I think this one is going to take a number of pages to finish. In December 2014, before the winter got really harsh, I decided to walk around certain parts of NE Staten Island I had missed as well as revisit parts of the local neighborhoods I had already visited, but not lately. The page is going to have to be a bit picture -heavy because printed information on Staten Island, a borough in one of the largest cities on Earth, remains largely sketchy.

In my collection of NYC books I think I can count the number of books on (exclusively) Staten Island with two hands. There’s Holden’s Staten Island, Secret Places of Staten Island, any one of John Sublett’s self-published Staten Island books, and Staten Island neighborhoods in the Arcadia photo books series. Not one of those books are on a major publishing house imprint (though Arcadia does have hundreds of editions nationwide). In my edition of New York City Landmarks, Staten Island takes up 35 pages out of 452; in the AIA Guide to New York City, Staten Island takes 53 pages out of 1056. In Forgotten New York the Book, I give Staten Island what I feel is a decent portion, 55 pages out of 360.

Many Manhattan tour guides deliberately and cruelly give Staten Island “short shrift,” as well, and routinely dismiss and insult the Island Borough.

In all books that deign to discuss the boroughs outside Manhattan, Staten Island comes last in the backs of the books. It does so in my book, as well, but that’s because in my book I discuss the boroughs in alphabetical order, Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, Staten Island. Blasphemy!

So I walk the Staten Island hills, snapping away at anything remotely interesting, and consult the wilderness of the world wide web for any scattered information. Other methods would be to consult Staten Island libraries and museums. Living in Little Neck, Queens that’s not often a practical consideration. The New York Public Library has hundreds of images of the island in prior decades. And, well, as far as I know, that’s it. While other boroughs’ street names and the stories behind their names have been published in a number of works, Staten Island’s (and Queens’) remain unchronicled. It’s unlikely a publisher would get much of a return on its investment for printing anything called the street Names of Staten Island, though I have in my collection editions for not only Manhattan, Brooklyn and Bronx but also Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco and even Houston, a town I’m not likely to ever see (unless there’s a lamppost convention or something).

Off I went and I was determined to walk plenty of streets that the AIA Guide or NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission people have never been.

GOOGLE MAP: St. George—Tompkinsville—Park Hill—Stapleton

When the new Staten Island ferry terminal opened in early 2005, a new bay-side walkway was opened that connected the terminal to an older walkway along Richmond Terrace as far as Westervelt Avenue. Besides views of the Shining City across the water, the walkway runs past Staten Island’s 9/11/01 as well as Richmond County Bank Ballpark, home of the Class A Staten Island Yankees. On the left side of the picture is the approximate location of location of the New York Wheel, the largest ferris wheel in the world (scheduled to be approximately 60 stories tall and set to open in 2017).

On the left is the Castleton Towers housing project, the current tallest buildings on the island.

Said Shining City as seen from the walkway with #1 World Trade Center in the middle.

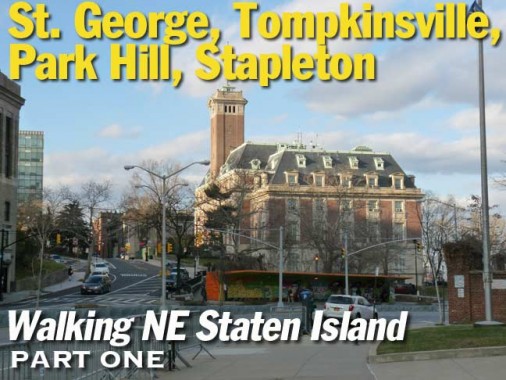

The title card (sorry you can’t see it on a mobile) shows Staten Island’s Borough Hall, the most impressive of the “outer borough” Borough Halls, looking north from Bay Street.

The magnificent John Carrere and Thomas Hastings French Renaissance edifice was completed in 1906. It houses the Borough President’s Office, offices of the Department of Buildings and other civic offices. On the inside, the grand marble lobby contains a series of significant WPA reliefs and murals painted in 1940 by Frederick Charles Stahr, illustrating events in Staten Island history.

