I was heading to a birthday thing the other Saturday and found myself along Kings Highway, Brooklyn’s Mother Road, a colonial-era route built partially atop a Native American trail that once stretched from the ferry landing at today’s Old Fulton Street, running southeast then southwest to where Fort Hamilton is today. The name “Kings Highway” became appended to other old roads in intervening centuries and today runs from Bensonhurst to Brownsville. I have always found the Mother Road’s secrets inscrutable, and hoary with the lore of the various hordes that have alternately scuttled and raced along its length of several miles.

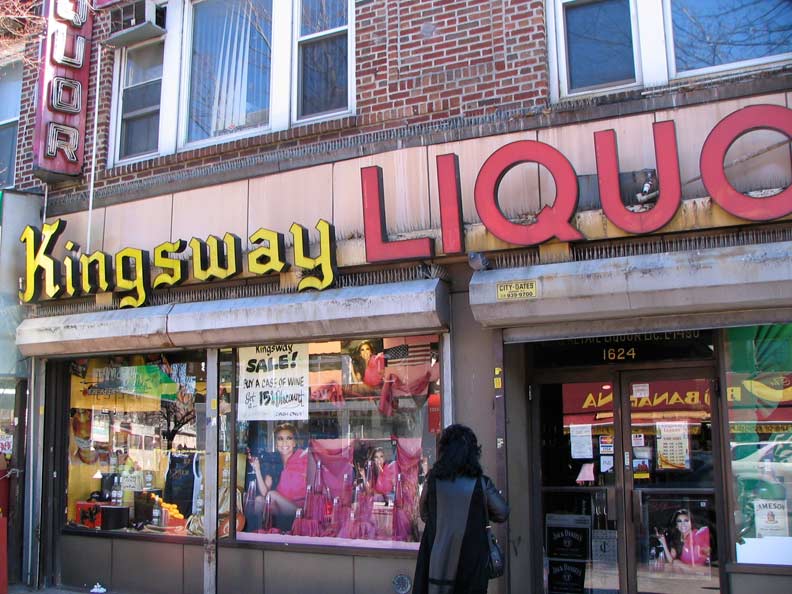

Perhaps there was once a local real estate development called Kingsway along the highway beween Coney Island and Ocean Avenues, which correspond to East 10th and East 20th, with the north-south Brighton Line, a former railroad and now a subway line, bisecting it.

The terra cotta eagle at East 17th and the Highway hints at a lost grandeur; and does the K on the pediment stand for…Kingsway?

No: the building was the Kings Highway Savings Bank from 1923-1971 after which it became part of Ridgewood Savings Bank after a series of mergers and acquisitions.

An unusual trio on the NE corner of East 17th and the Highway, including the Rosa Building on the left. This part of Brooklyn is in good part composed of Russian immigrants who have spread north from Brighton Beach.

East of the junction of Avenue P and Ocean Avenue, Kings Highway becomes an eight to ten lane behemoth, following the old path of Flatlands Neck Road, a colonial era dirt trail. It was widened through what was then mostly farmland as Brooklyn’s borough fathers built out both Kings Highway and Linden Boulevard, anticipating the rising importance of the automobile. Did the auto make Kings Highway, or did Kings Highway make the auto?

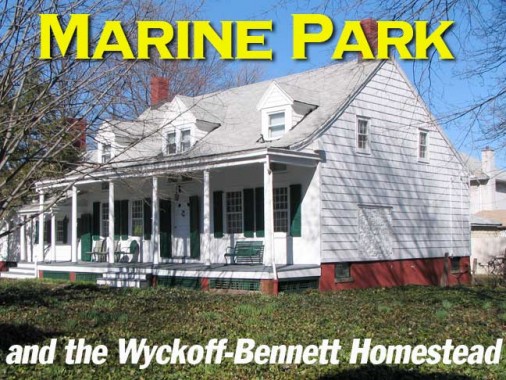

I turned onto Avenue P and at East 22nd, was met by one of Brooklyn’s most fascinating houses: one of its best-preserved Dutch homesteads. It was constructed by 1766 (the oldest inscription found within bears that date) by Abraham and Henry Wyckoff, descendants of Pieter Claesen Wyckoff, who built the much older Wyckoff House on today’s Clarendon Road in East Flatbush in 1652. After the Brits took over New Netherland and surrounding territories in 1664, they had no quarrels with the established Dutch settlers, since Stuyvesant surrendered without much fuss when the British armada showed up in the harbor.

By the 1770s the peaceable era had been long sunder’d by ungrateful Colonists’ insistence upon their crazy idea of independence, however, and red coated British troops were marching up Brooklyn’s Mother Road, which by 1705 has assumed the meet and proper name of the King’s highway, that King being the Restoration monarch Charles II, for whom Kings County was named, and subsequently its Highway. Hessian officers that had occupied the house cavalierly scratched their initials into two windowpanes that have been preserved. In 1835 the house was sold into the Bennett family, which held it until 1983. It remains today as a private residence — it has never become a museum, as did the Claesen Wyckoff house did after it had nearly succumbed to the ravages of age and disrepair.

The garage, constructed in 1899, served as a barn when the house was surrounded by acres of farmland. In 2010, the New York Times afforded a rare glimpse into the interior — including the two historic panes.

By 2011 the farmland is long gone — the Bennetts once controlled land all the way to Jamaica Bay — and the housing stock is pleasant but mostly mundane. I did see this handsome Tudor near Quentin Road, which is nicely covered by ivy in season.

Finally, just before attaining my friend’s apartment on Knapp Street, I passed these two hoary remnants of the Videocassette Age, which was approximately 1984 to 1996, when DVDs swept them to the dumbwaiters, if there were any dumbwaiters by 1996. Many of them valiantly pressed on into the DVD Age, which ended about five years ago when Netflix began delivering images directly to televisions. (The next innovation is tattooing retinas with receptors that will receive direct video transmissions).

Coyal Video, on Avenue U and Coyle (get it?) was an offshoot of the now defunct chain Royal Video.

I still have my Galaxy Video ID card. I also use a VCR, land line phone and answering machine and keep my pockets well stocked with quarters for when I can find a working public phone.

And here’s a vintage 1976 Bicentennial Hydrant.

4/7/11