New York is full of Unions — not only labor unions, but streets and squares called Union. While Manhattan’s Union Square was named in the 19th Century for the encounter of Broadway and Bowery Road (now 4th Avenue), the lengthy routes Union Avenue and Union Street in Brooklyn, Union Street and Turnpike in Queens, and Union Avenue in the Bronx are so called for an honorific for the United States of America not often used these days … the “Union.”

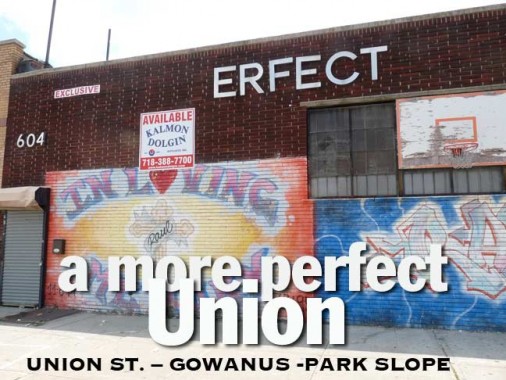

Today’s walk took me down Brooklyn’s Union Street from the area surrounding the Gowanus Canal to Prospect Park, which interrupts its eastbound progress for several blocks. Union Street resumes again at Washington Avenue, proceeding through Crown Heights to Rochester Avenue, and then, unusually, continues again in a north-south direction from East New York Avenue to East 98th in Brownsville…

At Bond Street and Union is a lengthy, two story slope-roofed building painted green, and the small sign on the door simply calls it “The Green Building.” However The Green Building’s website is helpful about the building’s history: it was built in 1889 and was a brass foundry until 1987. Its present occupant is as an event space for commercial shoots, films, dance and theater performances, and corporate events. I haven’t been inside, but the website’s description sounds interesting:

Rustic modern, industrial chic…whatever you call it, the Green Building’s main room is gorgeous. Featuring original brick walls, soaring exposed beam ceilings, four beautiful chandeliers and a roll-up gate that can be kept open on warm nights … A hidden door located within the coat check leads to two beautifully-appointed, 1920s-inspired private rooms which can be used as a talent holding area, bridal dressing room or your very own VIP bar.

Brownstoner says the building dates only to 1931.

Name that truck! Parked outside was what is apparently The Green Building’s delivery vehicle, a vintage Ford truck. A 1928 according to the registration sticker.

The Union Place Inc. Warehouse Outlet, on Union between Bond Street and the Gowanus Canal, features several prime pieces of kitsch available, such as cherub-festooned fountains, arts and crafts roosters, and brass mermaids.

ForgottenFan Carol Gardens: I think the garden statuary is not from the Warehouse outlet, which always sold clothes. I’m pretty sure there is a branch of Horseman’s Antiques (Atlantic Ave and NJ) that opened up behind the yellow door on the right.

The Union Street Drawbridge, the northernmost of the five vehicular bridges that cross Gowanus Canal, is classified by the Department of Transportation as a double leaf Scherzer rolling leaf bascule bridge. It is 109 feet long, 56 feet wide and first opened March 4, 1905. The bridge seems rickety and fragile — it is scheduled for a major renovation in 2017, but it seems as if the work should begin before that. Its twin bridge, the 3rd Street over the Gowanus, opened a few weeks later in 1905. This bridge seems to lose out a little in Brooklyn lore to the Carroll Street Bridge, a rare retractile bridge that dates to 1889. It can be seen in the last photo.

It’s hard to imagine it, as the Gowanus Canal has not been a fresh creek for about a century and a half, but it was originally a natural inlet from Upper New York Bay that seeped into what was South Brooklyn and is now Cobble Hill, with narrow tributaries and rivulets that fingered their way into surrounding areas. That all changed when developer Edwin Litchfield formed the Brooklyn Improvement Company in the 1850s, charged with the task of dredging the creek, straightening it and making it navigable as a canal for, at first, tall masted sailing ships, and later ironclad industrial vessels.

From my Gowanus Canal page (I cirumambulated the canal in November 2005, when the smell was tolerable):

With the creation of the new waterway, barges brought in sandstone from New Jersey that was used to build the beautiful brownstones that today still line the streets of surrounding Boerum Hill and Park Slope. Unfortunately the buildup of the area contributed to the pollution of the canal, which would go on for over a century: the surrounding area’s raw sewage would be pumped directly into the canal, and the new gasworks, coal yards and soap factories along the canal’s length also dropped tons of pollutants directly into it as the years went by. As early as the 1880s the canal was foul and miasmic and its color had changed to a dark Pepto-Bismol shade, prompting locals to call it “Lavender Lake.”