I only seem to get to Staten Island on weekends, hence I’ve never seen the murals in person. Staten Island USA, though, has plenty of images (see them on this site while you can since websites have a habit of disappearing over time, except, of course, this one). Space for the murals had been designed by Carrere and Hastings and included in 1906, but there was a lack of money and the murals didn’t arrive until 1936, when Stahr petitioned the WPA for funding.

In the magnificent coffee table book Murals of New York City (Rizzoli, 2013) Glenn Palmer-Smith says:

Painted in an idealized swashbuckling storybook style, the series of paintings begins with the 1524 discovery of the island by Giovanni da Verrazzano and goes on to tell all the myths we’ve all agreed upon, or what is called history. Next is a panel of Henry Hudson, arriving in a Dutch ship in 1609 and giving the island a Dutch name, “Staaten Eylandt,” to satisfy his investors. The next two panels depict the native Lenape tribe and the first invasion of the colonial real estate developers… As the suite progresses, the French Huguenot farmers gradually dominate the island. The next panel shows the British admiral Richard Howe taking charge of the island and the building of Fort Hill. The next painting shows the only attempt at a peace conference during the Revolutionary War, between Admiral howe and a contingent of writers and signers of the declaration of Independence, including Benjamin Franklin and John Adams.

The series ends with the last panel showing the construction of the Bayonne Bridge to New Jersey.

If they think about it at all, I suppose, most people think that St. George is named for St. George, the semi-mythical protector of England who slew a dragon. This is actually an error (that I made for years before researching it; there was a real St. George and he came from Greece in the third century AD). Staten Island’s Saint George was named for a land baron named George Law, who had acquired waterfront rights at bargain prices. He agreed to relinquish some of the rights for a ferry terminal – provided it be named for him!

In the triangle formed by the angled intersection of Stuyvesant Place and Bay Street you will find a statue of a Roman legionnaire, carrying a spear and shield with his right hand stretched out to the north. This is a memorial for Major Clarence Tynan Barrett, a Civil Warrior from Staten Island who served what was in his day the independent county of Richmond in various roles.

Barrett (1840-1906) studied landscape architecture until the outbreak of the Civil War, when he signed with the 175th New York Volunteers regiment. He worked his way up through the ranks and was eventually promoted to captain and aide-de-camp of the United States Volunteers. He earned the rank of Major after serving gallantly during the Union siege of Mobile, Alabama.

Barrett was involved in the battle at Richmond, Virginia, which signaled the end of the War in 1865, after which he returned to Staten Island, establishing himself as an expert in his chosen fields of profession, landscape architecture and sanitation engineering. Barrett was also eager to contribute to public service, acting as Police Commissioner for seven years and as Superintendent of the Poor for five years.

The bronze classical warrior figure on a marble pedestal by Sherry Edmundson Fry (1879–1966) was given to the City by Barrett’s widow, Anna Hutchings Barrett. It was unveiled on November 11, 1915 near Boro Hall and moved to its present location in 1945. NYC Parks

You will find a disused fountain and a celebratory inscription on Barrett’s service in the rear of the monument, worn nearly illegible by time on marble, which doesn’t hold up well to weathering.

The west side of Bay Street, which is the main drag along or near the Staten Island waterfront along Upper New York Bay, is a graveyard of sorts for old banks. #26 Bay Street, I’m told, was the Staten Island branch of the Corn Exchange Bank, which after a few mergers is now part of JP Morgan Chase. #26 has a couple of bronze (by now green with verdigris, like Lady Liberty) plaques on the front of the building indicating a real estate and insurance broker, Kolff & Kaufman, as well as a night deposit slot.

It turns out that Cornelius Kolff (1860-1950), one of the partners, was an interesting cat. He wrote a book in 1939 called “Staten Island Fairies” (about, of course, mythological creatures like Puck or Tinkerbell) and also built a log cabin he called the “Philosopher’s Retreat” a few miles away from St. George in Emerson Hill, a place he could get away and convene with nature, like Henry David Thoreau. In fact Kolff helped develop the neighborhood and gave it its name, since Dr. William Emerson, brother of philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, a Thoreau contemporary, made his home there in the mid-19th Century. Kolff later had a Staten Island ferryboat named for him (scrapped in 2003).

