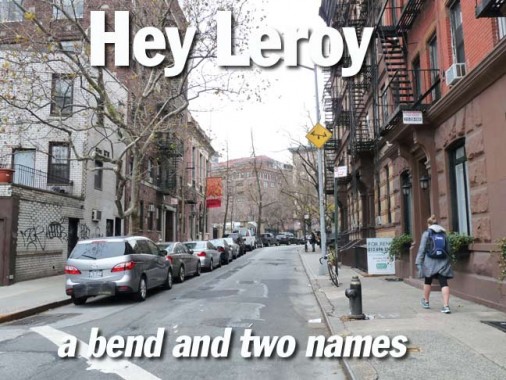

It can be argued that Leroy Street is the most unusual street in all of Manhattan, and perhaps all of New York City.

What other street can claim:

- That it is called by two separate names — and the entire street isn’t known by two names, but only a portion of the street is called a different name.

- The street’s two names occur within the same block, with a bend in the street determining what name is used.

- There are two different house numbering systems, and while one runs east to west, the other runs west to east.

I’ll get into those in some detail later on, but first, here’s a rundown of the street from Hudson east to Bleecker. Overall, Leroy Street’s numbering begins at Bleecker and runs west to the Hudson River, but there’s an exception.

Leroy, spelled Le Roy on older maps, is two blocks north of King Street, and both mean the same thing — though King Street was named for Rufus King, a statesman and abolitionist in the Revolutionary era whose mansion in Jamaica is now a museum, while Le Roy honors Alderman (today’s City Councilman) Jacob Le Roy, an early area shipping merchant who ran a blockade against the British in the War of 1812.

421 Hudson Street at Bleecker is an Italian palazzo-style warehouse built in the late 19th Century or 1911, depending on your source (it didn’t make the AIA Guide to New York City) and it probably was home to printing plants at some time in the past: I worked briefly at a publishing house on Greenwich Street in the mid-1990s, paginating books using QuarkXPress. It was converted to apartments in 1979 (Tiger Woods purportedly is a former tenant) and is condo-izing under its new name, Printing House West Village, to open in 2013.

Between Hudson and West Streets, Leroy isn’t something to write home to Mother about, unless you’re a Belgian block pavement fan. I wonder if someone in town has ever surveyed and notated Manhattan’s (and the other 4 boroughs’) remaining Belgian brick pavements. Perhaps I should consult friends who have walked every block in Manhattan. Yes, I know more than one.

Diagonally across the street from 421 Hudson is 420, which is also #1 St. Lukes Place (not Leroy Street — I will explain presently).

This handsome 4-story red brick building has 3 floors of apartments and business on street level; it is the former home of sculptor Theodore Roszak, whose industrial style, epitomized in his Sentinel near Bellevue Hospital, isn’t my cup of tea, but has many adherents.

In a Forgotten NY vein, what’s interesting about the building is its chiseled corner street signs, which unique among the ones I’ve found, helpfully list the building’s numbers along with the street names.

In 1845, Burton was connected to Leroy by extending it through the cemetery, and the connector street was named St. Luke’s Place after the nearby St. Luke-in-the-Fields Church. Imagine in the above map a street running through the cemetery continuing on an angle from the stump of Burton Street. The Burton name fell out of favor, and was thenceforth part of Leroy. However, the St, Luke’s Place name stuck along the section of Leroy Street that faced the old cemetery (as shown in this 1892 map).

Though the cemetery inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write several macabre tales when he lived in the area in the 1830s, it was closed by 1898 and turned into Hudson Park, a high-concept collection of lush marble terraces and gazebos built by renowned architects Carrere and Hastings. Many of those interred in the cemetery were moved to other burial grounds between the 1850s and 1900, such as uptown Trinity Cemetery at Broadway and West 155th. Some, however — as many as ten thousand — simply remained in place, their tombstones and markers uprooted or plowed under by the City. The Carrere/Hastings vision lasted only 8 years and was then replaced by a more mundane city park.

Today no trace remains of the lush landscaping, as Hudson Park in 1947 was renamed James J. Walker Park after the 1920s NYC mayor “Beau James” or “Jimmy.” Today the park consists mostly of ballfields and also a swimming pool (seen in the film Raging Bull).

In 1914 Walker was elected to the State Senate with the endorsement of Tammany Hall. As Senator, he lobbied successfully for the legalization of Sunday baseball and professional boxing, while continuing to work as a lawyer. Jimmy Walker—also known as “Beau James”—socialized with stars of the Broadway stage and the sports world and became known for his stylish dress. In 1925 he ran a victorious campaign for mayor, again with the endorsement of Tammany Hall. During his first term, he founded the Department of Hospitals, preserved the nickel subway fare, and rooted out corruption in the Police Department and Department of Health.