In the 2000s, the flush pump (which was first built in the 1910s) was repaired and the Canal began to become somewhat cleaner and clearer, with some wildlife returning to it, but by 2011 the pump was broken again and the Canal had reverted to its foetid state. In the go-go real estate boom of the early part of the decade, there were grand plans to build expensive apartment buildings along the canal and create a San Antonio-like Gowanus Canal riverwalk. With the economy slumping for three years as of 2011, the plans will have to wait, though the flush pump is under repair again.

There are worlds within worlds of miasmic ichor that meet the nostrils of intrepid Union Street Bridge crossers. It’s unwise to lean too far over the railings — the shudder of a passing truck might catapult a luckless walker into the Canal, and the penalty would be certain death and no guarantee of a recognizable corpse. Meanwhile, looming in the skyline is the Wyckoff Houses and behind them, One Hanson Place, now Brooklyn’s 2nd-tallest building, the former Williamsburg Bank Tower. In the foreground is a painted sign for the Conklin Brass & Copper Company (see the Gowanus Canal link above).Inkhead is a well-known graffitist whose tags have been seen throughout NYC.

When Brooklyn worked. National Packing Box Factory, Union Street and Nevins. The painted lettering has held up well for over a century.

James H. Dykeman’s box factory occupied this building on Union Street in Carroll Gardens. Dykeman “was a carpenter by trade who established himself in the box business in 1877,” according to The Disston Crucible, a Magazine for Millmen. “Two large buildings occupy the whole block at Union, Nevins, and Sackett Streets, the fourth side of the property facing the canal, making it possible to bring lumber to the mill very economically,” the article states. Ephemeral New York

Union Street houses between Nevins Street and 3rd Avenue

On Union Street there’s a sort of subgenre of the funerary industry. We will all spend an awfully long time in caskets, and they have to come from somewhere — I’m glad Brooklyn has casket manufacturers (I saw a faded painted ad for another one on Rockwell Place, but that one had long vanished). Awhile ago during one of my interregnums between jobs — they come frequently — I think this was 2000 — I scored a temp job typesetting those glossy prayer cards that you get at wakes. I didn’t find it fulfilling and left after a short time. That was on Union Street by the canal, too.

The company was founded in 1931 by Thomas Pontone and was more recently acquired by the larger Milso Industries, which is the name on the trucks you will see carrying the coffins out of the low brick buildings in Gowanus and to their customers. But the buildings haven’t changed, they’re still ramshackle and a bit ominous. You might find yourself lingering there, watching the boxes come out in bunches, and wondering who will lie inside them. Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York

I wonder if the long-vanished George Driscoll knew that, by chance, his name would still be emblazoned over the building where his business was located a century or more later.

The 2 Toms restaurant still has exactly the same facade it did when I rode by on the (now nonexistent) B37 bus in the 1960s and 1970s.

Fresh from thoughts of the inevitable sepulchral abyss, my ears were then accosted by an insistent pounding as I crossed Third Avenue, and confirming the well-known premise that Anything Can Happen in Forgotten NY, I had stumbled on one of Brooklyn’s few retailers of African drums.

Senegalese-born Ibrahima Diokhane has a passion: drums. His store, Keur Djembe (which means: “House of Drums” in Wolof) is filled to the brim with djembes and other African drums, which he handcrafts on the premises. Made of authentic materials –imported woods, animal skins, shells, and other traditional pieces — his creations will entice both novices and experienced drumming-circle types … You’ll find classes for kids and adults, repairs, and information about drumming circles here. –Ellen Freudenheim, Brooklyn: The Ultimate Guide to New York’s Most Happening Borough

As Union Street enters Park Slope it begins to change character from manufacturing, or former manufacturing, toward residential. The Union Street BMT station opened on 4th Avenue in 1915, and, along with the now-vanished 5th avenue El (closed in 1940) served the north side of Park Slope. For decades, 4th Avenue was dominated by gas stations and auto repair shops (and the occasional apartment building) but in the go-go early 2000s, a number of expensive high-rise apartment buildings sprang up, as well as restaurants and bars.

For much of its length 4th Avenue has the subway grate at the center median. Approaching its northern end at Flatbush Avenue, the eternal, priapic Williamsburg Bank Building, or One Hanson Place, looms into view. The building also appears to be flipping the bird to the poor punters who can’t afford apartments in it. I am familiar with it as the House of Pain since I had two oral surgeries done there.

I took note of the 2-story residence painted a bright, robins’ egg blue between 4th and 5th, on Union.

Adaptive reuse on the SW croner of 5th and Union is a bank building (hasn’t been a bank for so long, I forget which bank) that has become a gym. Across the street Brooklyn Industries clothing store occupies the storefront of a century-old brownstone building.

All through the 1970s and well into the 1990s, 5th Avenue was lined with burnt-out wrecks reminiscent of the South Bronx. The buildings were skeletons. Even after the rest of Park Slope “gentrified” in the 1980s, 5th remained resolutely untamable. Gradual change came. A Pathmark supermarket was built in 1980, and a bistro, 200 5th Avenue, appeared soon after that. But the recovery didn’t kick in until the late 1990s and into the 2000s; even today, you will find a couple of abandoned buildings along northern 5th.

