Forgotten NY has blazed a trail of urban web photography and commentary for over a decade but sometimes I shudder when I think of the opportunities I missed out on. In 1998 Times Square was a wasteland in transition from the sleazy porn era to the shined up, Disneyfied tourist mecca that it became. They were still actually packing a lot of meat in the Meatpacking, and strolling the streets (that featured two restaurants, Hector’s Cafe and Florent) you caught the delicious and intoxicating whiff of raw cow flesh; and Williamsburg was, well, just about the end of Brooklyn, if not the end of the earth, an industrial afterthought with side streets dotted with 3-story walkups filled with Polish and Czech immigrants. The Poles and the Czechs are still around, but they’ve been totally subsumed by the countercultural – into – mainstream circus/theme park that had descended there beginning in about 2000. I was never able to fully capture these neighborhoods in transition before they transited — since I never knew they were about to transit.

I was able to snatch bits and pieces of these areas before the changes came — I snapped a Dumpster full of bones at Washington and Gansevoort Streets (on my lunch hour working at The World’s Biggest Store), I was able to capture the old Cameo Theatre in its final guise as the Playpen Theatre at 8th Avenue and West 44th; and on a cloudy, cold day in 1998, on a sleepy, deserted Bedford Avenue (which is deserted and sleepy no longer) I snagged an ancient Downer’s Pharmacy awning sign at Bedford and North 4th. The drugstore, which still had an old Ex-Lax laxative ad in one of the windows, later became a bookstore and is now a cheese shop. Perhaps in this walk from South Williamsburg to Bedford-Stuyvesant I might have captured another region in transition — that will look utterly different in ten years, and I can post the pictures and say, “I remember it when…”

I rode the M train for the first time since it switched its route from Queens, into Manhattan, and back to Brooklyn and Queens, taking it from Queens Plaza (no M train had ever previously ventured to the Queens Boulevard line; it’s like your webmaster moving to Cheyenne, WY) and getting out at Hewes Street in South Williamsburg. This station, like Marcy Avenue to the west, allows views of the domed Williamsburg(h) Savings Bank and Williamsburg(h) Bridge, the graffiti on the backs of buildings on South 5th, and new stained glass platform art by Mara Held, El in 16 Notes, installed in 2002.

At Broadway and Hewes Street is the eastern extension of Division Avenue, which marks a change in the orientation of cross streets from SW-NE to a more NW to SE direction (all of Williamsburg’s lengthy avenues, Driggs, Bedford, Wythe) change direction at Division Avenue. The intersection of Division Avenue and Broadway makes for an unusual building plot, with an odd-shaped building that inexplicably hangs a bicycle over the sidewalk; perhaps there was once a bike repair shop here. Strictly speaking, Division Avenue marked the line between the village, later city of Williamsburg to the north and Brooklyn to the south. Williamsburg was annexed by Brooklyn in 1855 and gradually, that wedge of streets bordered by Broadway, Kent Avenue (along Wallabout Bay) and Flushing Avenue (formerly the Brooklyn-Newtown Turnpike) became to be thought of as part of Williamsburg; I tend to call it South Williamsburg.

Today those streets are mostly occupied by Latinos and Orthodox and Hasidic Jews — this makes quite a contrast with the north part of Williamsburg, which has become a new NYC entertainment district in the past decade.

Most signers of the Declaration of Independence have Brooklyn streets named for them, many in South Williamsburg, but others elsewhere in the borough. Stone Avenue (named for Thomas Stone of Maryland) was renamed Mother Gaston Boulevard after Brownsville community activist Rosetta Gaston after here 1981 death, while Paca Avenue (William Paca, Maryland) became Rockaway Avenue and Witherspoon Street (John Witherspoon, New Jersey) became Vernon Avenue.

