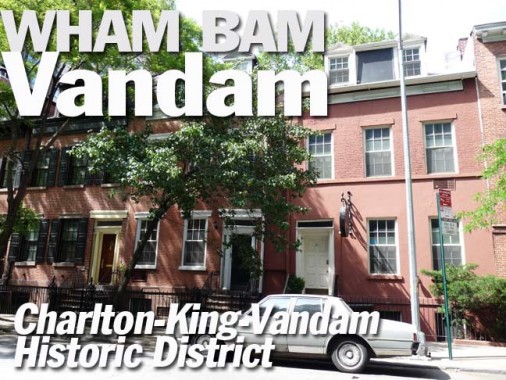

When you are roaring up Sixth Avenue in a cab sometime, divert your attention from your cell phone and take a look at the edge of some very old houses at King Street. They are part of the Charlton-King-Vandam Historic District (between 6th Avenue and Varick Street) and comprise some 72 Federal- and Greek Revival-style houses, many of them built as early as the 1820s. They stand on land known from the late 1700s as Richmond Hill.

The land had passed down from the Dutch era, the late 1600s, from a freed slave called Symon Congo to Trinity Church to British major Abraham Mortimer (who built the mansion that gave Richmond Hill its name). After the revolution, Richmond Hill became the official residence of the Vice-President for just one year when the Capitol was located in NYC. In 1794, Richmond Hill became home to Senator Aaron Burr, later Vice-President and Alexander Hamilton’s killer in their 1804 duel. In 1817, Burr sold the property to fur magnate John Jacob Astor, but the mansion’s days were numbered when Charlton and King Streets were cut through. It was placed on logs and rolled 45 feet away from the street. This bought it some time, and it survived as a tavern, a country resort, and a theater; it was razed in 1849. Meanwhile, Astor saw a profitable real-estate investment at Richmond Hill and built dozens of row houses on Charlton, King, and Vandam Streets, and luckily, most have survived to the present.

Oddly the district, to me, should be called the Vandam-Charlton-King district, matching the running order south to north, but the city chose to follow the alphabet.

Vandam Street

This is always spelled on NYC maps as Vandam, not the Dutch Van Dam, and both Brooklyn and Queens spell their Van Dam Streets with two words. I don’t know if SoHoites say VAN’dam, or the equal emphasis of VAN DAM. The street, according to Henry Moscow’s Street Book, was named for a prosperous merchant, Rip Van Dam, who governed NYC from 1731-1732 despite not knowing a word of English. New York was between British governors at the time. In Sanna Feirstein’s Naming New York, she insists it was named for a liquor dealer, Anthony Van Dam. I don’t know when the space between the Van and Dam was eliminated.

25, 27 and 29 Vandam Street (from right to left) have maintained close to their original appearance since they were built in the 1820s, with pitched roofs, dormers and delicate ironwork.

Ditto, #21, 23, and showing #25 again, all more or less perfectly preserved. Some relics are to be found if you look closely. Name that car in front of #21!

#21 has a large circular sign affixed beside the doorway, apparently wood cast iron, with “21 Renato” chiseled into it. This was a mystery to me until I found a postcard:

Renato’s was a mid-20th Century Italian restaurant operated by Renato Trebbi and established in 1923, and for all my searching, my research is silent on anything further. I wonder if the sign dates back to the restaurant, and if the current owners have kept it around for purely esthetic considerations.

In Comments: the restaurant closed in 1976.

I’m unsure if all the houses in the district one had doors like this, with freestanding Ionic columns guarding the entrance, and a stained glass transom window. In any case the owners of #25 have excellently preserved theirs.

#15 Vandam would be another in the handsome row of 1820s Federal style houses if not for the fact that Tammany Democrats founded the Huron Club here in the late 19th Century as a clubhouse. Prominent clubmen included Dan Finn (whose son, a WWI hero, is honored by Finn Square) and Jimmy Walker, NYC mayor 1925-1932. A theater was founded in the 1920s at #15 Huron and has been known by various names including the Village South and the SoHo Playhouse. Works by playwrights Terrance McNally, Sam Shepard and LeRoi Jones have been produced here. A basement nightclub is called, naturally, the Huron Club.

