While its name might sound feminine, Greenwich Village’s Jane Street is not named for a woman (in most cases the wife of a wealthy landowner) like Ann, Hester, or Catharine, further downtown. Instead, the story goes, there was a landowner named Jaynes during the colonial era who would up bequeathing his name to the street.

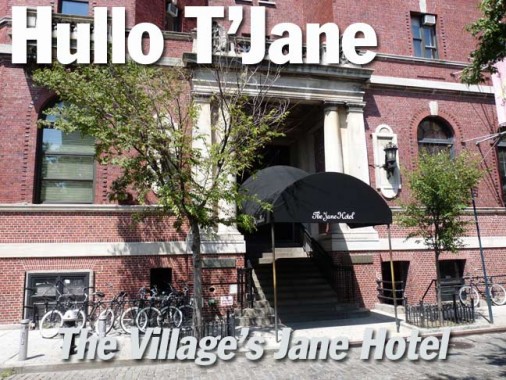

I was staggering up West Street in August, tongue lolling from the unbearably high 85-degree temperature, when I chanced upon a building on Jane Street I had seen only from across West Street before, in forays up Hudson River Park, and even before it was a park, when it was massed with abandoned piers, rotting away in the era after shipping had vacated the water’s edge.

It’s a massive brick building with an octagonal corner that from the air has the seemingly matching proportions to a stop sign. The tower looks out over the Hudson, and was there long before the view was blocked by the West Side Highway from the 1930s through 1970s, and occupants of the rooms there enjoy that vista once again. Balconies and stone escutcheons decorate the third floor, and massive brackets anchor the roofline.

A hint regarding the building’s original purpose can be glimpsed in the massive stone escutcheons, which depict anchors accompanied by life preservers, kelp, a sea-thing resembling the Creature From The Black Lagoon. In 1908, William A. Boring (whose architectural designs weren’t), also the designer of much of Ellis Island’s receiving stations, was behind the drawing boards for what was originally the American Seamen’s Friend Society Institute, meant as visiting sailors’ lodging and as a “temporary refuge” for sailors in distress. The building featured a chapel, concert hall and a bowling alley; a beacon shone to the ships in the Hudson from the top of the tower.

In 1912, the surviving crew from the Titanic were housed here so they would be close to the courts where the inquest regarding the disaster was held. By 1944, the sailors were gone, in a official capacity at least, and the YMCA was running it as an SRO hotel. (Though the 1970s Village People video “YMCA” was filmed on West Street, this wasn’t the YMCA they had in mind; that one was the McBurney on West 23rd.)

During the 1990s and early 2000s the Institute became the Riverview Hotel, catering to the homeless and down-and-outers, but in 2008, the midst of the Bloomberg luxury era, it was purchased by developers Sean MacPherson and Eric Goode and converted into The Jane, and it’s now posher than it was ever meant to be.

There are rooms available in the $100 per night range. But they’re 50 square feet.

“Live Free, Ride Free” is the motto, more associated with Harley-Davidson motorcycles, emblazoned on these bicycles locked outside the Jane Hotel fence. What’s the story here?

More on the Institute and Jane Street

10/17/13

If you’re not sure what the title card phrase means, this should answer the question.