One of the signers missing in the series, Button Gwinnett (1735-1777) the representative from Georgia. His signature is so rare that it is among the most valuable to collectors in the world; his namesake street here, Gwinnett Street, was renamed Lorimer Street by 1900. Gwinnett perished when he was shot in a duel.

A spectacular painted ad on Hewes Street between Broadway and Harrison Avenue has survived virtually intact from when I first spotted it in 1998, and it had been there for a number of decades before that; it is for “Middlebrooke Lancaster, Inc., manufacturers of Nutrine Beauty Preparations”; this building was likely where it was manufactured. The Nutrine brand is still around — I’m not sure it still operates out of this building. It doesn’t appear that way.

Franklin Cleaners, Broadway and Hooper Street. I liked the simplicity of the black and white signs on both sides of the building.

Name that language, found on a pole at Hewes Street and Harrison Avenue. I’ve found script like this before in the area, but I’m not sure if I got a response the last time I asked about it.

ForgottenFan Larry Berkman: Yiddish

ForgottenFan Stephanie Leveene: First line (reading right to left): getrofn a [last word covered by tape]. In German, “getroffen” is the past tense of “treffen”, to meet. I’m guessing it has the same meaning in Yiddish.

Second line: t’fillin, bitte rofn. T’fillin are small boxes with leather straps on either side. The boxes contain the passage from Deuteronomy about binding the word of God as a sign upon your eyes, or something like that. Orthodox Jewish men bind the t’fillin to their forehead and left arm during morning prayers, using an elaborate series of winds. “Bitte rofn” means “please call [telephone]”, and I see you’ve blocked out the phone number.

ForgottenFan Alex Heppenheimer: The handwritten sign is indeed in Yiddish, and your correspondents have it more-or-less correct. The first line says “getroffen a set,” which means “found a set,” and the second line is “tefillin, bitte rufn” (tefillin, please call). Basically, then, either someone found a set of tefillin (which Stephanie Leveene described well), and wants to return them; or someone lost them, and put up this sign asking if anyone found them.

At the corner of Harrison Avenue and Hewes Street is a building that stopped construction so long ago that the signboard advertising what it was going to be is now empty. I struck off down Harrison Avenue, named for Benjamin Harrison — not the 19th Century US President, but his great-grandfather, Benjamin Harrison V, a representative from Virginia.

WAYFARING: SOUTH WILLIAMSBURG to BEDFORD-STUYVESANT

On Harrison Avenue between Rutledge and Heyward stands what used to be the forbidding, monumental PS 122, constructed in 1905, now a school. The building could use an exterior cleaning. Unfortunately after scouring the internet for 20 minutes, that’s the sum total I know about this massive building. Education was a more serious business then for parents and students, and architects built serious edifices dedicated to learning. Do we need more “tiger moms” whose relationship with their children is like that of a drill sergeant to a private? Your webmaster has never come close to having kids, but I’m glad I wasn’t a “tiger mom’s” kid.

So what does the script mean? Is it Hebrew or Yiddish?

ForgottenFan Dave Steckler: [Top line] “Tent (of) Hannah” The word “tent” is sometimes used euphemistically in Hebrew in place of “home” or “house.”

[Second line] The first two letters on the right are an acronym for “built in the name (of)”. [Next word], “The [rabbi’s] wife, the righteous woman [the word is spelled with a feminine suffix], Hannah Teitlebaum, [the last two letters on the far left separated by a quote mark are an acronym for “may the righteous be remembered”].

[Third line] “Daughter of the holy Rabbi Yael Ashekanzi, may the righteous be blessed.”

So:

“Built in the name of the rabbi’s wife, the righteous woman, Hannah Teitelbaum, may the righteous be remembered, daughter of the holy Rabbi Yael Ashkenazi, may the righteous be blessed.”

