In the mid-19th Century Manhattan was getting so crowded (by 1845 the island was fully built up south of about 42nd Street) that it was running out of cemetery space. The two largest cemeteries had been developed by Trinity Cemetery, in the churchyard adjacent to its ancient Broadway and Wall Street location, and uptown in the furthest reaches of civilized Manhattan territory, the wild north of 155th and Broadway.

By the 1840s Brooklyn’s largest cemeteries, Green-Wood and Most Holy Trinity, and Woodlawn in the Bronx were accepting interments; and in Staten Island there was Moravian, developed in the 1760s, and myriads of smaller cemeteries.

Queens, too, had dozens of tiny burial grounds scattered around, many dating to the mid-1600s. In 1847 the Rural Cemetery Act was passed, prohibiting any new burial grounds from being established on the island of Manhattan. Presciently anticipating the legislation, trustees of the old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street in what is today known as Little Italy began buying up property in western Queens. Calvary Cemetery, named for the hill where Christ was crucified, opened in 1848. The original acreage had been nearly filled by the late 1860s, so additional surrounding acreage was later purchased to the east.

The original Calvary Cemetery lies between the Long Island Expressway (formerly Borden Avenue), Greenpoint Avenue and 37th Street, Review Avenue and Laurel Hill Boulevard. New Calvary, in three divisions, is west of 58th Street (formerly Betts Avenue) from Queens Boulevard south to 55th Avenue. Smaller, pre-existing cemeteries were part of the original acreage, and were then surrounded by Calvary.

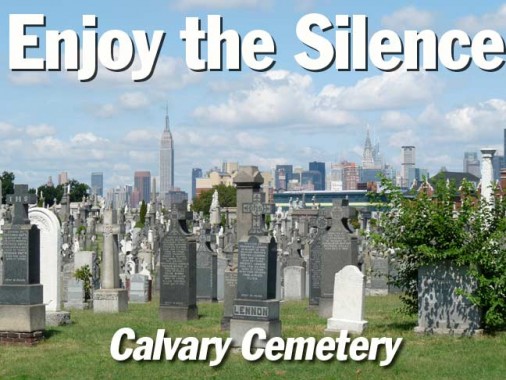

My usual cemetery of choice for exploration to satisfy my thanatophilia has been Green-Wood in Brooklyn, due to its accessibility, but I figured the time has come to see more of NYC’s more prominent burial grounds. I have been to Woodlawn once, and figure to return again for a possible ForgottenTour. Moravian in Staten Island, the resting place for generations of Vanderbilts, is a probability in Staten Island. But today’s quarry was Calvary. It is not a burial park, as Green-Wood or Woodlawn were designed to be; rather, it was a place where, when you’re dead, to get yourself buried, as the feared showbiz columnist J. J. Hunsecker would put it. Despite its no nonsense quality (original interments cost families seven dollars, and family members often dug the graves themselves) Calvary sometimes has a surrealistic atmosphere, with the beetling towers of Manhattan and Queens the backdrop.

Along for the journey was Newtown Pentacle master Mitch Waxman, who has made Newtown Creek and what surrounds it his spare time’s complete focus. He has done extensive research on the cemetery and who and what is there. We set off in mid-July under the Burning Thermonuclear Eye of God Itself.

We met at Woodside LIRR and made down Roosevelt Avenue then Greenpoint Avenue toward the cemetery. I kept my eyes peeled for old school signs like this one at a drugstore, which uses the old vessel with a pestle motif. Since I am an ancient graybeard now, I remember when drugstores had these glass pitchers or bottles full of colored liquid in the window. Cough syrup?

When you see an overhanging vinyl awning sign, walk under it and look under the awning — hidden treasures, like this Wetter’s (?) sign may await you.

If you have been following FNY for awhile now, you know brick architecture is my favorite type–to me you can’t go wrong with red bricks. I have always admired pre-war apartment buildings with brick exteriors as well as factory buildings that have been converted to apartments. I live in a garden complex comprising of two-story brick buildings on a hillside that I had my eye on a dozen years before I bought in.

Here at the entrance of Calvary Cemetery at Greenpoint and Gale Avenues is a Queen Anne gatehouse building with a hexagonal, peaked tower. It’s a near-perfect building, constructed in 1892 (the architect is unchronicled). This entrance building and all of Cavalry have not been landmarked, and, being in Queens, will probably not be.

