens, and that’s just how the residents would like it.

The entrance carries on the mix of patriotism and privacy. A blessing stands alongside a warning to potential trespassers.

Sources:

“Behind Closed Gates” By Shane Dixon Cavanaugh. The Architect’s Newspaper 3/10/2010

“New Beach Land Poses Issue For a Gated Town in Queens” By Norimitsu Onishi. New York Times 8/25/1997

“Between Ocean and City” By Lawrence Kaplan and Carol P. Kaplan. Columbia University Press 2003

“Old Rockaway, New York, in Early Photographs” By Vincent Seyfried and William Asadorian. Dover Publications. 2000

Page completed December 12, 2010

Forgotten NY contributor Sergey Kadinsky is a freelance writer, teacher, tour guide and photographer. sergey.kadinsky@gmail.com, twitter.com/#!/sergeykadinsky