If you have never heard of Finn Square, that’s perfectly understandable. In NYC parlance, a “square” can be any shape, and Finn Square is a triangle in Tribeca formed by the intersection of West Broadway and Varick and Franklin Streets. Officially, there’s no actual neighborhood called Finn Square, but in my opinion there’s enough distinctive architecture and unusual surviving artifacts to designate it as a distinct region.

On the Lower West Side of Manhattan, there are two separate street grids, one that hews to a general east-west-north-south orientation (though Manhattan Island runs a little northeast against true north) and a diagonal grid that begins just north of Canal and runs north to West 14th. This grid is positioned so it runs perpendicular to the Hudson River shoreline. (There are variations in orientation of this diagonal grid in he West Village, especially between Christopher and Bank.)

Where these two grids meet, there are interesting intersections and streetscapes. West Broadway acts as the barrier between the two from Chambers north to Canal, with 6th Avenue dividing the two grids from Canal north to West 8th since it was extended south from Carmine Street beginning in 1928.

Finn Square actually honors two Finns. The first was a Tammany Hall politician, Daniel E. Finn (1845-1910), known as “Battery Dan” for his success as an assemblyman in the First District for helping block a plan to build piers along the west shore on Manhattan in Battery Park. The piers were not built and Battery Park remains to this day a much-needed open space relief from the beetling towers of lower Manhattan. As a judge, Finn was known for protecting the public against Police Department excesses.

Although in actuality Finn Square was named for “Battery Dan,” officially it is named for his son, Philip Schuyler Finn, a member of NY’s Fighting 69th Regiment, who perished in World War I. The square itself was created shortly after the war, when Varick Street was given a southern extension past Franklin Street to meet West Broadway.

My walk began at the Canal Street station on the IND 8th Avenue (E train) from whence I walked south through Tribeca Park and the American Thread Company Building at West Broadway and Beach Street.

WAYFARING MAP: FINN SQUARE

The first building that caught my eye was this 2-story building at West Broadway and North Moore (one of the few places in NYC where streets prefixed “west” and “north” intersect) that I know nothing about, but must have an interesting history, perhaps as a stable.

Hook & Ladder 8

Hook & Ladder 8, at North Moore and Varick, is more popularly known as the “Ghostbusters firehouse” as this was the firehouse where the ambulance used by the spook-chasing comics in that 1980s 2-film series was headquartered. It is a functioning firehouse, though budget cuts had the 1865 masterpiece on the chopping block in May 2011. The next month, its continuation of service was announced.

Scouting NY revisits Ghostbusters scenes

N. Moore

There are still well-read West Villagers and Tribeca-ites who insist that N. Moore (which always appears rendered like that on new and old street signs — never North Moore) was named for Columbia College librarian from 1842-1849. Columbia later moved uptown to Broadway and 116th, of course, where it is presently devouring the west end of Manhattanville.

N. Moore, however, is named for a Moore, but not Nathaniel. It was named for his uncle, Benjamin Moore (1748-1816), who was Trinity Church rector, Episcopalian bishop, and president of Columbia College from 1801-1811. In the early 1800s, Trinity Church owned much of western Manhattan, and when streets were created, church officials named them for prominent church officials, and Benjamin Moore took his place among them. This Benjamin Moore had nothing to do with the other prominent Benjamin Moore who began a paint company in 1883.

There was, ah, one small hitch when it was time to honor Benjamin Moore. Manhattan already has a Moore Street near the Battery, named for nearby docks in its original Moor Street spelling. So, as the location was generally north of there, the N. was affixed to the Moore.

Varick, for its part, was named for Colonel Richard Varick, a secretary to George Washington. He was NYV mayor beginning in 1789.