#13 is another in the Vandam row, but it is adorned with a sea shell and small plaque in the front identifying it as the former residence of artist Marguerite Stix (1908-1967). She founded the Rare Shell Gallery here in 1964.

To Marguerite Stix art and life were inseparable. As a gifted child, a prize-winning student, a concentration camp prisoner, a penniless refugee, a designer of accessories for the haute couture, a factory worker, a recognized sculptor and painter, a creator of widely sought-after jewelry and of fantastic ephemera, she never departed from her deeply felt celebration of life and its meaning. Human sensibility, the wonders of nature, exuberance or despair, humor or play, vulnerability or bravado, infancy or old age, the simple joys of home or the elegance of the privileged world – all called into play her extraordinary talents…

… Although Stix is best known for her work with seashells, the foremost element in her work, whether pictorial or sculptural, is the poignancy of the vulnerable creature, animal or human. The tremulous newborn horses, the troubled women, the haggard and touching portraits of Lincoln, the ebullient children and fleeting groups of the young – these evoke in the observer the tenderness and compassion implied by the artist’s own involvement. Her technique, though formidable, and her uses of style and medium; however experimental, never override the flash of mood or sensation. Even in the landscapes, still lives and interiors, this immediacy is present. Her work will speak to anyone who values life and beauty. Stair Galleries

#9 Vandam Street retains a street level door with an oval window above it, a passageway to a former back house or a stable. This is the first address on Vandam, and you may ask, what happened to #1 through #8? The answer is simple. In 1928 6th Avenue was extended south from Minetta Lane to the intersection of Church and Franklin Streets, a downtown realm where no numbered avenues had previously penetrated, along the new cut for the IND 6th and 8th avenue Lines, which were under construction. In a pre-Landmarks Preservation Commission era, buildings were torn down for Progress, no matter how historic they may have been.

Even though it’ll be completely facing 6th Avenue and not on Vandam at all, developers have decided to revive the #1 Vandam designation for a no-doubt overpriced luxury building rising at the intersection.

On this stretch of 6th Avenue between Canal and West 4th Street, there are some surviving medallions honoring the Organization of American States. 6th Avenue was renamed “Avenue of the Americas” by Fiorello LaGuardia in 1945 and the medallions appeared about 1960. Most were taken out between 1990 and 1992 when lengthy stretches of the avenue were repaved and given new lampposts, and the medallions that were taken down were never reinstalled. Most are showing the effects of 5 decades of rust and wear and tear.

“Avenue of the Americas” is a mouthful, and while it appears on letterheads and street signs it never caught on with the public. In the 1990s, the Department of Transportation gave in and installed “6th Avenue” signs.

Back in 2002, I made a survey of the remaining medallions.

Charlton Street

Along with Prince Street, which it “becomes” once it crosses 6th Avenue, Charlton Street is a remnant of British rule in NYC; it is named for British physician Dr. John Charlton, who arrived with the British army in 1762, but later sided with US patriots. He treated Chief Justice John Jay.

#9 Charlton Street is the first house on the street, for similar reasons to Vandam Street. When 6th Avenue was built in 1928, #1 Charlton was torn down: it was a former residence of Clement Clarke Moore, of “A Visit From St. Nicholas” fame; he later owned a lot of territory in Chelsea.

#15 (right) and #17 Charlton, a former residence of acting couple Matthew Broderick and Sarah J. Parker.

Charlton Street, on its north side, retains what is probably the longest row of Federal and early Greek Revival houses in the City. Such continuity of period and such excellent state of preservation is not known to exist anywhere else, even including Greenwich Village and Brooklyn Heights, To walk these streets is as delightful and unexpected a step into the past as to walk up Cheyne Row in London. LPC Designation Report

#19 and #21 Charlton Street

#23 and #25 Charlton; as we have seen on Vandam, #23 once let visitors into aback house or stable. Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay once resided at #25.