Most old banks of a certain age have night deposit slots. Someone tell me how these worked — I can’t imagine it being as simple as walking up with a roll of bills and a deposit slip and dumping in the Benjamins and Andrews.

Next door, #28-30 Bay Street is another former bank, but this time I don’t know which one. It too has a night deposit slot along with a prominent burglar alam (#26 has a “vault alarm” on the side of the building; I didn’t get a photo). #28 is now the “S.I. Education and Employment Consortium” which “provides employment counseling, training, skills and placement services to needy and disadvantaged residents of Staten Island.”

The center traffic median on Bay Street is jazzier than the usual, with wrought-metal undulations suggesting water waves.

St. George’s post office, the largest in Staten Island, was likely built in the 1930s. It features two massive ornamental lamps by its front staircase. It was named the Sergeant Angel Mendez Post Office in 2011 after a Vietnam War hero who was raised at the Mount Loretto orphanage.

Skipping ahead to Victory Boulevard and Bay Street, this stolid brick building from the late 19th Century for decades suffered the indignity of being encased in a decorative metal cage (does anyone have any photos of this?) Thankfully it was removed about twenty years ago.

On the Central Avenue side of the building is an advertisement for marital aids, while a spray painted stenciled admonition reminds me of a 1980s song from The Godfathers.

Meanwhile, across Victory Boulevard, New York City is surprisingly lacking in Spanish-American War Memorials (and will there be any for the various Middle east conflicts that began in 1991, I wonder?) The situation is assuaged somewhat by The Hiker, which greets travelers pressing west on Victory Boulevard.

The Hiker statue sculpted by Allen G. Newman that honors the local soldiers of the Spanish-American War (1898-1902) is still prominently displayed in the park. The statue was modeled after foot soldiers who participated in long marches in the Cuban terrain. In the War, the United States allied with the Cubans to defeat the Spain for control of colonial power in the Western hemisphere. The Hiker in Tompkinsville Park was the official monument of the United Spanish War Veterans and was located in front of Staten Island Borough Hall. The statue was moved to Tompkinsville Park in 1925 after a series of cars hit the statue. NYC Parks

On the Bay Street side of Tompkinsville Park, a boulder is inscribed with a marker placed in 1925 by the Daughters of the American revolution identifying the spot as “The Watering Place,” where early travelers in the colonial era replenished water stores from a freshwater spring, which has since been relocated in the sewer system.

The park is named for a small town founded in 1815 by a future Vice President, Daniel D. Tompkins, while he was the Governor of New York State. He established a ferry service to Manhattan in 1817, possibly from a landing at Victory Boulevard, and founded the Richmond Turnpike Company as an expedited means for wagons to travel to Philadelphia and elsewhere on the East Coast; the turnpike, called Arietta Street in Tompkinsville and Richmond Turnpike the rest of its length, was renamed Victory Boulevard after World War I. Tompkins was elected Vice President on the ticket with James Monroe in 1816, and served two terms. He died here in Tompkinsville just 3 months after leaving office and is buried in St. Mark’s Churchyard on 2nd Avenue and East 10th Street in Manhattan; nearby Tompkins Square Park also bears his name, as well as Tompkins Avenues in Staten Island and Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

Daniel Tompkins’ wife, Hannah Minthorne Tompkins, and children, are or were also remembered in Tompkinsville’s street layout. His children were named Hannah, Arietta, Sarah Ann, Griffin and Minthorne. Originally, streets in Tompkinsville bore their names; today, Van Duzer Street has replaced Sarah Ann Street, Bay Street has replaced Griffin, Sarah Ann by Van Duzer, Arietta by Victory Boulevard, but Hannah and Minthorne Streets are still in place. Hyatt Street is likely named for Tompkins’ mother, Sarah Ann Hyatt Tompkins. Daniel Van Duzer was a Tompkinsville landowner in the 1830s, with Van Duzer Street running through what used to be his holdings.

In 1836 Minthorne Tompkins (the son of Vice President Daniel Tompkins) and merchant William Staples established a ferry to Manhattan and founded the village at Bay and Water Streets. German immigrants built numerous breweries in the area in the 1800s including Bachmann, Bechtel, and Piels, whose brewery was in business on Staten Island until 1963. The region south of Tompkinsville took on the name Stapleton in William Staples’ honor.