Colonel Varick was one of the most interesting figures in our early history. He was General Washington’s private and military secretary during the latter part of the Revolution and a member of his household, and previous to that had acted in a like capacity for General Philip Schuyler. Later he was appointed inspector-general at West Point, on the staff of Benedict Arnold, and he held that position until taken into the personal service of Washington. In early life he married Maria Roosevelt, the eldest daughter of Isaac Roosevelt, the president of the Bank of New York and owner of the finest residence on Queen Street. After the war he became mayor of New York, and was in office during the city’s brilliant period as the seat of government, successfully guiding its corporation into the new century. Historic Houses of New Jersey, W. Jay Mills

The 1st Precinct Stables on Varick between N. Moore and Ericsson Place had been for decades home to NYPD equines, but its closing was announced in May 2011 to make way for a #1 World Trade Center command center.

The Little White House

Because of the miracle of landmarks preservation, the designated #2 White Street, at the northeast corner of West Broadway, has survived since 1809. It was constructed that year for a Gideon Tucker, owner of the Tucker & Ludlam plaster factory. It’s one of the few Federal Style row houses remaining in lower Manhattan. A few others that were moved from their original location during construction of Independence Plaza can be seen on Harrison Street west of Greenwich.

1966 Landmarks Preservation Commission Report

Matera Canvas, which distributed boat covers, tarpaulins, tote bags, awnings, aprons at 5 Lispenard Street, originated in 1907 and was still in business in 1990. The storefront used to feature a nifty clock.

Two more views of #2 White. There is a clothing store on the ground floor, and there is a story behind that, too.

The corner store at what the owners call 235 West Broadway (which is apparently a sexier address than #2 White) is officially a J. Crew Men’s Store, and a glance in the windows will make apparent that it’s a haberdasher. In 2011, it’s fashionable to not hang an identifying sign whatever–you have to go in to find out what the name is.

Signs of the store’s former use are still very much in evidence…

In 1941, Leonard Hecht opened a liquor store on the ground floor that continued in business until the 1990s. The Liquor Store Bar then took it over, and then J. Crew in the 2000s. Throughout, the old liquor store signs have been permitted to remain in place.

Of the Liquor Store Bar, New York Magazine had this review:

It lacks leather banquettes and attitude at the door, but this tiny tavern is quite an attraction. On any given night, the little wooden cocktail tables are packed with locals seeking refuge from haughtier drinking establishments nearby. The cordial bartenders serve up pints of beer and generous $8 martinis to an attractive after-work crowd that cozies up to the etched oak-and-brass bar during the week. On the weekends, a fashionable coterie packs the place to standing-room capacity, making it the busiest spot in the area—and leaving competitors’ velvet ropes to do little more than swing in the wind. Tisa Coen

A cordial is a nonalcoholic beverage made from the flowers of the elderberry plant.

Etched-glass signs like this are not seen as often as they used to be.

Cognac is a brandy made in the French region of the same name.

Amazing that artifacts of a store going back to 1941 are still in place.

226 West Broadway

This is a notable 1912 building featuring a gleaming white terra cotta front. Formerly the FDNY High Pressure Service Headquarters, it was later transferred to the Dept. of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity. I am attracted to gleaming white terra cotta as if it were pizza.

This sort of letter chiseling, which is rarely done today, must have been very difficult to do. Notice the little triangles between the words, done as just an added fillip or decoration. Early mosaic subway signs from 1908-1928 feature them as well.

From the 1991 NYCLPC Historic District Designation Report:

This four-story, twenty-five-foot wide municipal office building, located midblock, was erected in 1912 for the Department of Water Supply, Gas, and Electricity as a headquarters for the repair company of the high pressure fire service system. It was designed by Augustus D. Shepard, Jr., an architect who spent much of his career working in the Adirondacks.

The building, faced in cream-colored glazed terra cotta, has characteristics of both an industrial workshop and an office building. The base has a center vehicular opening flanked by pedestrian doors. The Secessionist-inspired ornamentation of the building features one-of-a-kind forms of hydrants, pipes, and valves — the iconographic representation of the work of the agency, the name of which appears in a panel at the second story. The upper facade is almost a window wall, with grouped two-over-two-over-two triple-hung wood sash, divided into bays which correspond to the divisions of the base; iron balustrades edge shallow balconies at the fourth story.

