BY GARY FONVILLE

Forgotten NY correspondent

It would have been easy to look through a tour book and write a list of common tourist spots in Harlem and then take pictures of them. Some sites here are culled from research and some are from my personal knowledge. Many places will not even be shown by the tour buses that rumble through Harlem. In fact, before Harlem’s gentrification, tour buses from downtown would come up Central Park West, turn east on 110th Street (now Central Park North), turn south on Fifth Avenue and then head back downtown! But don’t even get me started about that. Enjoy the tour!

Rivington Florist at the NE corner of W. 135th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Blvd, must be one of the oldest existing African-American businesses in Harlem. It has been there as long as I can remember, and I’m 59. This sign’s condition caught my eye because the newer one is peeling away, revealing the older non-working neon sign. A bonus here was this baked enamel street sign facing 135th Street. The 7th Avenue (as the street was called when the sign was installed in the late 1800s or early 1900s) is missing.

[Why two fire hydrants? –your webmaster]

I gather, from several emails, that there is more than one main.

55 W. 125th Street looks like a generic office building that would be in midtown Manhattan. It was or is the location of former President Bill Clinton’s New York office. This is an ordinary building except for one feature:

It appears that in order to build a rear garage ramp, a brownstone had to be sacrificed. Folks, this is what can happen when an area or building is not landmarked.

Wood frame houses (which are rare in Harlem) have been previously highlighted in FNY, but not this one on 149th Street, just east of Broadway.

In the days before free agency, baseball players had to supplement their baseball salaries. Can you imagine that in light of the mega millions they make today? Many took off-season jobs or opened businesses. Hall of Famer Roy Campanella (1921-1993) opened Campanella’s Wines & Liquors at the SE corner of 134th Street & ACP Boulevard. He becamse paralyzed in an automobile accident on his way from the store to his home in Glen Cove, NY in early 1958. A bodega occupies this space currently.

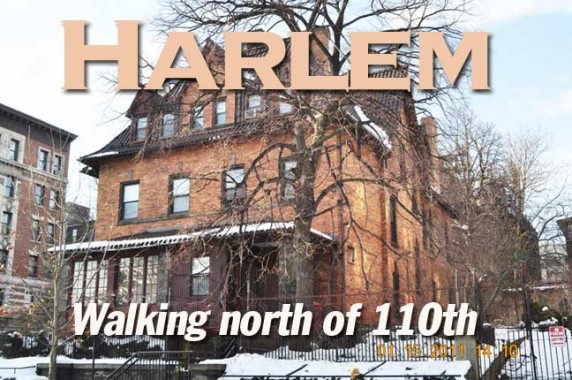

James A. Bailey, whose circus (owned with P.T. Barnum) joined with the Ringling Brothers‘ in 1919, owned this magnificent edifice overlooking Harlem at the northeast corner of St. Nicholas Place and West 150th Street upon its completion in 1888. The house has been owned by Marguerite Blake since 1951. She operated the M. Marshall Blake Funeral Home in the house until a few years ago. Recently the house went on the markey for $8 million. The price was later reduced to $6M, but with plenty of restorative work required.

The house (architect Samuel Burrage Reed) is constructed with walls of grey Indiana limestone. Interior decorations were by a company headed by Joseph Burr Tiffany, the brother of Louis Comfort Tiffany of glassworks fame, and the stained glass windows were fashioned by the Belcher Mosaic Glass Company.

Dawn Hotel, St. Nicholas Place and SE corner of West 150th., constructed in 1886 for provisions merchant architect John W. Fink. It is in relatively rundown condition compared to the Bailey House even as the latter undergoes renovations. Fink sold to entrepreneur Charles Runk and by 1895, it was joined with the house immediately to its south and served as a sanitarium for a number of years. As the Dawn Hotel it has served homeless families as emergency housing.