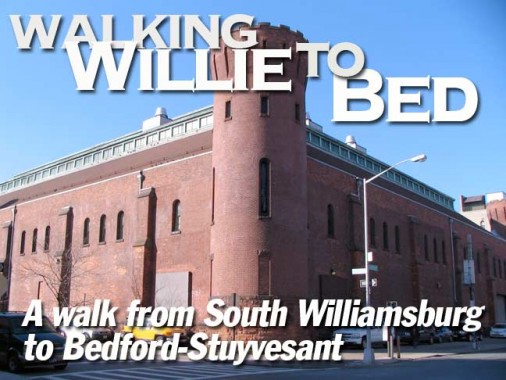

17th Corps Artillery Armory

The 17th Corps Artillery Armory, originally the 47th Regiment Armory, is one of those handful of NYC buildings that fills and entire block, in this case the one border d by Harrison and Marcy Avenues and Lynch and Heyward Streets. It’s so large it encompasses two separate styles, as we’ll see. As it says on the nameplate above the Marcy Avenue entrance, it was constructed in 1883 (William A. Mundell, architect). The 47th was organized during the Civil War and helped suppress the NYC Draft Riots in 1863.

The 47th Regiment Armory was built at a cost of $125,000 and its original building facing Marcy Avenue ws 200 feet by 204 feet, contained eight company rooms and a drill room, and eight rifle galleries in the basement. This was the only state-sponsored armory built in Kings County during the 1880s, with the others being sponsored by the City of Brooklyn or by Kings County.

As the faded signs indicate the building is currently owned and operated by the National Guard.

In 1899 the 47th was almost doubled in size by the addition of a huge drill shed (Isaac Perry, architect) with castle-like towers on the Harrison Avenue side — making this side look nothing like the Marcy Avenue side. info from Nancy L. Todd’s New York’s Historic Armories, SUNY Press, 2006

ForgottenFan Edward Findlay: All of the units listed on the two signs are either disbanded or redesignated or moved elsewhere. It is still being used by the Army National Guard and the soldiers are still doing maintenance work except nowadays it is for the aviation and not ordnance corps.

And something to note about the armory — several blockbuster movies have been filmed there including I Am Legend and Sherlock Holmes…

The Union Grounds

The 47th Regiment Armory is built on one of Brooklyn’s most hallowed sites — if you are a baseball fan. Brooklyn’s first professional baseball teams played here for nearly two decades beginning in 1862, including the team that evolved into the Brooklyn, and today’s Los Angeles Dodgers.

Professionalism was made possible by gate receipts from paid admission into enclosed ballparks, which replaced open ball fields so the teams could keep out non-paying fans. Baseball’s first enclosed ballpark was the Union Grounds in Williamsburg, built in 1862 on the blocks surrounded by Harrison Avenue, Rutledge Street, Lynch Street and Marcy Avenue and featuring a three-story pagoda in center field. It was home of the Eckfords and later the New York Mutuals, who were in reality a Brooklyn team when they went professional and eventually became one of the eight founding clubs of the National League. Jealous of the revenues produced by Union Grounds, the Atlantics built baseball’s second ballpark in Bedford two years later, the Capitoline Skating Lake and Base-Ball Ground (early ballparks were flooded in winter for ice-skating), on the blocks surrounded by Halsey Street, Marcy Avenue, Putnam Avenue and Nostrand Avenue. The Atlantics played at Capitoline Grounds until 1879, including the classic game that ended the [Cincinnati] Red Stockings’ winning streak.

No monument or plaque currently marks either site. Old Brooklyn Baseball

Union Avenue in Brooklyn has had an unusual history: it originally ran from Broadway north to Driggs Avenue, originally 5th Street, with a shorter section from Greenpoint Avenue north to Newtown Creek. By the 1890s, the Greenpoint section had been renamed Manhattan Avenue, but when the IND Crosstown Line was extended south and west in 1937, the tracks ran through the thicket of diagonally-oriented streets in South Williamsburg. When the cut and cover procedure was completed, there was a space devoid of buildings, and Union Avenue was extended south from Broadway to Flushing Avenue to run on top of the subway line.