I do not know if the practice at Mass at 10AM on Saturdays is still in effect (we will see the chapel later).

The actual gate of Calvary is emblazoned with the name St. Calixtus. Calixtus, or Callistus I, was an early pope (217-222) and was martyred (allegedly by being thrown down a well) by the Roman Empire for his beliefs. His predecessor, Pope Zephyrinus, entrusted to him the care of the burial vaults along the Appian Way where many popes during the 3rd century were interred, as rediscovered in an archeological expedition in 1849. He is the patron saint of cemetery workers.

Newtown Firefighter

Among the first gravesites of note you encounter after entering Calvary is that of Charles Keegan, a Brooklyn firefighter killed in the line of duty while fighting a blaze at Locust Point (the long-lost locale is at Meeker Avenue where it meets Newtown Creek), caused by a lightning strike at the Sone and Fleming Kings County Oil Refinery on 9/15/1882). Explosions associated with the blaze claimed the first Penny Bridge; Keegan and fellow firefighter Stuart Deane suffered grisly deaths, according to the New York Times account.

This gravesite is where you find Michael Degnon and his family. After forming the Degnon Construction Company in Cleveland in 1895, Degnon, whose chief line of construction was in railroads, moved his headquarters to New York in 1897. The Degnon Company built many of the IRT’s early subway tunnels in Manhattan and Brooklyn from 1904-1908; the Steinway tunnels originally meant to carry trolley cars but later fitted for subways; what is now known as the PATH tunnel under 6th Avenue; and much of the original Pennsylvania Station. Degnon also built a now-defunct railroad serving several warehouses and businesses in Sunnyside that connected to the nearby Sunnyside railyards, as well as many of the warehouses themselves which are now home to schools and the International Design Center. Some of the Terminal’s early clients were Sunshine Biscuit Company, Packard Automobile Company, American Ever Ready Company, and American Chicle Company. Of course, the rising cost of doing business in New York forced all of these companies to find other cities in which to manufacture, and the Degnon tracks in Sunnyside were defunct by the end of the 1980s. Degnon’s railroad works around the country are also numerous.

Taxi! These gravesites are all associated with one family. Limestone and marble sculpture, as so much of the sculpture in the cemetery happens to be, is especially vulnerable to attacks by wind and rain. Add to that the presence of the nearby Queens Midtown Expressway and Newtown Creek, possibly the most fetid, miasmic waterway in the Northeast (second only, perhaps, to the Gowanus Canal) and you have the recipe for severe sculptural disfigurement and, at times, decapitation.

Feel free to think of mausoleums, or mausolea, those boxy, columned buildings in cemeteries that hold burial vaults of (most often) well-to-do families, as Cracker Jack boxes — if you look inside, you will get a prize: a beautiful religious-themed stained glass window. And, you never know, some of them may be Tiffanys.

Bantry Bay Tavern, Greenpoint Avenue and Bradley Avenue, and the County Cork Association speak of a tenuous Irish presence in Blissville, which is actually larger in neighboring Sunnyside. Irish immigration to the USA has ebbed and flowed in response to Ireland’s economy, way up in the 1990s but way down now.

American Composer

Joe Howard (1878-1961) was a prolific songwriter in the late 19th and early 20th Century. While he didn’t rise to the heights of an Irving Berlin or Oscar Hammerstein, he appeared in vaudeville as early as age 11 and wrote dozens of hits and songs in Broadway musicals.

Cartoon fans will recognize Michigan J. Frog’s rendition of Howard’s 1899 “Hello Ma’ Baby”:

And Joe Howard’s “I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now,” written in 1909, has been heard in dozens of versions, like Billy Murray’s hit 1910 recording

The song was revived in the late 1940s by Perry Como and Ted Weems and here, Dino takes a whack at it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=56V_RjJhCQs

Other names from showbiz interred in Calvary include Tess Gardella, who played the first Aunt Jemima in 1920s productions of Show Boat, even though she was white; actress/nightclub owner Texas Guinan (“Hello suckers!”; Whoopi Goldberg’s 10 Forward proprietress on Star Trek was named for her) prolific character actors Arthur O’Connell and Joe Spinell, who were in hundreds of TV shows and feature flicks; and Una O’Connor, who screeched and screamed in the James Whale 1930s productions of Frankenstein and The Invisible Man.

