Though I have been writing Forgotten New York for a long time — I started in 1998 — there are still adventures I haven’t yet considered, such as a simple walk down Flatbush Avenue from the Manhattan Bridge all the way across the Marine Parkway Bridge to the Rockaways. That’s a multiple-day project. For me it’s still a one-day on a bike, and while I have never done the whole route, I’ve certainly cycled major parts of Flatbush Avenue, which is a mostly diagonal route through the heart of Brooklyn. It was originally a colonial-era trail called Old Flatbush Road, possibly evolved from a Native American trail. It was later beset with tollbooths and became a pike, or tolled road, but by 1900 it had become plain old Flatbush Avenue. The name is Dutch and is only semi-literal, a British transliteration of v’lacke bos, or “flat woodland.” So, for those who think “Flatbush” describes flat bushes, you’re half right.

WAYFARING MAP: Downtown to Prospect Park

At the beginning of this article, at least, I’ll have to tread on well-worn Forgotten NY ground, but I’ll try and add some extra bits and pieces. This is Willoughby Street at Albee Square/Gold Street. Willoughby parallels the Fulton Mall and till recently, plenty of Blimpies, fried chicken joints and bail bonds salesmen could be found along its length, but with the rest of downtown Brooklyn, it seems to be rapidly upscaling.

The center building, which looks like one of the monoliths from 2001: A Space Odyssey clad in one of the masks Rorschach wore in Watchmen, is the 38-story Toren residential tower. A closer look will reveal thousands of visible rivets. It was opened in 2009 and condos there can sell for over $1 million.

Looking north on Flatbush Avenue Extension at Willoughby. 4 Metrotech Center, left, was built in the 1980s and harmonizes with the nearby 1931 Art Deco Bell Telephone building. The Toren dominates the right side.

Flatbush Avenue Extension was created in concert with the Manhattan Bridge, which opened in 1909, to bring traffic onto Flatbush Avenue. It still awkwardly has to be called an “extension” because Flatbush Avenue addresses begin at #1 on Fulton Street. In Williamsburg, a similar situation existed when the Williamsburg Bridge was built and Grand Street was given a spur leading to it. For many years it was called “Grand Street Extension” but in the 1970s, in a nod to the Puerto Rican population in the neighborhood, it was changed to Borinquen Place.

As we’ll see, Willoughby Street was one of the few streets in this area to be left intact during the mid-20th Century spate of “urban renewal” which mostly meant ripping down old tenements and installing Corbusier-esque “towers in a park.” The 3-story walkup on Willoughby and Fleet Place is a rare neighborhood survivor.

Fleet Street is a rare diagonal against the grid, or had been, before much of it was eliminated to make way for the University Heights Towers, seen at right.

The ghost of Fleet Street can be seen in the angle of the striped section of the roadbed. Fleet Street used to continue northeast, while Fleet Place, which is mostly still intact, went north.

The Department of Transportation still dutifully marks the difference.

Here’s a 1929 Belcher Hyde atlas plate of the area we’re in. Very few of these streets have been left as they were. To my original point, note how Fleet Street and Fleet Place diverge just south of Willoughby, and today, only the very small piece of Fleet Street between Flatbush Avenue Extension and Willoughby exists today.

–Oddly, tiny Fair Street is still there, though now Fleet Place ends there.

–Also, oddly, the title “Albee Square” which honors the long-gone Albee Square Theatrer at DeKalb and Fulton, was also applied to Gold and Prince Streets.

–Bolivar Street is now covered by the University Towers Houses, and Lafayette Street by Long Island University. Hudson Avenue, once a busy north-south vertical that even was home to an elevated train at one point, has been totally eliminated except for short stretches in Vinegar Hill and a one-block remnant between DeKalb and Fulton. I’ll deal with Debevoise Place in a bit. Note the huge plot housing the Paramount Theatre on Flatbush and DeKalb.

