While meandering aimlessly in upper Manhattan in February 2013 I came upon a single intersection, Broadway and Isham Street, where there are several leftover relicts from several different ages that still survive.

Before getting into those, I’d like to dispute the pronunciation of the name Isham, which, I’m told, is EYE-sham. This is plainly ridiculous. Since this is a one-syllable word, it should sensibly be pronounced the way the “i” is pronounced in the word is or it, which is always the way I did it until told differently. Then again, I think Corelyou should be pronounced KOR-tel-yew and Houston should be pronounced the same as the city in Texas.

The Isham family, who lived in northern Manhattan in the 19th Century, donated some of their land to the City in 1912, which was made into the park, and a street that was later built here also got the Isham name.

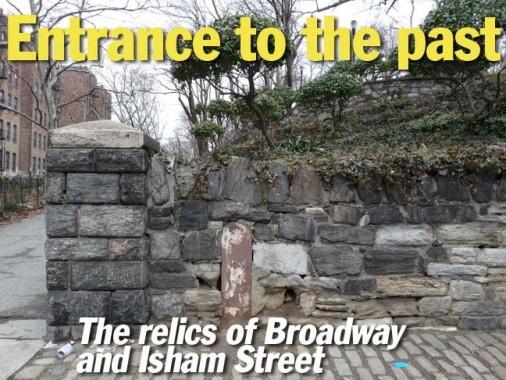

If you exit the 207th Street station, the end of the line of the A train, at the northern end, you’ll be on Broadway a bit north of Isham Street. From there, walk a short way up Broadway to the entrance of Isham Park, one of three large parks in upper Manhattan along the Hudson River. You will see a retaining wall made of boulders where the southern entrance to the park leads west. There is a door-like object in brownstone right next to the entrance. It’s not a door — it’s the 12-mile marker of the Post Road to Boston (and Albany — the roads split in the Bronx), which, at one time, was the only road in these parts.

The 12 mile marker with original notations (myinwood)

“In the days of our earlier outings about Inwood there stood by the roadway two of the ancient milestones; these were the 12th and the 13th indicating the distance from “N York.” The 13th milestone which stood on the west side of the Kingsbridge Road near the extreme north end of the island has disappeared, but the 12th milestone still remains- built into the retaining wall at the Isham Park entrance. We were told that the stone originally stood at the 203rd Street corner; the present pitted appearance of the stone is attributable to a shotgun charge fired by a hunter who wished to empty his piece on the return from a hunt.” Inwood historian William Calver, in myinwood

The Post Road, which followed an already established Native American trail, was established in 1673 as couriers bringing mail to different locales in the colonies traveled the trail, which was then very rough and interrupted in several locations. Couriers would mark miles by hacking cuts into trees at intervals. After nearly a century, the road was straightened and improved somewhat between New York and Boston, and from 1753-1769 heavy stone markers were set at one-mile intervals, with the surveying supervised by Benjamin Franklin. Postal rates were set by the distances between one spot and the other. Did “Poor Richard” handle this 12-mile marker? Perhaps he did.

Marker #12 was originally placed on the Post Road (later Kingsbridge Road and later, Broadway) and where 190th Street is now, but when distances were recalibrated with 0 at City Hall, the stone was moved to about 203rd Street, where it was later abandoned. At some point in the early 20th Century, it was placed in the Isham Park wall. Over the years the writing on the stone has weathered off, or was chiseled off by vandals.

Other mile markers are still extant: #10 is at the New-York Historical Society…

…and #11, with its lettering worn off as well, is in Roger Morris Park at the Morris-Jumel Mansion at Edgecombe Avenue and West 160th Street.

The old Post Road itself survives in the paths of the Bowery and 4th Avenue downtown, Broadway uptown, and in Van Cortlandt Avenue and Bussing Avenue in the Bronx. (Bronx’ Boston Road was built as a connector road to the Post Road in the 19th Century.) The old Post Road route is also followed along parts of US 1 into New england.

I’ve covered it before, but here’s a relatively newer relic from the 19th Century: a surviving gaslamp post at Broadway and West 211th, directly across Broadway from the mile marker. It is the sole survivor of NYC’s public street gaslamps except for another one in Patchin Place in the Village, and every time I see it I marvel that a truck hasn’t plowed into it and it’s still there.

The Isham Park entrance features a row of Type A park lamps, which are rarer than their Type B cousins. The main difference between A and B is that the A shafts are taller.

Like other parks in northern Manhattan, the site of Isham Park played a crucial role in the battle of Fort Washington during the American Revolution. The site served as a landing point for Hessian troops coming up the Harlem River to drive the American forces to Westchester and New Jersey.

In 1864 William B. Isham, a wealthy leather merchant, purchased twenty-four acres along the Kingsbridge Road, now known as Broadway, from 211th Street to 214th Street, and northwest to Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

The park originally included the old Isham mansion, stables, and green house, with the mansion located at the summit of the hill. Julia Isham Taylor donated a six-acre parcel of her estate to the city in remembrance of her father in 1912. She wanted the estate’s views of the Hudson and Harlem Rivers, the Harlem River Ship Canal, and Spuyten Duyvil to be preserved for future generations to enjoy. Julia’s daughter, Flora, donated her portion of the estate to the city in 1916. With Parks Department purchases in 1925 and 1927, the land for Isham Park was assembled. These acquisitions explain the unusual shape of the park which juts into Inwood Hill Park so that the two share a boundary in the middle of a field.

The mansion, stables and greenhouse proved too costly for the Parks Department to maintain and they were demolished in 1940.

Good Shepherd Church celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2012. The first church was a wood frame building that was moved across Cooper Street around 1930 and later razed to make way for an addition to the elementary school. When the IND subway reached Inwood in the early 1930s, the population increased, necessitating a bigger church, and the present Romanesque church was built in 1935 from Fordham gneiss mined in Manhattan and Bronx quarries.

On the Isham Street side of the church is an iron cross that was salvaged from the ruins of the World Trade Center after it was destroyed by terrorists 9/11/01. It was installed as a memorial garden at Good Shepherd Church on June 7, 2002.

Looking east on Isham Street you see the dome of the Gould Memorial Library, constructed in 1899 (Stanford White, architect) on the campus of what was New York University but is now Bronx Community College. Zooming in tight with the camera…

… you can see the colonnades of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, where you will find busts of 98 of the country’s greatest politicans, scholars, teachers and authors, created by some of the country’s most noted sculptors. Even the name plates under the busts were made by Tiffany Studios.

Most of the names familiar from American history books can be found in the Hall, including Abraham Lincoln, Alexander Graham Bell, Samuel Morse, Robert Fulton; both Wright brothers and Thomas Edison are represented. There are several lesser-known figures such as astronomers Simon Newcomb and Maria Mitchell, first American Nobel Prize winner in science Albert Michelson, and anaesthetist William T. Green Morton.

At Broadway and Isham, on the same corner of Good Shepherd Church, is a 1910-1915 era FDNY alarm. It still has the shaft that held the fire alarm light, originally covered with clear red glass, later an orange plastic sphere.

Finally, in the 207th Street station itself is an old-fashioned track indicator that still gets the job done. It’s likely several decades old.

2/28/13