A view south toward Brooklyn. The Williamsburg Bank Tower can be seen on the left.

The Brooklyn landmark best seen from the Cemetery, of course, is the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant’s 8 “digester eggs” in Greenpoint, better known as the “shit tits,” which are lit blue at night and have become an actual tourist destination, as well as a backdrop for TV drama settings.

Mitch Waxman entered one of the eggs on tour, and came back out.

Joe Masseria, one of the Mafia’s “Boss of All Bosses” was buried in Calvary.

Masseria’s Mafia Family was the most powerful Organized Crime Family in New York City from the start of prohibition until the out break of the Castellammarese war in 1930. During the Castellammarese war he came into conflict with Salvatore Mararanzano- the leader of the Mafia Family that today is known as the Bonanno Family. Maranzano fought to free his Family and the other Families of Masseria’s tyrannical rule. The Castellammarese war ended with the murder of Joe the Boss in a Brooklyn restaurant on April 15,1931. Maranzano then became the top man in the American Mafia. But his power did not last long — he was murdered in his business office in Manhattan on Sept.10, 1931. His murder was ordered by Lucky Luciano and carried out by Meyer Lansky’s men (Albert Anastasia, Vito Genovese, Joe Adonis and Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, three of whom became prominent bosses, themselves). findagrave

The King Of All Buildings is never more spectacular then when seen from Calvary. There even more striking vistas available elsewhere in the cemetery, when it appears to be rising alone out of a plain full of gravestones.

Calvary Chapel

The centrepiece of Calvary Cemetery is its central chapel (Raymond Almirall, 1895) called a “miniature Sacré Coeur beehive tower” by the AIA Guide to New York City; it resembles the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Paris.

It was also designed as a burial crypt for NYC’s parish priests:

From the architect’s point of view, the most unusual feature is the method of construction of the dome and the groined vault on which it rests, both of which are regarded by experts as feats in reinforced concrete construction. The dome is 40 ft. across and the height from the floor to the lantern is 38 ft. It rises 50 ft. higher from that point and its total weight is 360 tons. The vault has eight penetrations, four large and four small, and both the lining of golden yellow brick and the pink Minnesota sandstone trimmings are held in place simply by adhesion to the concrete. In order to build this dome, it was necessary to build a falsework with all the accuracy of a mould, so that the brick could be laid against the forms, and the concrete with its steel reinforcement placed in the moulds. When the concrete had set, the falsework was removed, and the great dome stood as an imposing architectural crown to the structure, as well as a feat in construction.

The crypts or catacombs are for the burial of the priests of the diocese of New York, under the charge of which the cemetery is maintained. At present, but one section of the catacombs has been completed with accommodations for twenty-four bodies in the concrete niches. But the section can be extended underground in four directions, and at any time an addition for seventy-two more bodies can be made. For a cryptal burial there is a lift set into the floor of the chapel to lower the body to the level of the crypts. Popular Mechanics, as found by Mitch Waxman

Al Smith (1873-1944), was Governor of New York State for four two-year terms (elected in 1918, 1922, 1924 and 1926) and the unsuccessful Democratic standard bearer in the 1928 Presidential race (he lost to Herbert Hoover, but was the first Roman Catholic major-party candidate). The “Happy Warrior” as FDR nicknamed him, championed laws governing workers’ compensation, women’s pensions, and children and women’s labor. He broke with Roosevelt after the latter’s election in 1932, disagreeing with FDR’s New Deal policies. A protegé of Smith’s was an assistant, Robert Moses, who began building NYC’s parks, parkways and expressways systems in the 1920s. After the 1928 election, Smith became president of Empire State Inc., the governing body in charge of constructing the King Of All Buildings.

Other NYC and NYS politicians interred at Calvary include Patrick Jerome “Battle Axe” Gleason, the colorful mayor of Long Island City; High J. Grant, who became mayor of NYC at age 31, the youngest in history, serving from 1889-1892; and Robert F. Wagner I, II and III, a longtime US Senator (1927-1949), a longtime mayor of NYC (1953-1965) and a deputy mayor and President of the NYC Board of Education, respectively.