A curved parapet frames a sculptural of the seal of the City. The western elevation has a shallow skylight-lit extension at the first story and two or three windows at each story above. The building was erected on a city-owned lot on which had stood a wing of Ward School No 44, located at 10-12 North Moore Street. In 1967 this building was occupied by the Department of Welfare Maintenance Shop; it is currently in private ownership.

Valve sculpture

Pipe sculptures

Stylized hydrant sculpture. These amazing details and representations are found nowhere else in town on any other pumping station. Amazing stuff.

Moving on to the NW corner of Varick and Franklin. It’s hard to find a bad building in the whole of Tribeca and this intersection features one of the best. Known as 140 Franklin, this massive Romanesque building was completed in 1887 for a wrapping paper manufacturer; the architect was Albert Wagner, whose most famous work is the Puck Building at Lafayette and East Houston.

The Franklin Street IRT 7th Avenue Line (#1 train) entrance is on an open plaza just north of Finn Square, so a metallic kiosk was built in the 1990s during station renovations to shield passengers from the rain when entering and exiting. The platform mosaics feature unusual paneling and floor tiling that are unique to the system.

The Square Diner has been on the NW corner of Varick and Leonard (it’s now the first address on Varick) since 1945. It is a Kullman diner with a slanting roof, which disguises it somewhat from its early days as the Triangle Diner, when it looked somewhat more classic.

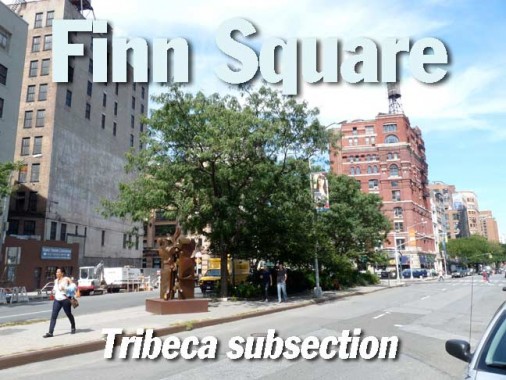

Finn Square. The side wall of the building at left is testimony to the Varick Street extension south to West Broadway (foreground) in 1918. At the rear is an 1882 loft building (George W. DaCunha, architect). The trees were plated in the previously barren triangle in the 1990s.

The artwork installation at the tip of the Finn Square triangle by Bill Bennett is called 911 (from the Lexeme Series); completed in 2006, it is exhibited here from May to October 2011. The somewhat macabre work is meant to depict the Twin Towers in flames. (Much great art has come from tragedy, but a local tragedy wouldn’t make me want to produce art. Picasso and other giants have thought differently.)

Meant to commemorate the 10th anniversary of 9/11, the Lexeme Series began as a way for Barrett to process and talk about the heartbreaking events of September 11, 2001. It includes works in fabricated bronze, stainless steel, and an 11-foot-high Carrara marble piece that was carved in Carrara, Italy, and shown in Zell, Germany. In their own unique way, all of the Lexeme sculptures incorporate the presence of the World Trade Center. With this particular sculpture, Barrett aims to present the idea that life, and positive and creative energy continue to prevail.

Bill Barrett has been a member of the Tribeca community for over 40 years. His studio is just blocks from the installation site. He has exhibited widely throughout the country. NYC Parks

The New York Law School‘s glass tower addition (2009, SmithGroup) dominates the SW corner of West Broadway and Leonard. There are four underground floors.

The school was founded by Columbia law school professors in 1891. The main school is at nearby 57 Worth Street.

A cast and wrought iron Twinlamp stands at the SW corner of 6th Avenue and Walker Street. It’s listing to the starboard side a little, and its top finial has been missing for awhile.