Brick addition on the West 150th Street side

14 St. Nicholas Place features an ogee (curved and coming to a point) tower. It is just north of the Bailey House.

The Harlem YMCA on West 135th Street between Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevards has been here since the early 1930s. It contained a theater where many famed African-American actors got their start: James Earl Jones, Sidney Poitier, Isabel Sanford (of “The Jeffersons”), Esther Rolle (“Good Times”), Eartha Kitt, Roscoe Lee Browne, and Danny Glover began their theatrical journeys here. Malcolm X rented a room here when he was a young man.

If you’re wondering why the top part of this building is different architecturlely, here’s why. The original building was only three stories. The top part was added about ten years ago. The building now houses the Thurgood Marshall Academy and an IHOP (International House of Pancakes). Earlier the building housed Small’s Paradise, a nightclub which was owned by basketball great Wilt Chamberlain at one time†on the ground floor. Offices occuped the second and third floors. When my aunt worked for an African-American postal workers union on the second floor, during the early 1960s, I remember getting a glimpse of Chamberlain on the sidewalk from her office’s window.

This 1960s façade hides the fact that it was formerly the Lincoln Theater on 135th Street between 5th Avenue & Malcolm X Blvd. It was the first theater in Harlem to cater primarily to African-Americans. Early entertainers who performed here include Thomas “Fats” Waller, Ethel Waters and Bessie Smith.

The Lincoln served as a cinema in the 1940s and 50s, but may have had a larger seating capacity when originally presenting vaudeville and plays. The 850 comes from Film Daily Year Books. According to a recent article in the weekly New York Press, the Lincoln first opened in 1915 and was the first theatre in Harlem (then a predominantly white neighborhood) to cater exclusively to a black clientele.

The Lincoln had its own stock company of black actors, but earned its greatest fame in the 1920s, when it presented black vaudeville, including such headliners as Bessie Smith, Florence Mills, and Ethel Waters. For a time, the very young Fats Waller was its resident organist.

Since the 1960s, the Lincoln has been home for the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. Although there have been decorative changes, “much of the structure remains intact, notwithstanding the tiled, 60s-era facade and dropped ceilings”, David Freeland reports in the NYP story. “A sturdy rectangular proscenium, richly brocaded in lovely floral patterns, dominates the front interior, while the original sloping floor is steep enough to make first-timers wobble. Best of all, the theater’s boxes were never removed, and their gentle, curving lines add delicacy to a space that appears larger than it really is”. Cinematreasures

Much in the same vein as the Metropolitan is the Greater Refuge Temple at A.C. Powell Boulevard and West 124th. It looks considerably different from its early incarnation, 1890, as the Harlem Casino. It became a Loew’s theater by the 1920s and was renovated in 1966 when the church purchased the building. Photo: Harlem Bespoke

Graham Court, at the NE corner of 116th Street & A.C. Powell Blvd was constructed in 1901, originally owned by William Waldorf Astor. As one of Harlem’s largest apartment buildings at the time, African-Americans were not permitted to rent apartments until 1933. It was designed by the architectural firm of Clinton & Russell. The eight-story edifice contains 93 apartments with 8 elevators, and originally an underground stable.

Graham Court … was distinguished not only by its Venetian arched entrance but also by the commodious open courtyard beyond. Landscaped with walks and a driveway surrounding a fountain, the court was a superb means to introduce cross ventilation and additional light and air into the generously sized apartments. Michael Henry Adams, Harlem Lost and Found

It’s easy to dismiss this building as a regular garage if you’re not observant on 150th Street between Amsterdam & Convent Avenues. The two horse heads give a clue to the building’s former use as a stable.

Directly across the street from the garage are these unusual houses, especially for Harlem.

The Harlem River Houses, the city’s first federally funded housing development was constructed in 1937. This development was constructed primarily for African-Americans, while the Williamsburg Houses in Brooklyn were designed primarily for Whites. The development is bordered by 153rd Street, 150th Street, Macombs Place and A. C. Powell Jr. Blvd.

Matthew Henson, the explorer, Paul Robeson, singer/activist, A. Phillip Randolph, civil rights leader, and dancer/entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson called the Dunbar Apartments (bordered by Frederick Douglass Boulevard, A.C. Powell Jr. Blvd., and West 149th and West 150th Streets) home. The development was funded by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. as middle class housing.