There probably aren’t many NYC Parks that retain their original bathroom facilities, at least buildings preserved largely intact from when they’re built. The NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission likely won’t be taking a look at any of these gems anytime soon, but I do. This one in Tompkinsville Park boasts a nice Spanish Mission tile roof, a row of arched windows, and one of the original pendant lanterns, long out of service, above the men’s entrance. Nature wasn’t calling and I did not inspect the interior.

I stalked off up Swan Street, which has a curious bend in the middle and its own unsung specimens of interesting architecture…

… such as this small house at #45 that nonetheless has a full porch on each of its two floors. Perfect spot to relax no matter what floor you’re living on.

Midblock on Swan Street, at the bend, there’s a shambling, barn-like structure that is nevertheless gabled and dormered, and an incredibly worn sign marking it as a NYC Sanitation Department Encumbrance Depot. Garbage trucks are parked in the adjoining lot.

A few years ago, when ForgottenTour 16 was swinging through Tompkinsville, Staten Island, we saw this ancient barn-like structure on Swan Street, labeled “Encumbrance Depot” and wondered what it was.

Secret Staten Island (the link has since been removed — why is stuff taken down?) has come up with the answer, now that it’s semi-endangered now (every old building on Staten Island is semi-endangered):

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the Department of Street Cleaning (later to become the Department of Sanitation) primarily used three types of vehicles to help insure the cleanliness of Richmond Borough: the Garbage Truck, the Ash Cart, and the Street Sweeper. This being before the widespread use of motor vehicles, they were all horse-drawn.

To house the horses, the City built two stables on Staten Island, simply named Stable “A” and Stable “B”. Stable A was built in 1902 on Swan Street, Tompkinsville (as of this writing we have yet to determine where Stable “B” was located) and between the two they housed over 70 draught horses; the “engines” that ran the vehicles that kept the island clean. Stable “A” witnessed the transition from “old” technology to “new”: twenty years or so later, the horses and their vehicles were replaced with more modern gas-powered vehicles. Neighboring properties were purchased and the area was enlarged so that the barn and surrounding lots were (and continue to be) used as a storage area for various Sanitation equipment and vehicles.

A nearby 2-family house shows off a window treatment the architectural experts call a “polygonal bay,” or a window that sticks out in two places with two angles.

I am a fan of clock towers, and the old PS 15 at St. Paul’s Avenue and Grant Street fills the requirement nicely. In 2008 it became PS 65, the Academy of Innovative Learning. Originaly called the Middletown Twp. District School #1, it was completed in 1897 by architect and Staten Island resident Edward (né Ebenezer) Alfred Sargent (1842-1914), who designed many of the eclectic homes found along St. Mark’s Place in St. George. Sargent was also a noted painter. (Tragically a Sargent masterpiece in Westerleigh was demolished in 2008).

I found an aged “no smoking” sign on narrow Grant Street between Van Duzer Street and St. Paul’s Avenue.

Tompkinsville and Stapleton feature neat, tidy “saltbox” houses with pitched roofs that would not be out of place in small-town New England. On the left, Clinton and Van Duzer Streets; on the right, Clinton and Brewster Streets.

Brewster Street runs for one block between Clinton and William Streets, with an inexplicable dead end past William. Here’s another twin-porched dwelling with an unfortunate choice of iron porch railings, but as Pope Francis said, who am I to judge.

The steep hills (we are on a downslope from Wards Hill at this spot) necessitate some unusual configurations, like this house with the garage on the first floor, porch on the second.

This is a rambling, ramshackle old pile on the east side of Brewster Street. It’s surrounded by a plywood fence, and I (apparently) defied the wishes of the owner and stuck the camera over the fence to obtain this shot.

The property is neighbored by a fairly large, empty grassy lawn. The lawn is bordered by a lengthy stretch of bluestone sidewalk, pretty much broken into pieces by now, since it’s over a century old.

I have crossed into Stapleton — the street plan is still largely as it was shown on this 1873 map.

Yawning as I’m writing this at 12 midnight Sunday, from sleep not boredom, so my first pass through Stapleton on this walk will wait till Part 2.

5/10/15