The forecast was frightful one day in late January 2015, when forecasters were mentioning as many as 30 inches, or two and a half feet, of snow. I was skeptical of this, as it hardly ever snows more than a foot and a half at one time in New York — the city is tucked into a harbor and its seaside status, position rather south of where the worst storms hit, and other factors, mitigate against extreme storms. Still, I sensed this might be my last bit of Forgottening for awhile if enough flakes piled up. Thus I grabbed the Lumix and headed off for a fairly short foray onto Bank Street in Greenwich Village.

My instincts were correct and the storm wasn’t nearly as bad as forecast, but it did usher in several weeks of stone cold weather that only let up around mid-March and prevented me from getting out much, as well as an array of pains that 50+ people know about. Fortunately ForgottenNY has a considerable, though not bottomless, backup, and I’m almost never starved for material. I also acquired a cameraphone, so when I see something, I can shoot something. The cameraphone won’t be replacing the Lumix and its 18x zoom for now, though.

Moving from east to West, Bank Street “begins” at Greenwich Avenue, one of the oldest roads on Manhattan island.

Originally it was part of an Indian trail in the village of Sappokanican that ran southeast and east to about where Cooper Square is today. Another piece of that trail still existing today is Astor Place that runs between Broadway and 3rd Avenue.

Under Dutch rule the road was called Strand Road but by the colonial era the British had made it a military pathway as it ran through the estate of Admiral Peter Warren, the commander of British naval forces during the Revolution. He had acquired several hundred acres of property in the Village in the 1740s.

After 1762, the road was known as Monument Lane or Road to the Obelisk. In 1762, at the spot where Greenwich Avenue meets 8th Avenue today, the British erected a monument to British Major General James Wolfe (1727-1759) who had died in the Battle of Quebec in the Seven Years’ War, but by 1773, before American independence was declared, the monument had disappeared from local maps.

Barraca, on the corner, replaced an Italian restaurant called Artepasta, which had been there for over 30 years.

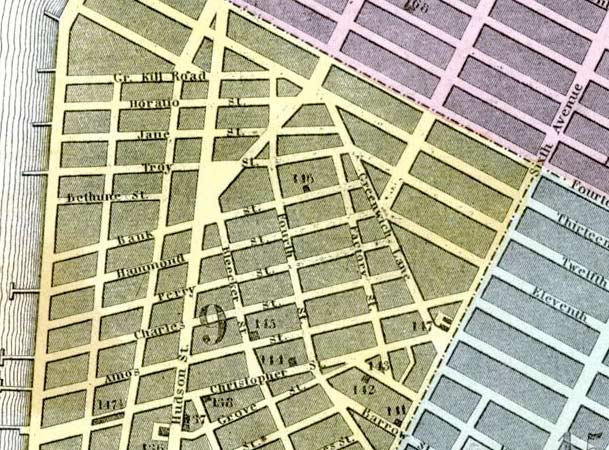

In the first decades of the 19th Century, Greenwich Village’s layout took shape. Greenwich Lane determined the angle of the north-south streets that roughly paralleled it, with the Village’s east-west streets meeting it at a rough right angle. With a few name changes here and there this is still the Greenwich Village street layout, with 7th Avenue South joining the party in 1912. In a few years, Greenwich Lane was promoted to Avenue.

Some streets have changed their names since then: Great Kills Road = Gansevoort Street; Troy Street = West 12th; Hammond Street = West 11th; Amos Street = West 10th; Factory Street = Waverly Place. A full list can be found in FNY’s Greenwich Village Street Necrology.

Though most neighboring streets are named for local personalities in the Village’s early days (one early burgess, Charles Christopher Amos, had three streets named for him) Bank Street is named for one of the oldest institutions in NYC, the Bank of New York, which opened an office “uptown” after a yellow fever epidemic downtown on Wall Street in 1798 prompted a relocation. Several other banks followed suit in 1822 after a second outbreak.