I.S. 201, the Arthur A. Schomburg School, at Madison Avenue & East 128th Street may be NYC’s only windowless school. What were the architects thinking?

This school has the title of being the closest to a subway station – it’s built right on top of the IRT’s Lenox Yard at 147th Street & ACP Boulevard.

This brick building on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Blvd, was a major mecca of Harlem nightlife in the 1930s in its incarnation as the Renaissance Ballroom. The “Renny” offered dancing, cabaret acts and the finest bands of the era, including those of Vernon Andrade, Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb. Its builders were William Roach and James Sweeney, from Antigua and Montserrat in the Caribbean Sea.

The adjoining Renaissance Casino was the home court of the 1920s Harlem Rennies, the first all-black professional basketball team, which racked up a 2588-592 record against other local competition in the pre-NBA era.

Left: original home of the Schomburg Library, West 135th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard. Named for the Puerto Rican historian Arturo Alfonso Schomberg, who was the original curator from 1932-1938. It was a repository for African-American culture. A larger, more modern building was built to house its collection in 1978 at 515 Malcolm X Blvd. Right: This wonderfully designed Countee Cullen branch of the NY Public Library sits here on 136th Street, just west of Malcolm X Boulevard. While constructed in 1942, it still looks modern. This branch sits on the site of the home of Madam C.J. Walker (1867-1919), the first self-made female millionaire in the U.S. She later purchased a home in Irvington, NY, where her White neighbors were not too happy about her moving in.

The north side of West 135th Street between ACP & Malcolm X Blvds., was considered the first area in Harlem where African-Americans could live.

This picturesque freestanding house is tucked in the rear of the Bailey House (see above) on Edgecombe Avenue and West 150th Street.

This stretch of Edgecombe Avenue is in the heart of Sugar Hill, a region of relative affluence in Harlem home in the early 20th Century to W. E. B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and Duke Ellington. In the 1980s one of the original rap groups, the Sugarhill Gang, were from here.

A closer examination of the building’s 150th Street side reveals a baked enamel corner street sign. Right: This nearby alphanumeric telephone sign is a relic. The FA stood for FAirbanks.

The Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Harlem Office Building, as it’s called now, sits on the NE corner of 125th Street & A.C. Powell, Jr. Boulevard. This 19 story building was constructed in 1972. There was much friction during its construction over the racial makeup of the construction crews. It was originally called the Harlem State Office Building. The name was changed to honor Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., who served from 1945 to 1970 (his successor was Charles Rangel — the seat has been held by two men for over 65 years). The building was designed by the architectural firm of Ifill, Johnson & Hanchard, an African-American owned firm. Right: “Higher Ground,” a 21-ft. high monument that includes a 12-foot high rendering of Powell, was sculpted by Branley Cadet and was dedicated February 17, 2005.

The former dry goods/department store H.C. F. Koch and Company Building was constructed on 132 West 125th Street (Martin Luther King Blvd.) between Malcolm X and A.C. Powell Boulevards in the 1890s. It was originally in Ladies’ Mile at 6th Avenue and West 20th Street but moved uptown.

The 369th Regiment Armory is located at 5th Avenue and 142nd Street, about as far north on 5th Avenue you can go before it meets the Harlem River. The 369th (the “Harlem Hellfighters”) Infantry Regiment was the first African-American regiment to fight in World War I. Due to the segregationist policy in the US Army it was under French command.

The armory was constructed in 1933 and bears the Art Deco touches so prevalent in that era.

Possibly Harlem’s oldest faded ad on West 128th between Douglass Boulevard (8th Avenue) and St. Nicholas Avenue, this harks back ton a much more rural period, likely the 1870s or 1880s. (Until recently an R. H. Macy ad advertising uptown stables coule be seen on West 147th).

One of the many Charles H. Fletcher Castoria ads still visible around town on the south side of West 133rd between Douglass Boulevard and St. Nicholas. It was positioned to be seen from the now-demolished 9th Avenue El.

2/13/11