The aquamarine Citi Tower, which replaced St. John’s Hospital on Jackson Avenue in 1989, competes with gravesite shaft monuments in this view. But as tallness is concerned, on Long Island it is nonpareil. It replaced the Williamsburg Bank Tower as Long Island’s tallest building.

We paused by the gravesite of Esther Ennis. Why Esther? She was the first interment at Calvary Cemetery in 1848. Not much is known of Esther Ennis, though according to legend she died ‘of a broken heart’ at age 29. This stone was placed over 100 years after her death, judging from the styling. This is not the earliest grave in Calvary, though, as we will see.

Another vista of the ESB that includes its predecessor as tallest in NYC, the Chrysler Building at right.

These two stones, near the Ennis grave, date to 1849 and are the original McCoys from that date. Sadly the interred here all died in childhood or teenage years. In the 1840s, gravestone architecture was moving away from brownstone (which actually preserves very well) and toward limestone and marble, which don’t.

Two figures that are illustrative of the deterioration of Calvary’s sculptures.

The sculptures are part of the Mary Frances Connell Memorial, which includes an expansive tableau of kneeling and mourning figures.

Mitch Waxman joined me at Calvary Cemetery’s “death tree” where a number of graves are clustered. The tree apparently gained sustenance from, er, whomever was buried here when it was growing. In a bizarre occurrence, a root appears to reach down into the Boyle grave.

The third-tallest building in the Cemetery, after the gatehouse and chapel, is the Johnston Mausoleum, which is prominently viewable from buses entering the Queens Midtown Expressway; unfortunately, I know nothing about the Johnston who received this monumental tomb, though he must have been a big shot.

In another vista, the Church of St. Raphael, on Greenpoint and Hunters Point Avenues, one of Sunnyside’s tallest buildings, can be seen looking northeast. It was constructed in 1885.

O’Brien Memorial

Atop Calvary Cemetery’s tallest hill is the O’Brien- Pardow Memorial. Patriarch William O’Brien, an Irish immigrant in the Revolutionary era, was a prominent financier, and his grandson, William O’Brien Pardow, was a prominent Jesuit NYC churchman. Let the Newtown Penticleer fill in the minute details.

Looking southwest, toward the Queens Midtown expressway and Kosciuszko Bridge, which is scheduled to be replaced by 2014; real-time, 2030.

Civil War Memorial

Calvary Cemetery’s Civil War memorial is owned and operated by the NYC Parks Department, explaining the maple leaf Parks sign. It’s the only NYC park completely surrounded by a cemetery. While Green-Wood Cemetery Soldiers’ Monument has been newly spiffed and polished, Calvary’s copper is resolutely verdigris’ed.

On April 28, 1863, the City of New York purchased the land for this park from the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and granted Parks jurisdiction over it. The land transaction charter stated that Parks would use the land as a burial ground for soldiers who fought for the Union during the Civil War (1861-65) and died in New York hospitals. Parks is responsible for the maintenance of the Civil War monument, the statuary, and the surrounding vegetation. Twenty-one Roman Catholic Civil War Union soldiers are buried here. The last burial took place in 1909.

This park is one of many public parks that serve as burial grounds. There are burial sites in Fort Greene Park (the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument) and Prospect Park, in Brooklyn, and in Drake Park, Pelham Bay Park, and Van Cortlandt Park, in the Bronx. Other parks throughout the city were once potter’s fields which had no grave markers. Washington Square, Union Square, Madison Square, and James J. Walker Parks in Manhattan and Wayanda Park in Queens were all cemeteries for paupers and drifters.

The monument features bronze sculptures by Daniel Draddy, fabricated by Maurice J. Power, and was dedicated in 1866. Mayor John T. Hoffman (1866-68) and the Board of Aldermen donated it to the City of New York. The 50-foot granite obelisk, which stands on a 40 x 40 foot plot, originally had a cannon at each corner, and a bronze eagle once perched on a granite pedestal at each corner of the plot. The column is surmounted by a bronze figure representing peace. Four life-size figures of Civil War soldiers stand on the pedestals. In 1929, for $13,950, the monument was given a new fence, and its bronze and granite details replaced or restored. The granite column is decorated with bronze garlands and ornamental flags. NYC Parks

Adjoining the Civil War memorial is another, commemorating the NYC 69th Infantry Regiment (“Fighting 69th”), part of the US National Guard. The regiment, founded in 1849, has had a rich history in the Civil War and World Wars I and II.