#37 and #39, built in 1827, retain iconic Ionic columns at the front entrances, leaded glass in the transom windows and retain their original ironwork. #37 was another Tammany club at one time; Peter, Paul & Mary singer Mary Travers lived at #39 while growing up, and actress Linda Hunt (“The Year of Living Dangerously”) lived at #39 in the 1980s.

#40 Charlton, the Elisabeth Irwin High School, is a 1941 addition to Greenwich Village’s “Little Red Schoolhouse” on 6th Avenue and Bleecker Street.

In 1921, Elisabeth Irwin founded the experimental school at P.S. 16 on East 16th Street in a red-bricked building annex; by 1932, it had moved to another red brick building at 196 Bleecker. It was among the first schools to try field trips, psychological testing, and may other ideas later adopted by mainstream education. The Schoolhouse is now located at 272 Sixth Avenue at Bleecker. The “LREI” on the banners, etc. stands for Little Red and Elisabeth Irwin.

In 2008, LREI acquired adjoining #42 Charlton, one of the 1820s townhouses of the district and one of four originals on the south side of Charlton Street.

#20-24 Charlton, on the south side of Charlton. Singer/actor/activist Paul Robeson was a resident of #24 in the 1930s and 1940s.

King Street

A bona fide Founding Father, Rufus King (1755-1827) who was born in what is now Maine but was then part of Massachusetts, was a youthful representative at the Continental Congress from 1784-1786, a US Senator from New York in 1789, a Minister (Ambassador) to Great Britain from 1796-1803 (where he impressed the still-hostile Brits after the close of the Revolutionary War), a US Senator again from 1813 to 1825, and ran unsuccessfully for President as a Federalist against James Monroe in 1816. In 1805, King purchased and later expanded an existing mansion in the wilds of Jamaica, Long Island, now the King Manor Museum. King, an ardent opponent of slavery, argued: “I have yet to learn that one man can make a slave of another and if one man cannot do so, no number of individuals have any better right to do it.”

Another pair of OAS medallions, for Cuba and Uruguay, at 6th Avenue and King Street.

King Street is the only one of the district’s streets to extend east of 6th Avenue, a half block to Macdougal Street. NYC King of Lampposts Bob Mulero sent me this picture of a castiron lamppost base at King and Macdougal, and it must have survived into the 1990s since I do remember it.

On King Street, Numbers 15 and 17, at 6th Avenue, most clearly retain their original Federal flavor. Although their doors and lintels have been altered, they retain their original pitched roofs, dormers and cornices. The doorways are in their original state, as are their shallow stoops.

#20 King is another well-preserved Greek Revival house of the 1820s.

#19 (right) and #21 King Street. #19 was recently (late 2013) on the market for almost $8M. There are no fewer than 6 woodburning fireplaces within, according to Curbed.

#40-44 King Street. “Their brownstone doorways, strict and linear, their window lintels, their roof cornices with frames, their ironwork with Grecian motifs – their stair railings terminating on handsome columns of brownstone – are all there.” – LPC Report

#45-49 King Street. Simple but effective Federal-style buildings from the 1820s.

#29 King Street, constructed in 1886 (the date is on the parapet) is more recent and much larger than the other houses on the north side of the street. It was built as Public School #8; only eight years after opening, the building was considered inadequate and unsanitary, but PS 8 soldiered on until in 1958 it became the Livingston School for Girls, a last resort for girls thought to be unreachable by other educational methods and disciplines. Finally it was converted to luxury apartments in 1981. Daytonian in Manhattan, as usual, has the whole story.

#41 (right) and #43 King Street. #43 has been altered and now boasts unusual window treatments.

These early multi-unit apartment buildings on the south side of King Street were built in 1901.

An original IND enamel sign was uncovered when a newsstand was removed from the entrance to the West 4th Street station on 6th Avenue. How long will the MTA tolerate such a nonstandard sign? Modern subway riders don’t think in terms of the 6th Avenue and 8th Avenue lines anymore, but of the lines serving this station, the trains with the orange ID bullets, the B, D, F and M, run up 6th Avenue while the ones with the blue bullets, A, C, E, go up Greenwich Avenue and 8th Avenue.

Some information culled from Jim Naureckas’ New York Songlines.

6/29/14