Written on a wall on the SE corner of 5th and Union, next to an ice cream parlor, is Max Ehrmann’s “Desiderata”. It’s much parodied and made fun of, but most of its sentiments parallel my own. Though it was written in the 1920s there has been confusion about its age and authorship:

Around 1959, the Rev. Frederick Kates, the rector of St. Paul’s Church in Baltimore, Maryland, used the poem in a collection of devotional materials he compiled for his congregation. (Some years earlier he had come across a copy of Desiderata.) At the top of the handout was the notation, “Old St. Paul’s Church, Baltimore A.C. 1692.” The church was founded in 1692.

As the material was handed from one friend to another, the authorship became clouded. Copies with the “Old St. Paul’s Church” notation were printed and distributed liberally in the years that followed. It is perhaps understandable that a later publisher would interpret this notation as meaning that the poem itself was found in Old St. Paul’s Church, dated 1692. This notation no doubt added to the charm and historic appeal of the poem, despite the fact that the actual language in the poem suggests a more modern origin. The poem was popular prose for the “make peace, not war” movement of the 1960s.

When Adlai Stevenson died in 1965, a guest in his home found a copy of Desiderata near his bedside and discovered that Stevenson had planned to use it in his Christmas cards. The publicity that followed gave widespread fame to the poem as well as the mistaken relationship to St. Paul’s Church.

As of 1977, the rector of St. Paul’s Church was not amused by the confusion. Having dealt with the confusion “40 times a week for 15 years,” he was sick of it.

This misinterpretation has only added to the confusion concerning whether or not the poem is in the public domain.

By the way, Desiderata is Latin for “Things to be Desired.” Fleurdelis

The blocks of Union Street from 5th Avenue to Grand Army Plaza are not landmarked, but they contain the eclectic brick and brownstone architecture for which Park Slope is known.

The gang’s all there at Rose Water, a bistro on Union just west of 6th Avenue, the residential filling between the two commercial Park Slope slices of bread, 5th and 7th Avenues.

Across from the restaurant is a mosaic sidewalk tree barrier reminiscent of, but with not quite the panache, of East Village mosaicist Jim Power.

Normally I pass maternity stores by, but note the stained glass work, including the house number, on the NE corner of 6th and Union. The stained glass was installed in 1976 by local craftsman Peter Romano. [courtesy Here’s Park Slope]

Dixon’s Bike Shop, which shares its building with a yoga parlor a couple doors away from a food co-op in a quintessentially Park Slope circumstance, has an interesting building mural a few doors down.

FDNY Squad Company #1, 788 Union Street, lost twelve men on 9/11/01. Sculptors Rick Boswell and Nyal Thomas Jr.’s “Out of the Rubble” was dedicated 3/11/2002.

The carving, titled “Out of the Rubble,” depicts three firemen erecting a flag in the rubble of the World Trade Center after the Sept. 11 terrorist attack.

“The sculpture is unbelievable,” [Squad One Firefighter Eric] Lynch said. “We’re extremely glad he brought it all the way out here.”

Squad One members were among the first firefighters to respond to the attack on the center’s twin towers.

…Thomas, a former fire chief … began carving his tribute in October from an 8,000-pound piece of old growth Sitka spruce. He left Florence with it Feb. 23, 2002, towing it on a flag-bedecked flatbed trailer.

When Thomas left Florence, [Oregon], he didn’t know where his creation would end up but he had faith someone in New York would take it. Along the way, he and fellow carver Rick Boswell of Montana traveled as far as St. Louis and visited 87 local fire departments to show off the carving and ask for support for their trip. Eugene, Oregon Register-Guard

Unlike a traditional supermarket, food co-ops are owned and operated by their own customers and require participation by their members in the actual labor and management of the market in accordance with agreed-upon principles. At the Park Slope Food Co-op, unlike others that have sprung up around the city, only members can shop there and all members are required to put in at least a couple hours a week working there. This requirement can lead to some awkwardness, as described by the webmaster of F’d in Park Slope. [Part 2, same story]

More samples of Union Street’s variety of architecture; attached brownstones from 889-893 between 7th and 8th Avenues, and the corner Queen Anne-style mansion at 70-72 8th Avenue, constructed in 1887 for a Mrs. M.V. Phillips.

This part of Union Street ends at Grand Army Plaza at the northern end of Prospect Park. Monuments, a memorial arch and statues, most of which honor Civil War dead, rim the plaza, where Flatbush Avenue, Prospect Park West, Vanderbilt Avenue, and Eastern Parkway all meet. Brooklyn’s main library branch and high rise apartments also surround the space. On Saturdays, the north end of Prospect Park is taken over by a farmer’s market.

East of the park, Union Street continues through Crown Heights and into Brownsville, but I’ll leave that for another time.

7/3/11