The map of the same area looks like this in 2013. In the mid-20th Century there was an absolute mania to clear up and simplify complicated street layouts, in part to make them easier for automobiles to navigate, and also in part because large plots of land were needed for housing projects and expanding businesses like Long Island University.

The former intersection of Willoughby Street and Hudson Avenue is marked by Brooklyn’s last “humpback” street sign. Hudson Avenue, the cross street, can be seen faintly in the “hump.” Somehow, this sign has missed the attentions of the DOT, which relentlessly takes down old signs (except, of course, for the sun-bleached ones that really do need replacing).

In 2013, a new program sponsored by the city and by Citigroup, the banking behemoth, allowed New Yorkers to rent branded blue bicycles for various pre-set intervals, paying with debit or credit cards. When time was up on your rental, you had to return the bike to the rack and re-rent, if so desired, or you could rent for an entire day. This Citibike terminal is at the former corner of Willoughby Street and Debevoise Place.

If you look at the Belcher Hyde atlas, you see a street called Debevoise Place running from Flatbush and DeKalb north to where the two Fleets meet. Though Long Island University took over the street decades ago, at first it kep the street open to traffic, calling it University Place. In the 1980s it was closed to traffic and turned into a pedestrian walkway.

In the photo here, at left is the old Debevoise Place and at the right is a still-extant part of Fleet Street, both seen from Willoughby. The Debevoise family owned land here in the colonial era, and one of the adopted daughters of John Debevoise, Sarah, attracted so many gentleman callers that the driveway at their manse became known as Love Lane in Brooklyn Heights, so the story goes.

Looking north at the Long Island University entrance on Flatbush Avenue Extension. We’ll see a couple of buildings along the way in the Brutalist tradition, a very severe style championed by architect Paul Rudolph, among others. One of the hallmarks of Brutalism is that it looks like you could get a severe cut just by staring at the corners long enough.

In this case, the Schwartz College of Pharmacy/Humanities Building actually took an older building and gave it a Brutalist cast in 1967. Alongside it is the steel campus entrance arch, built in 1985.

This is a front view of the arch — in the background is the 1928 Metcalf Hall (see below), originally the Paramount Theatre, built in 1928.

For decades this was a clock and thermometer sponsored by Dime Savings Bank, which still stands in domed glory at DeKalb and Fulton Streets at Albee Square. I saw it working just recently but it was only giving the temperature in Celsius. During my 4 years in high school, I took two buses and transferred at 4th and Atlantic Avenues, and always checked this for the temperature — I had to know. It’s still mounted on the west side of Flatbush Avenue Extension.

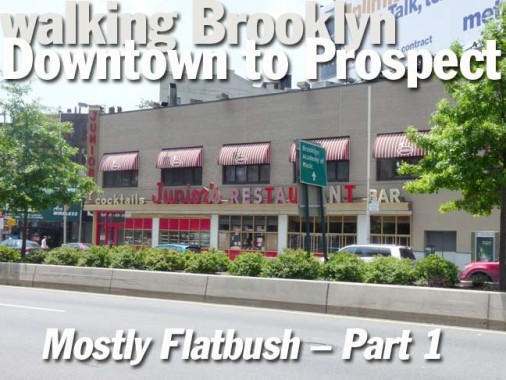

Junior’s Restaurant, so named because it was originally run by the sons of founder Harry Rosen, Marvin and Walter. Though its website and other reference volumes say it was founded in 1950, Rosen had run a diner here since 1929 at DeKalb and FAE. Perhaps 1950 was the year the name was changed.

Though Junior’s cheesecakes are as well-regarded and well-remembered as Ebinger’s baked goods, I have to admit I’ve never had one, though my family and I were frequent Junior’s customers when we shopped at nearby A&S on Fulton Street in the swinging Sixties. I’d marvel at the generous portions of coleslaw and pickles, the big burgers and, most of all, the incredibly huge onion rings. They were like onion fritters, they were so large. I imagine they’re still prepared the same way. I haven’t been in Junior’s since the 1970s, but that’s more coincidence than anything else, and I look forward to visiting again some day.