Attaining Flushing Avenue, you can glimpse the former world headquarters of drug and pharmaceutical company Pfizer, Inc. The company originated on Flushing Avenue in 1849 by Charles Pfizer in a building nearby that still stands. Its first product was santonin, a drug originally used to expel roundworms from the system. It moved its main headquarters to Maiden Lane downtown in 1868; it has frequently moved around since and has branches worldwide.

Its production of citric acid in 1880 became its main business for decades; Pfizer pioneered the production of penicilin in 1941. It would become the world’s #1 maker of the new wonder drug during World War II. After severe cost cutting Pfizer was forced to close its Fluahing Avenue complex in 2007, but pledged to convert its original HQ into the Charles Pfizer Community Education Center, which I’m not sure has yet appeared.

The rather forbidding Woodhull Medical Center at Broadway and Flushing Avenue; it opened in 1982 to replace Greenpoint Hospital.

Tompkins Liquors, Tompkins Avenue just south of Myrtle. FNY has visited Tompkinsville, Staten Island, named for US Representative, NYS Governor and two-term Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins. DDT is all over the NYC map as Tompkins Park in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Tompkins Square Park are also named for him. It is perhaps serendipitous that a liquor store also bears his name, since a charge that he illegally profited from the War of 1812 haunted him for years and led to his downfall by alcoholism.

I’m afraid I know nothing at all about this magnificent towered building at Tompkins and Vernon Avenues. I call it the Vernon Castle, which has nothing to do with the famed British ballroom dancer (1887-1918). Can anyone fill me in?

Another mystery: it’s a near carbon copy of the NYPD 88th Precinct house at Classon and DeKalb Avenues.

The buildings were designed as precincts by the same architect and were built around 1889-90. The current 88th started as Brooklyn’s 4th Precinct and then became the NYPD’s 56th before becoming the 88th in 1929. Old Traffic F (Vernon and Tompkins) started as Brooklyn’s 13th Precinct and then became the NYPD’s 58th before becoming a Traffic precinct in 1922. PoliceNY

I’m fascinated with DeKalb Avenue, from first encountering it in downtown Brooklyn as a kid, riding past it on the way to the now-demised (or Macyized) A & S with the folks in the now-demised B37 bus that used to go down 3rd Avenue. I’d ride it first past the now-demised Albee Theatre at DeKalb and Fulton, and later, I’d ride it past the now-demised Albee Square Mall. Well, the timeless and eternal Dime Savings Bank at Albee Square is still there. DeKalb also rates two seperate BMT subway stops in two separate parts of Brooklyn: downtown and Ridgewood.

On DeKalb off Tompkins in Bedford-Stuyvesant I noticed the Marlborough Apartments, especially the nameplate on the pediment, which is lettered in a curvy sanserif style used in the 1890-1900 period.

I usually don’t like modern vinyl awning signs, but this one, for Pancho’s Foods, boasts terrific block lettering and basic red, yellow and green coloring.

Meet me at Mt. Pisgah

The massive Mount Pisgah Church dominates the west side of Tompkins Avenue between DeKalb Avenue and Kosciuszko Street. The church, and the brick building on the right, were formerly St. Ambrose Catholic Church and School, with the church, awash in terra cotta detail, constructed in 1883, the school 1911. The Catholic church and school closed in 1978, merging with Our Lady of Monserrate on nearby Vernon Avenue. The present occupant, Mount Pisgah Baptist Church, was founded by Rev. Salina Perry in 1931 and the church acquired this building after St. Ambrose moved out. The building’s Catholic legacy, however, can be readily seen in the colorful and ornate terra cotta detailing. In the Book of Deuteronomy, Mount Pisgah was the location where Moses saw the Promised Land after decades of wandering in the wilderness with the Israelites; for previously doubting God, however, he was not allowed to enter it.

1/23/11