It’s not on Bank Street but it’s certainly in view of it from Greenwich Avenue: the utterly unique Edward and Theresa O’Toole Medical Services Building (formerly National Maritime Union of America AFL-CIO Building—the wavy lines echo sea waves, or half-portholes) constructed in 1964; the white finish was added in 1977. The early 1960s was an era of whiz-bang architecture, with some wildly divergent forms ushered in by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum on 5th Avenue and East 89th in 1959 and continuing through the World’s Fair era of 1965. In NYC, new buildings have been fairly tame and bland ever since.

In the early 2000s St. Vincent’s Hospital acquired the building and, it was feared, would raze it. However, it was St. Vincent’s itself that was razed. This building remains as a medical services center.

Did the weather suddenly clear, or am I using an H.G. Wells time machine? No, I use Google Street View, and I enjoy it, especially when I missed a couple of things on my walks.

As we will see, Bank Street, as with so many other Village, was chockablock full of writers, artists and patrons then as now. This apartment building was constructed in 1927, but before that it was occupied by #1-5 Bank Street. At #5 Bank, Willa Cather (1873-1947) completed several of her great novels depicting Middle America such as O Pioneers! and Death Comes for the Archbishop. She lived at #5 Bank with domestic partner Edith Lewis from 1912-1927.

Factory Street, known for over 150 years as Waverly Place after a novel by Sir Walter Scott, meets its northern end at Bank Street. The building on the right hosts The Waverly Inn, on the SW corner, a semi-private club/restaurant owned by magazine publisher Graydon Carter (Spy, Vanity Fair), known for its $80+ macaroni and cheese (which includes expensive truffles in the recipe). If you’re a well-known name you can get in easily, but it’s not quite as easy for the hoi polloi. The phone number isn’t listed, so no reservations are taken. There has been a restaurant/tavern on the site since 1920.

Across the street is #11 Bank Street, where novelist John Dos Passos (1896-1970) wrote Manhattan Transfer in 1925.

I must admit, I haven’t read much Dos Passos, a socialist who later became a right-winger, but as a pop music fan, I do know about the Manhattan Transfer.

The house partially shown on the right, #9, was briefly the home of controversial poet/critic Ezra Pound (1885-1972) during a 1969 visit with renowned publisher James Laughlin.

The row of Greek Revival townhouses on Bank Street’s south side, #16-34, between Waverly and West 4th, is considered among Greenwich Village’s finest. They were built in 1844-1845 for developer Stephen Peet, who purchased the property from the Bank of New York.

Pictured are #20 through #26. Publisher Graydon Carter owns #22, first from left, while roving newsman Charles Kuralt lived at #34.

#21 and #23 Bank are part of another row of townhouses, built in 1856-1857, by Linus Scudder, who built many such in the West Village. #21, right, stands out from the pack as it was altered considerably in 1893 by the Christian Reformed Church, and later from its use as a political club. Note the small faces on either side of the building above the third floor.

#23 Bank turns up as an address in Caleb Carr‘s historical novel The Alienist.

#31 Bank Street is a transitional “brickstone” with a brownstone clad ground floor and the top 4 floors possessing a brick exterior. It was built in 1891 and combined Romanesque and eclectic Queen Anne elements.

#37 Bank Street, a Greek Revival townhouse, predates the other buildings on the block. It was constructed in 1837 for downtown leather and shoe merchant Jonathan Ransom.

What have they done with that stable at #48 Bank? Constructed in 1910, it was “modernized” in 1969 by an owner indifferent about light, unless there’s a large skylight.

ON the NW corner of Bank and West 4th Street is Hamilton’s, a self-described soda fountain and luncheonette reminiscent of the old days. The prices are not outlandish, as I had expected, and I may visit within soon. The building dates to 1898 and inside is a salvaged classic soda fountain. Reviews, as usual, are all over the place.

Doors marked WOMEN are usually restrooms, but on the NE corner of Bank and West 4th, the name marks an accessories shop under the Marc Jacobs aegis, which runs several boutiques in the West Village.

The southwest corner of Bank and West 4th features an apartment building/laundromat combo, likely dating to a couple of years either side of 1920.

#56 Bank Street, on the south side just west of West 4th, was in the news early in 2015 when it was left by longtime New York Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter, who played for 20 years between 1995 and 2014, winning five World Series rings. The 2 bedroom, 2.5 bath digs rents for about $23K per month, but the Captain could easily afford that. The Greek Revival house dates to 1833 when it was built for Reverend Joseph Carter.