Twins were the first genre of cast iron streetlamp to appear in NYC streets. They were first installed (in a different style) on 5th Avenue beginning in the early 1890s, and 5th had been their chief bastion until 1965, when a new genre of double Deskeys, used only on 5th, replaced them.

Other than that, the Twins were used relatively sparingly, though they did turn up on broad roads with central dividers, like Queens Boulevard and, I believe, Bruckner Boulevard in the Bronx.

This Twin was installed no earlier than 1928, the year 6th Avenue was extended south into Tribeca. I don’t have any photos of this stretch of 6th from that era, so I wonder if this was a one-shot, or lower 6th was lit by a flock of Twins.

Now that I have an 18x zoom, I can get in pretty close to the detailed ironwork without a ladder.

In the 1980s, this pair of bright yellow light Bucket lights replaced the pair of Gumballs that had likely been on the post since the 1940s.

I wonder what flower the pair of central “rosettes” is meant to represent.

This is as close as I can get.

I am aware the designs on the bases and shafts of NYC’s castiron lamps are meant to resemble acanthus leaves, which were used extensively in Beaux Arts architecture.

This traffic is representative of 6th Avenue and other north-south routes here, as vehicles scramble for the Holland Tunnel.

White Street Fronts

To complete the brief Finn Square walk I went east on White Street to take a look at some buildings that caught my eye. Though fine examples can be found north of here, this is the northern end of the Tribeca cast iron front district, from a brief era in the mid to late 19th Century when it was thought prudent to fireproof buildings by installing elaborate metal fronts.

White, and the surrounding streets, are part of the Tribeca North Historic District, designated in 1992. I don’t know much about this building on the north side of White, but its date of construction, 1866, is displayed on the cornice, and the ghostly remains of the word carburetor can be seen above the entrance. Before the auto era, what were carburetors for?

Wood’s Mercantile Buildings (1865), 46-50 White, “are handsome examples of the Italianate commercial palaces faced in Tuckahoe marble that transformed the streets adjacent to Broadway just north of City Hall into a prime business district in the 1850s and 1860s. The two buildings, designed as a single unit, have cast-iron shop fronts and are crowned by an unusual pedimented cornice emlazoned with the name and date of the buildings.” —Guide to New York City Landmarks, ed. Matthew A. Postal

This building has been individually landmarked by the LPC.

Nudged between the cast iron and marble fronts on White Street is #49, a structure that serves to set off the rest of the block, and perhaps the rest of the district, Synagogue For The Arts.

Tribeca was a very different place in the 1960s, when William Berger designed the Civic Center Synagogue at 49 White St. For one thing, the architect could insert his unique, flame-shaped creation onto a block of 19th-century loft buildings without a thought to what the Landmarks Preservation Commission would say. Tribeca’s historic districts were still decades away.

The synagogue did not need space for a Hebrew school because there were few families in the area, just workers in the nearby warehouses and municipal offices who needed a place to pray during the day. And, of course, it was some 30 years before terrorism would happen here.

The building’s expansive plaza—above which the synagogue’s curved, white marble facade appears to float—seemed to offer the solution. Wired New York

You might be surprised to hear it from me, but there’s a place in the world for Modernist buildings and innovative design in a city that has become increasingly stolid and boring in its architecture the last couple of decades. I’m glad this was built before Landmarks Preservation could say NO.

Unlike the intersection of W. Broadway, Varick and Franklin, where Varick begins a northern run before becoming 7th Avenue South, designated Finn Square and given art and landscaping, the triangle at Church, White and 6th Avenue giving rise to a major city artery remains unnamed and rather barren. The expensive Tribeca Grand hotel faces it, out of the photo on the right side.

Souces: Tales of Old Tribeca, Oliver E. Allen, 1999 Tribeca Trib. The columnist’s book is an indispensible guide to neighborhood history. Out of print now but should be easy to track down.

2012: more on Finn Square from the NY Times’ Christopher Gray

9/25/11