Catercorner across DeKalb Avenue, Junior’s faces off against Applebee’s, sort of the McDonalds of brewpubs/diner combos.

The Brooklyn Paramount Theatre was an entertainment hub, 4000-seat vaudeville theatre and movie palace from its construction in 1928 until 1960, when it was purchased by Long Island University. LIU has retained many of the theater’s interiors on its basketball court, including a massive Wurlitzer organ. The LIU Blackbirds played here until 2006.

The Paramount was host to early jazz shows, introducing Duke Ellington to Brooklyn audiences in 1931, as well as Yiddish kletzmer. Rock and roll/R&B package shows run by disk jockey/entrepreneur “Mr. Rock and Roll” Alan Freed were frequently booked from 1954-1959, and even after Freed fell from grace in a payola scandal (in which he accepted payments to plug different acts), Clay Cole presented the shows for a few years after that.

Con Edison (New York’s energy provider) headquarters at Nevins Street and Flatbush Avenue and Fulton Street, or the Ministry of Love as I call it (where Winston Smith was tortured to “get his mind right” in George Orwell’s “1984“) …

After The Fox

In the 1970s Con Ed tore down the Fox Theatre Building, a tall skyscraper with the theatre on its ground floor.

In 1926 Fox interests acquired control of the triangular property bounded by Flatbush Avenue, Nevins Street, and Livingston Street in Brooklyn. In 1927 the site, partially occupied by the Cowperthwait Building, was cleared. The cornerstone of the Fox Theatre was laid on September 27, 1927 at the junction of Flatbush Avenue and Nevins Street in the presence of numerous civic dignitaries, prominent members of the business community, and theatre representatives, Borough President James A. Byrne officiating. William Fox himself was not present, but what was said to be the first check he ever earned was enclosed in the stone along with the day’s Brooklyn newspapers. Historic Structures, where amazing views of the ornate interior can be seen.

Such was the theater’s importance that from 1928-1971 the intersection of Fulton and Flatbush was called Fox Square.

The 4,088-seat house was designed by C. Howard Crane and incorporated elements of several architectural styles–Gothic, Spanish Baroque, Byzantine, Near Eastern, and Art Deco… Streets You Crossed, which has many more interior shots, including Fox’ own Wurlitzer.

Perhaps the Fox’ main contribution to pop culture and why it’ s still remembered now are the rock and roll package shows presented there by WINS disk jockey/compere Murray Kaufman (“Murray the K”) who, when the Beatles arrived in the USA in 1964, affixed himself to their orbit so tightly that he became known as The Fifth Beatle. Before all that, though, Alan Freed staged rock and R&B revues at the Fox; but after the payola business, Kaufman took over for him, both on WINS and as host for the shows.

For several years, Murray the K’s rock and R&B shows held forth at the Fox, presenting Top 40 acts like Johnny Mathis, Bobby Vee, Dion, Joey Dee & The Starliters, Gary U.S. Bonds, Bobby Lewis, Timi Yuro, the Isley Brothers, Jan & Dean, the Orlons, Dee Dee Sharp, the Coasters, the Vibrations, the Dovells, the Harptones, the Ronettes, Steve Alaimo, Chuck Jackson, Little Peggy March, The Four Tops, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Patti Labelle & the Bluebelles, the Wildtones, the Beau Brummels, Martha & the Vandellas, the Temptations, and the much longer list goes on. Kaufman also presented Manhattan shows that turned out to be the United States debuts of The Who and (The) Cream.

29 Flatbush has joined a number of residential towers built the past few years that attempt to challenge the primacy of the 1929 Williamsburg Bank Tower further down the street. It’s a futile enterprise.

Always on Nevins:

While the banded-masonry building with the large arched entrance at the SE corner of Flatbush and Nevins Street is impressive as is, albeit giving an aura of faded glory, it was once a great deal more showy — the tower, now cut back to just 7 stories, was once 17 stories/225 feet tall and boasted a clock tower! It was built in 1893 by men’s clothier Smith, Gray and Co. to replace an earlier 1888 clock tower that had fallen onto the Fulton Street el.