Shortly after Walker won a second term in 1929, an investigation led by Samuel Seabury was launched to determine if he had accepted bribes for municipal contracts; his relationship with the actress Betty Compton also caused a sensation. Resigning in 1932, after formal charges of corruption had been filed, Walker left for Europe, divorcing his wife and marrying Compton. Returning to New York in 1935, the couple adopted two children; they divorced six years later. In 1940 Mayor Fiorello D. LaGuardia appointed Walker labor arbitrator for the garment industry, and Jimmy became a popular speaker at banquets and rallies. James J. Walker died on November 18, 1946… NYC Parks

The only remnant of the cemetery visible to the eye is this firemen’s memorial, set in place in 1834, honoring Engine Co. 13 firemen Eugene Underhill and Frederick J. Ward, who were 20 and 22 years old, respectively. They perished fighting a blaze in Pearl Street, crushed to death under a falling wall. When the plot became a park the memorial was moved to the St. Luke’s Place side.

As reported by The New York Times, “In this amusement resort, which presents a scene of revelry and gayety every afternoon, stands the only survivor of the days when the park was used as the cemetery for the doomed St. John’s Chapel…The changed conditions of the place are well expressed by this inscription on a brass tablet placed there in 1898: The City of New York devotes to the service and comfort of the living this ground formerly used by Trinity Parish as a burial place for the dead, whose names, although not inscribed, are hereby reverently commemorated.” Daytonian in Manhattan, which has photos of both the cemetery and the park that replaced it.

James J. Walker Park is so named because Mayor Walker lived here, at #6 St. Luke’s Place, during the years he was in office. His father had purchased it in 1891, in a row of handsome row houses that were constructed in the 1850s, shortly after St. Luke’s was extended through the cemetery. Three buildings on St. Luke’s have twin lamps decorating the entrance gate, but these are in place to honor the former home of a mayor –it’s considered something of a tradition. Mayor James Harper’s house on Gramercy Park West also has the lamps.

From the looks of things the building appears to be between owners, as it is somewhat shabby and dilapidated.

Another pair of lamps, at the better-kept #9 St. Luke’s Place. As previously mentioned, St. Luke’s Place buildings are numbered 1 to 17 and both even and odd numbers are in a row running west to east on the north side of the street. At the midblock bend in the road, Leroy Street resumes, and the house numbers begin running east to west, with the odd numbers on the north side and the even numbers on the south side.

Another pair of lamps, at the scaffolded #10 St. Luke’s. This house served as exterior shots for the Huxtable family’s house in the long-running Cosby Show in the 1980s and 1990s.

Many houses still have original railings, or at least very old ones. This one has a boot scraper to get the mud off shoes in the days before sidewalks or welcome mats. The leaves are from the pungent ginkgo, which lines the block.

North side of St. Luke’s Place, with #10 at the far left. The block has been home to editor Max Eastman, author Sherwood Anderson and Theodore Dreiser, writer-director Arthur Laurents (Gypsy) and poet Marianne Moore. #4 St. Luke’s Place was the home of the blind and terrorized Audrey Hepburn character in Wait Until Dark.

#12 1/2 was the home of civil rights attorney Leonard Boudin, and his daughter, Weather Underground terrorist and later public health expert Kathy Boudin.

#17 St. Luke’s is the highest numbered St.Luke’s address. East of here it’s Leroy Street again.

Ceramic ornamentation in the Walker Park playground by artist Lillian K. Rosenberg, installed in 1974.

Keith Haring mural, Carmine Street Pool at the Tony Dapolito Recreation Center, facing Leroy Street. The late great muralist (1958-1990) painted this 18 by 170-foot wall with mermaids and sea-things in 1987. I was able to get onto the roof of the recreation center while giving a chat here just after the release of the ForgottenBook in 2006.

Hudson Park Branch, New York Public Library, 66 Leroy, honors the former name of Walker Park. It was built in 1906.

#51 Leroy Street at 7th Avenue South. Most of the jagged edges from the extension of 7th Avenue south from Mulry Square at Greenwich Avenue to Varick, Clarkson and Carmine Streets after 1912 have been smoothed over — it was run along the cut for the new IRT subway that year. Beginning in 1928, 6th Avenue was extended south in a similar manner.

Village Tavern at Bedford and Leroy is coincidentally as old as Forgotten New York.

18 and 20 Leroy, between Bedford and Bleecker. These buildings go back to the 1840s.

The dormered #11 Leroy, with adjoining #13, are about as old.

Leroy ends its northeast progress at Bleecker. Though they do not show much signs of age, these 4-story buildings go back to the 1830s.

12/2/12