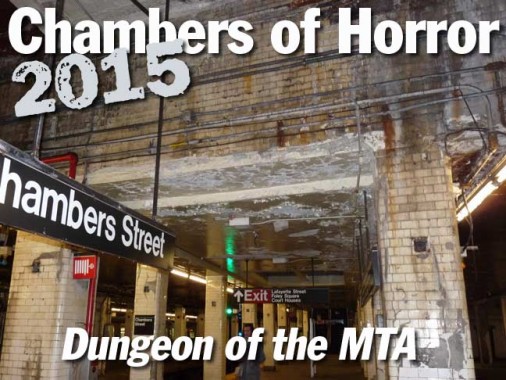

Chambers Street, like Canal, 14th, 34th and 42nd Streets, has stops on the trunk lines of IRT (1, 2, 3) IND (A, C) and BMT (J, Z) trains. By far, however, the BMT Chambers Street is the most decrepit, not only on its particular line, not only on the old BMT, but most likely in the entire system. It is a dungeonlike space, with destroyed walls, disgusting mold, and wonderful mosaics and terra cotta plaques that were once beautiful, but have slipped into utter decrepitude.

On weekends, this is a line terminal, and sits directly under the NYC Municipal Building — one of the seats of NYC government and services.

The BMT Chambers Street station has an adjacent connection to the IRT Lexington Avenue Line (#4, 5, 6) Brooklyn Bridge station. For those interested in seeing the long-shuttered, yet picturesque IRT City Hall Station (seen on this FNY page), you stay on the #6 downtown train as it loops around to the uptown track. I’d estimate that these days, you stand an 8 in 10 chance of not being accosted by train personnel or gendarmes for deigning to sightsee in this fashion.

New indicators and old play a part in this corridor connection. Formerly, black decal letters were applied to tile walls to direct passengers to track connections, or simply to tell them were the toilets were (functioning ones in subway stations are now rare). For a few years now, IND trains (except the #7) as well as the BMT L 14th Street Line, have had trip wires located along the tracks that communicate to platform indicators that tell platform idlers how soon their train can be expected. Along selected IND lines, automated voice announcements are made telling people how many minutes there are until a train rumbles in. Most of the BMT lines are the laggards so far, and have neither.

Other ancient directional signs pointing to the IRT Lex line can be found on platform columns.

As the stygian depths to the platform are negotiated, falling plaster is noted on the towering station ceiling.

The Chambers Street station consists of two center platforms, a surviving wall platform (on the east side) and a destroyed wall platform on the west side. Uptown trains use the eastern center platform and the western track that used to face the destroyed wall platform: now there is a bare-bones, 1960s-era tile wall with station ID. That downtown wall platform was eliminated when the adjacent IRT Lexington line Brooklyn Bridge station platform was extended.

Note the plethora of tiled columns. The BMT Chambers station sits directly beneath the Municipal Building, and in such an occurrence throughout the system, the iron station columns are generally buttressed with extra concrete that is covered with tilework.

Now to the abandoned eastern platform. When the Chambers Street station opened in March 1913, the side platforms were used for exiting the station exclusively,and the station served as the southern terminal. In 1915, the station also began to serve as the terminal for trains coming off the southern tracks on the Manhattan Bridge. Originally, tracks were supposed to connect with el lines running on the Brooklyn Bridge, but that connection was never made.

In 1931, two extra station were added south of Chambers: Fulton and Broad; and the tunnel was extended to connect with the BMT Montague Tunnel, currently serving R trains. After the M train was routed off the Nassau Street BMT and up 6th Avenue in 2010, that connection has not been used in revenue service. The Broad Street station, as well as the 8th Avenue station on the L train Canarsie Line, was built according to standards then in use on the IND stations, with unicolored wall signs and sanserif type. You can see those elements on the right side of this photo. In the 1990s, both stations got makeovers that made them look like early BMT stations, which is more fitting.

From 1913 to 1917, the station also served as the southern terminal for some Long Island Rail Road trains! The LIRR would use BMT tracks on the Williamsburg Bridge, the Brooklyn Broadway el on Broadway and Fulton Street, and use a flyover at Chestnut Street (now the site of the west end of Conduit Boulevard) to Long Island Rail Road tracks on Atlantic Avenue, long before they were placed in a tunnel under the avenue in 1940. The LIRR would then use the Rockaway line, still under its control, and cross Jamaica Bay to the Rockaway peninsula. If only there were this kind of service flexibility today!

The station identification signs, along with those on Canal Street and Bowery, are unusual for the BMT in that they employ sanserif lettering on the mosaics. The diamonds, though, are standard items on BMT decor.

Because the line was originally going to connect to tracks on the Brooklyn Bridge, large T-shaped terra cotta plaques depicting the bridge were installed on the two exit platforms. The plaques depict the East River looking south, with a steamship on the left and Statue of Liberty on the right. The Brooklyn Bridge’s crosswise cables were not part of the design, whether for a lack of money or because of difficulty depicting them.

Large plaques such as this were done by original subway station designers Heins and LaFarge, but by this time Squire Vickers had assumed the mantle. He executed large terra cotta plaques here, but they were more simplified than the ones done by H&F. On Vickers’ later BMT and IRT stations, he designed smaller mosaic plaques as station identifiers, and with the Machine Age IND, dispensed with them entirely.

Among the station’s anachronisms can be considered this 1960s-era analog clock. There are a number of these still kicking around the subway system. Twice per year, they have to be changed by hand for daylight savings or eastern standard time. I can first remember seeing them in the early to mid 1960s.

Chambers Street, of course, has been equipped with standard white on black directional signs that first became standard, with the Helvetica font, in the 1980s.

The side exit platform at Chambers hasn’t been used since 1931, when the line was extended south, and appears to have been given absolutely no maintenance other than the bare minimum since that time. So, you would almost be able to give the Transit Authority, later the MTA, a pass for not maintaining the side platform at all, since no one uses it (a similar situation exists at Hoyt-Schermerhorn in Brooklyn, where a platform servicing trains that used to arrive from the Court Street Shuttle has been closed down; and a center platform at the IND Columbus Circle station has been converted into a walkway — train doors don’t open onto it.

Puzzling, though, in an era when many stations, especially in Manhattan, have been given the TLC treatment with the restoration of station mosaics on the BMT Broadway and other improvements, is why not a finger has been lifted to at least clean the mold off the tiling at Chambers Street.

Doors to nowhere on the eastern platform. These have probably been locked for years and at best, lead to rooms used for storage.

A look toward the disused center platform. A train is preparing to cross over to run uptown.

Though mostly home to newer cars these days, J train regulars can still spot the occasional R-32 (corrugated stainless steel exterior) and R-42 (built like the slant-nosed R-40s, but without the slant). The older cars are expected to be retired within a couple of years.

A view of the side platform, ID and terra cotta plaques, pretty much unmaintained since 1931.

A section of the strip mosaics has worn away here. The MTA is unlikely to spend millions to bring an unused platform up to standard, so there it stands. But why not the rest of the station? It sits at the seat of city government.

Could part of it be that the J spends so little time in Manhattan, and goes to outposts such as Williamsburg (formerly a free-fire zone), Bushwick, East New York, Woodhaven, Richmond Hill and Jamaica?

This tunnel dead-ends north of the Bowery. Tracks here formerly connected to the Manhattan Bridge. Revenue trains on this side can switch over to tracks using the Williamsburg.

More: Joe Brennan’s Abandoned Stations and Pete Dougherty’s Tracks of the NYC Subway at NYC Subways

1/14/15