It is an Irish heritage unit, with many of its traditions and symbols deriving from a time when the regiment was made entirely of Irish-Americans. The regiment’s Civil War Era battle cry was “Faugh a Ballagh,” which is Irish Gaelic meaning “Clear the Way.” This is reminiscent of the cry of the Irish Brigade of the French Army in the Battle of Fontenoy. A World War I era battle cry is “Garryowen in Glory!” Its motto is “Gentle when stroked – Fierce when provoked” in reference to the Irish Wolfhounds on its crest and dress cap badges of 1861. New York City’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade up Fifth Avenue has always been led by the Regiment and its Irish Wolfhounds. In some ceremonies, the regiment’s officers and senior non-commissioned officers carry shillelaghs as a badge of rank. Additionally, it is traditional to wear a small sprig of greenery on ones headgear in combat, as was first done in the Civil War. wikipedia

The regiment is still active, and has fought in Iraq beginning in 2003.

Alsop Cemetery

Richard Alsop’s gravestone, dated 1718, is the oldest in Calvary Cemetery. The Alsop family burial site, in a southern corner of Calvary Cemetery in view of the Kosciusko Bridge, pre-existed Calvary by over a century and was simply incorporated into a Calvary when the land it stood on was purchased by St. Patrick’s. (In nearby Mount Zion Cemetery, you will find the equally old Betts family cemetery. Other unusual cemetery placements are the Drake Park cemetery in Hunts Point, Bronx, and the Quaker cemetery in Prospect Park where Montgomery Clift was laid to rest.

Richard Alsop had been bequeathed the land by his cousin, British immigrant Thomas Wandell.

Hannah Alsop, widow of Richard. Deaths head gravestones are unusual in NYC, since in general, skulls were replaced by angels in the late 1700s. Note that the chiseled lettering on these brownstone markers has held up well for over 250 years.

Several members of the Alsop family were interred here between 1718 and the late 1880s, as well as the family’s slaves, whose graves are unmarked. The family was prominent in Newtown, and married into the Fish family and King family, which produced a NYS Governor and 1816 Presidential candidate Rufus King, whose mansion stands in Jamaica. His wife was neé Mary Alsop. The last of the Alsops died without issue in the 1880s.

Leaving Calvary

The Laurel Hill Boulevard gate is officially the main gate of Calvary Cemetery, but it can no longer be considered the popular entrance since it empties onto one of the grittiest, nastiest and deserted sections of Queens at Review Avenue and Laurel Hill Boulevard, bordered by rail tracks used mostly for freight.

This was once the site of the rickety Penny Bridge, connecting Review Avenue and Meeker Avenue in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and its accompanying Long Island Rail Road station. In the 1800s and well into the 20th Century, when the Penny Bridge was in existence this was indeed the Calvary main entrance, as processions bearing the remains and the grieving made their way over waters already well on their way to being the nastiest in the nation. However, the additions of steamships and heavier vessels made Penny Bridge an impedence to Creek water traffic.

In 1939 Robert Moses arched the imposing Kosciuszko Bridge, named for a Polish compatriot of the American Revolution, over the mighty Newtown. Pedestrian access over the Creek was thereafter limited to the Greenpoint Avenue bridge to the north.

Generations of New Yorkers have pronounced the bridge Kos-kee OS-ko, but Polish is a language in which consonants are not to be taken literally and creative pronunciations abound (just ask Duke University basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski about it — just call him Coach K) and the bridge in original Polish is closer to Ko-SHOOS-ko, but even that is an approximation.

These tracks are usually employed by freight trains, but if you are here at the right time of day, you will see one of the three daily passenger runs that traverse here on weekdays. The Penny Bridge station, which was a clearing of the weeds on either side of the tracks, was finally eliminated in 1998 when the LIRR purchased new equipment that required high platforms, which it was not cost-effective to build here.

For more on Calvary, the Newtown Pentacle is a virtual encyclopedia.

12/11/12