Smith, Gray went bankrupt in 1914 and the building has been home to mixed uses ever since then; pawnshops, pool halls and cafeterias have occupied the first and second floors. The clock tower was demolished in the 1940s and the building was cut back to its present 7-story height, and the shortened tower is now nearly vacant. The NY Times’ Christopher Gray: “It is, like the Roman Colosseum in Lord Byron’s play Manfred, ‘a noble wreck in ruinous perfection.’ ” A cast-iron Smith, Gray building on Brooklyn’s Broadway in Williamsburg has been landmarked but not this one.

Above from FNY’s Boerum Hill page.

A short detour on Fulton Street to the Brooklyn Academy of Music Harvey Theater at Rockwell Place, which has maintained its Ionic-columned exterior from when it was the Majestic:

The Majestic Theatre was a 1,708-seat legitimate theatre, later vaudeville house, built in 1904 on Fulton Street near the Orpheum Theatre and adjacent to the Strand Theatre in downtown Brooklyn. Recall the theatre playing triple features in the mid-1950’s similar to the programming at the Savoy Theatre in Jamaica, Queens.

The Majestic Theatre closed around 1968 and sat dormant until 1987, when it was rescued by the nearby Brooklyn Academy of Music and ‘renovated’ in a distressed state. It was then known as the BAM Majestic Theater for a number of years and was used for live performances, and later was known as the BAM Harvey Theater, with a seating capacity of 874.

In June 2013, the Harvey Theatre premiered its new Steinberg screen, for classic and independent movies on a 35 foot x 19 foot screen, with digital projection and 7.1 Dolby Digital sound with 42 surround speakers. cinematreasures

The plot formed by the triangular intersection formed by Fulton and Flatbush is oddly empty, so a local commenter has written some aphorisms on the pavement.

Flatbush Avenue between Fulton and 3rd Avenue has an unfinished or deserted quality; the development surrounding the Atlantic Yards complex kicks in at 4th Avenue, and in between is dominated by the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Pioneer Warehouses, meanwhile, seemingly bides its time until it takes its turn as a large condo redevelopment. Not saying it’s happening — but it seems like a candidate to me.

Christopher Gray cited the Pioneer in the NYTimes in 1988:

Established in 1896, the Pioneer Warehouse Company was an outgrowth of a family auction business initiated on Fulton Street 16 years earlier by Samuel Firuski. Choosing the name Pioneer to reflect what he perceived to be his position in the industry, Firuski acquired a parcel for his warehouse on a triangular block bounded by Flatbush Avenue, Rockwell Place and Fulton Street.

It was a strategic location. The elevated ran down Flatbush Avenue and the Long Island Rail Road was moving to build a new terminal a block south at Flatbush and Fourth Avenue.

There are also four ship’s prows sticking out of the wall just before the roofline.

Sticking up out of nowhere, the Williamsburg Bank Tower, 45 stories in height, has never had to compete with a thicket of surrounding skyscrapers and has always been dominant. Those days may be ending, though, as taller area buildings have been built to challenge its supremacy. The detailed lobby and former commercial banking area is a must-see, and can be seen in the winter when the “Brooklyn Flea” takes over the space.

There’s also a former observation deck, complete with historic signage about the Battle of Brooklyn in Revolutionary days, but it’s been closed for many years and the building, known for the many dentists’ offices that gave it the nickname “The House of Pain,” have been joined by privately owned condos. The official title is now “One Hanson Place.”

The lampposts along this stretch are called “8th Avenue posts” since they first appeared on that Manhattan avenue around 1990.

Temple Square, 3rd Avenue, Flatbush Avenue, Lafayette Avenue and Schermerhorn Street. This is a somewhat rundown section of Flatbush Avenue that hasn’t seen the ongoing revitalization that, say, Flatbush and 4th Avenues have.

