Lower Manhattan…the Tribecas, the SoHos, the NoHos — have become, during the last couple of decades, a wonderworld of high-end shopping, impossible-to-afford residences, and have acheived an aura of sophistication and haute couture, where mink-wrapped socialites exit limos into the boutiques.

Just a generation ago, though, Tribeca didn’t have a name, it was just a nondsecript area south of Canal where cast iron fronts didn’t denote picturesque twee-ness, they were there to stop fires. The area was dominated by loft buildings jammed with dry-goods wholesalers and textile manufacturers. Things were so anodyne that the 20th Century NYC traffic czar Robert Moses wanted to bruit a Lower Manhattan Expressway on an elevated structure on Broome.

I’m not saying one era of Lower Manhattan was better than another, though there were seemingly more jobs for the lesser-skilled in the former era. Neighborhoods evolve and change, rise and fall. As the centuries roll, Lower Manhattan will be up and down.

There are places where Lower Manhattan’s old grittiness pokes through. Cortlandt Alley is unusual among Manhattan alleyways in that it runs for three blocks. You can occasionally find some that run two blocks — like Staple and Collister Streets on the west side of Tribeca — but three is a surfeit. The alley goes all the way back to 1817, when local landowners John Jay, Peter Jay Munro, and Gurdon S. Mumford laid out the narrow lane through properties between Broadway and what would be Elm Street (which is now a part of Lafayette) and White and Canal Streets. If this 1830 map accurately reflects the reality back then, the alley might well have run along the stream leading into Collect Pond, which was soon to be placed in a canal today’s Canal Street runs over. In any case, the original Cortlandt Alley presented a rural aspect much different from the one seen today.

The section between Franklin and White was laid out in the 1820s and lies 25 feet farther west than the original section. It was named for a Dutch nabob, Jacobus Van Cortlandt, one of the original European landowners in these parts; the alley, Cortlandt Street, Jacobus Place in Marble Hill, and all the Van Cortlandts this and that in the Bronx, including the mansion and the park, all spring from that family. The mercantile structures we find lining it go back to after the Civil War, when Lower Manhattan’s trade really picked up.

There are other alleys in the immediate area, like Franklin Place (above) and Catherine Lane. There’s one rule about NYC alleys, though. They almost always attract protective sidewalk scaffolding when work is being done on adjoining buildings. Catherine Lane, in particular, has had scaffolding since I began writing Forgotten NY in 1998, and I’ll bet this one on Franklin Place is there to stay a long time.

Before entering Cortlandt Alley proper from Franklin Street I’ll mention 366 Broadway, the Braodway-Franklin or Broadway Textile Building, the rear of which faces the alley. In fact, though Cortlandt Alley has its own house numbers beginning with #2, no real estate is built on it — only the rear ends of buildings on Broadway and Lafayette.

366 Broadway is a lively building that went up in 1907, ringed with female ornamental heads, some snakes here and there, and an Egyptianesque design. It is built near where an old reservoir “collected” water from Collect Pond. If there weren’t so much scaffolding you could see some ancient business advertising etched onto the windows.

Cortlandt Alley forms the eastern boundary of the Tribeca East Historic District, designated in 1992.

Just past Franklin, in what was once a freight elevator in a paper warehouse fronting on Broadway, is the city’s smallest and likely most unusual museum, called simply Museum. Much like Brooklyn’s City Reliquary, its mission is to display found objects and unusual collections, doing so in a cozy, welcoming, well-lit space. The museum’s curators say the exhbits will constantly be changing throughout its operation, but in October 2012, the exhbits included mislabeled food containers collected by sous-chef Lulu Kalman, global toothpaste collection of industrial designer Tucker Viermeister, Polaroid photos discovered by artist Andy Spade, lost objects found on the bottom of the Pacific by deep-sea diver Mark Cunningham, and more. There are also two video screens playing works by filmmakers Richard Sandler and by NYC documentarian Joey Boots.

Other eclectic objects from around the globe, found by submitters, include Russian watches, matchboxes, paperweights, nameplates from the UN General Assembly, magazines, food labels, a cap worn by someone pretending to be a surgeon in a hospital and witnessing an operation, business cards, and an assortment of weird hammers and saws.