#63 Bank Street, on the north side between West 4th and Bleecker, was where the Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious died of a heroin overdose in February 1979, awaiting trial for the murder of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen, who was found with a hunting knife thrust into her stomach in October the previous year at the Chelsea Hotel.

Sid wasn’t an original Sex Pistol. He was brought in after bassist Glen Matlock was increasingly involved in fights with Johnny Rotten, even though Sid wasn’t previously a musician.

Sid’s rendition of the Paul Anka/Frank Sinatra classic “My Way” bruised eardrums worldwide in 1978 in the film The Great Rock & Roll Swindle. The performance ended with Sid shooting several audience members.

#62 (left) and #64 Bank Street. #62 dates to 1836, while the taller #64 to 1841. Both still use window shutters to block out the morning light, which can be intense at certain times during the year.

#72 (left) and #74 Bank Street, were constructed in 1839 and 1842, respectively, for local Builder Joseph Lockwood, as were #62 and #64.

#76, more or less a twin of #74, was built in 1839, 3 years before #74, also by Lockwood. Aside from the other fine details, both houses feature tiny square attic windows.

#69 Bank Street was the original home for the renowned Bank Street School for Children, founded in 1916 in this edifice built in 1905 for Gustave Schirmer. It has moved uptown to the Columbia University area and is now the Bank Street College of Education.

Lauren Bacall (1924-2014) looked as sophisticated and mature at age 17 (when she lived in an apartment here at #75 Bank Street in 1940 with her mother) as she did later in her modeling and film career. She spent her final years at the Dakota Apartments on West 72nd Street and Central Park West. That was the building where John Lennon and Yoko Ono lived for many years (more on them later, in Part 2).

This Moderne building is one of the newest on Bank Street, on the corner of Bleecker, and it went up in 1938. It is also called #9 8th Avenue, the avenue’s first address.

Bank Street looking west from Hudson Street. The street is actually interrupted by a block by the Bleecker Playground, in the southern triangle formed by the “X” created by traffic engineers here. Hudson Street northbound traffic is routed onto 8th Avenue, while Hudson Street is cut off by Bethune and its southbound traffic routed onto Bleecker.

Knowing the White Horse Tavern is nearby, whose exterior I can’t resist photographing, I went south on Hudson for a block to West 11th. The bar on the corner, the Philip Marie, styles itself as “one of the most romantic restaurants in NYC.” Reviews are generally good. So far I don’t know what the name is about.

Next door is a former storage warehouse no longer used for that purpose; but the trend of late is to repaint faded signs indicating a building’s former use!

I have only actually been in the White Horse once. It dates back to 1880 but was truly “popularized” when a literary light died there. Here’s what I wrote about it back then:

The White Horse Tavern is another of NYC’s long-lived literary hangouts, and yet another with an ancient neon sign. It has been here on Hudson Street and West 11th since 1878, replacing the James Dean Oyster House. And one of the White Horse’s patrons was indeed too fast to live and too young to die.

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) was born in Swansea, Wales and surprisingly enough, did not visit the USA until 1950. Thomas first came to prominence as a poet with Eighteen Poems in 1934; his most famous work is perhaps “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night.” His prose works include A Child’s Christmas in Wales and the play Under Milk Wood, both published posthumously in 1954.

Without getting into a clinical or psychological tangent on a Forgotten NY page, a field your webmaster is more suited as a patient than as an analyst, it’s a conundrum that has lasted throughout the centuries: why are so many of our most creative individuals given to dissolution and self-destruction? Thomas, the story goes, drank himself to death at the White Horse in November 1953, but the story is more complicated than that: the writer had been quite ill that year, and a number of factors likely contributed to his demise.

A visit to the White Horse today provides a relaxed atmosphere, especially in the front room where you watch the Village go by out the window. Check for how many representations of white horses you can find!

Modern liquor store signage on Hudson Between West 11th and Bank Street. Modern fonts such as Helvetica and Futura are used, so the signs can’t be that old, but they can potentially last for decades.

Bank Street, looking west from Hudson Street.

More on Bank and its partner, Bethune Street, in Part 2.

3/15/15