3rd Avenue becomes Lafayette Avenue at Flatbush and Schermerhorn (inexplicably pronounced by Brooklynites as “SKIM-merhorn”), and looking west, it’s dominated by the dignified yet somewhat rundown Baptist Temple.

The present Baptist Temple sanctuary (1918) has been host to many famous preachers, and contains windows made by Colonial Art Glass of Brooklyn from sketches by Corwyn Knapp Linson. Edward Morris Bowman, a founder of the American Guild of Organists, established the largest volunteer choir in turn-of-the century America, of which Alexandre Guilmant was an honorary member.

On the evening of July 7, 2010, a devastating three-alarm fire caused serious damage to the church interior and organ. NYC American Guild of Organists

Brownstoner’s Montrose Morris, by now one of Brooklyn’s foremost architectural writers, has the whole story as well as some interesting interior photos.

3rd Avenue’s oldest

The former PS 15 and later NYC Board of Education Certificating Unit and the Williamsburg Bank tower thrust competing fingers at the sky. This is likely the oldest building on 3rd Avenue (and State Street), having been built in 1840. It was given a red paint job a couple of decades ago that has long since faded to pink. It’s certainly time someone revitalized this venerable campaigner. In 1974 your webmaster got working papers here so I could work while still under 18 years old. I remember getting a physical exam by a bored doctor in a dark room.

You have to like the way “Public School No. 15″ is etched above the second story arched window. It’s as if someone did it with their finger while the concrete was still wet. That might be what happened. A more advanced rendering is chiseled on the Schermerhorn Street side.

Today the building hosts a branch of the occasionally controversial Khalil Gibran International Academy, as well as the Metropolitan Corporate Academy High School.

Before about 1880, 3rd Avenue from Flatbush Avenue to about Carroll Street was called Powers Street. It likely was changed to 3rd Avenue because there was another Powers Street in East Williamsburg (Brooklyn annexed the city of Williamsburg in 1855). This is the only remnant of 3rd Avenue’s Powers Street days.

Young Women’s Christian Association, 3rd and Atlantic Avenues. The YWCA was founded in 1888 and this 7-story branch was built here in 1927.

Women of all stripes have walked these echoing hallways: Alvin Ailey dancers, electrical engineers, former prisoners, retired teachers and an actress on the HBO series “The Wire.” About a dozen of the current residents have been here since the 1950s or ’60s, including one woman who came to the Y directly after aging out of foster care. New York Times

#29 3rd Avenue, which has the inscription “Brooklyn Central Dispensary” above the ground floor. Again, Montrose Morris:

The Brooklyn Central Dispensary was a charitable medical organization founded in 1855, in a building on nearby Flatbush and Nevins. The facility provided free treatment and medicines to indigent patients. This new building opened to much fanfare in November of 1890. The Dispensary originally had the clinic on the ground floor, with a waiting room, exam and operating rooms and a pharmacy. The second floor had offices, a dentist’s office, and rest rooms. The third floor housed the pharmacist and his wife, and the top floor, the “janitress”. The Dispensary treated over 14,000 patients in its first year in the space. Only the pharmacist and janitress collected salaries. Today, the building is co-ops.

518 State Street, just east of 3rd Avenue, wears its status as a former stable building. Or, perhaps, the owner just likes horses.

Returning to Flatbush — where it meets Atlantic Avenue at an intersection called Times Plaza because of a Brooklyn newspaper called the Times that vanished many years ago, is probably the most dynamic intersection in Brooklyn, with the most change during a 30-year period. It’s needed just about every year of that 30-year period to manifest the changes, though.

There’s been a Long Island Rail Road station at Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues since the mid-1800s — the station has operated continuously since then. In 1907 a handsome brick terminal building was built here, and this corner became the gateway to Long Beach, Hicksville, Hempstead and other Long Island points. Gradually the city let the terminal decay because in the go-go 1950s and 1960s the LIRR Dashing Dans increasingly turned to the World’s Longest Parking Lot, the Long Island Expressway, for island travel. Besides that, Penn Station, in its glory days from 1910 to 1960, was in midtown Manhattan and was the LIRR terminal of choice.