Admission is by appointment — it was open as part of Open House New York when I came by. More information: MMuseumm.com.

Cortlandt Alley facing White Street.

Cortlandt Alley facing Franklin. This is the only lamppost installed along the alley.

#80 White Street, NE corner Cortlandt Alley was built in 1868 and originally was tenanted by a carpet dealer.

#77 White, on the SE corner of Cortlandt Alley, was built in 1888 for real estate developer John Dodd. Its more recent claim to fame was the presence of rock venue The Mudd Club between 1978 and 1983. Georgia band the B-52s made their NYC debut here, and it is memorialized in the lyrics of the Talking Heads classic “Life During Wartime.” (and also by The Ramones, Nina Hagen, and Frank Zappa, who viewed the NYC scene with bemusement). The club was named for Dr. Samuel Mudd, who treated John Wilkes Booth, who had injured himself while escaping Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC, where he had assassinated Abraham Lincoln. The long stick he used to set Booth’s broken leg bone came to be called “Mudd’s Club.” News anchor Roger Mudd was a descendant of the doctor.

The Mudd Club was frequented by many of Manhattan’s up-and-coming cult celebrities. Individuals associated with the venue included musicians Lou Reed, Johnny Thunders, David Byrne, Debbie Harry, Arto Lindsay, John Lurie, Nico with Jim Tisdall, Lydia Lunch, X, The Cramps and The Bongos; artists Jean-Michel Basquiat and his then girlfriend Madonna and (later) Keith Haring; performers Klaus Nomi and John Sex; Designers Betsey Johnson, Maripol, and Marisol; underground filmmaker Amos Poe; Vincent Gallo, Kathy Acker, and Glenn O’Brien. wikipedia

Cortlandt Alley, facing Walker Street

The “388” marks 388 Broadway.

Rusted loading dock landing.

Many buildings whose back ends face Cortlandt Alley feature metal or iron shutters on heir windows. The shutters were installed to help inhibit the spread of fires.

Even on this back alley, where few would go, there was the need to keep up appearances and columns or pilasters (half columns that aren’t freestanding) decorate some of the buildings.

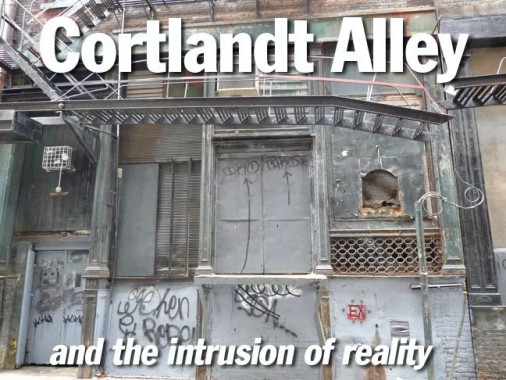

See what I mean about the intrusion of reality? This isn’t a long way from the Apple store on Greene Street but it seems like it.

Cortlandt Alley facing White Street. That light bulb on the right is the only thing illuminating mid-alley at night.

Loading dock at Walker Street.

A battered Cortlandt Alley sign at Walker.

Loft buildings on either side of the alley, north side of Walker Street. 72-76, left, goes back to 1862, while 78-80 on the right was built in 1907 and sits on the former site of the NY & New Haven passenger railroad depot. An earlier buildings contained the offices of the New York Dry Goods Exchange and the Dry Goods Economist, a trade paper.

Cortlandt Alley from Walker Street, facing Canal.

The signs in Chinese denote several sportswear firms fronting on 72-76 Walker.

Half columns, or pilasters, on a building fronting on Broadway. The two on the right have lost their pediments.

Facing Walker Street.

Nearing the north end of Cortlandt Alley.

Canal Street, one of New York’s quintessential avenues, with roaring traffic en route from the Manhattan Bridge to the Holland Tunnel (an underground expressway would come in handy here, but Canal wouldn’t be the same without all that honking traffic) and sidewalk space is at a premium with discount stores in the buildings and sidewalk vendors.

Dr. Thomas Tam (1945-2008) was the co-founder of the co-founder of the Asian American / Asian Research Institute. “The Institute is a university-wide scholarly research and resource center that focuses on policies and issues that affect Asians and Asian Americans.”

10/16/12