Finally the brick terminal was torn down in the 1980s, but the station remained an underground venue alongside the IRT subway (rumor has it there used to be a track connection). Finally, in the 2000s with the construction of Bruce Ratner’s Atlantic Terminal Shops, which had ultimately replaced a group of slaughterhouses, the occasion was ripe for a reconstructed terminal, the rather bland building shown here.

For some fascinating views of the insides of the old terminal, Art Huneke is the man to see.

A fascinating relic of that golden age of railroading is the old Heins and LaFarge entrance stationhouse of the IRT Subway, which arrived in 1908. At one point the Long Island Railroad and the IRT Subway traveled underground, while Brooklyn’s 5th Avenue El traveled down Flatbush Avenue here. The el disappeared in 1940.

But the old kiosk has hung on. Beginning in the 1930s various lunch counters sprung up, barnacle-like excretions on the kiosk’s exterior. In the 1980s the last of them were removed, but it then was open to the ravages of graffitists and vandals. Finally in the early 2000s the MTA restored the whole complex, but since the entrance is amid the fast-and-furious intersection, it’s now impractical as a subway entrance. It now works as a skylight.

This marked the first time I had been past Barclays Center, opened in November 2012 (an event delayed by “Superstorm”, or Hurricane, Sandy in October). It is the present home of the Brooklyn Nets, a major concert venue, and the future home of the New York Islanders (who I hope keep the name). It’s the first component of a large residential and retail project developer Bruce Ratner hopes to build on top of the LIRR right-of-way between here and Vanderbilt Avenue; Ratner forced the removal of many businesses and residents, including some historic structures. In this FNY post, I decried the process.

The arena is a done deal now, though, so all that’s left is an assessment of the structure itself from the outside (barring a stubhub purchase, ticket prices are too rich for me). The hole over the front entrance reminds me of the Guardian of Forever from Star Trek turned on its side, and that prematurely rusty look is unfortunate. That’s all I got.

Norman Oder continues to look at the machinations of the ongoing project at Atlantic Yards Report.

Long before Barclays Center was built, the triangle formed by Flatbush, Atlantic and 5th Avenues was dominated by a used-car lot and the Underberg Building, a kitchen supplies distributor. This is a photo from about 2000.

The area around Barclays hasn’t completely shedded its rough and ready aspect, as shown by this building on Flatbush Avenue and Pacific Street.

Bergen Tile, Flatbush and Dean Street, is one of the businesses bought out and then vacated in favor of the future Ratnerville.

NY Chess and Game Shop is on the west side of Flatbush Avenue and therefore safe.

Because Flatbush Avenue is a diagonal through a grid, there are plenty of buildings like this on a triangular plot. This is the former Triangle Sports Shop at Flatbush Avenue, Dean and 5th.

There’s a corresponding “triangle” on the east side of Flatbush Avenue at 6th Avenue and Bergen Street.

The east end of the current Barclays complex at 6th Avenue contains offices associated with the arena. There’s plenty of space for bikes, but I wonder how many of the office jockeys bike to work. 6th Avenue between Pacific and Dean Streets looked quite different until just a few years ago…

…because it was dominated by the old Spaulding factory, that at one time turned out millions of “spaldeens”, rubber balls used by stickball fanatics. In its latter years the building was converted to condominiums.

When I first encountered it in 1999, the factory was still covered in painted signs advertising the sporting goods company.

On Pacific east of 6th, it looks like I have found a Type 2 Volkswagen bug bus, though it’s had the VW nameplates on the chassis and axles stripped off.

Carlton Avenue lost its bridge over the LIRR yards for awhile, but it was recently reconstructed.

End Part 1. In Part 2, I’ll explore some of the Prospect Heights landmarked district, as well as follow Flatbush Ave to Prospect Park.

8/4/13