Forgotten NY contributorThe “forgotten” appendage of the city, the Rockaway peninsula has a number of communities strung together by an elevated subway: Far Rockaway, Wavecrest, Edgemere, Holland, Seaside, and Rockaway Park. Among the smaller neighborhoods, Hammels lacks its own el station, sandwiched between a revitalized Arverne and a resilient Holland. Not much too see here, right? I’ll try to prove you wrong as we take a tour.

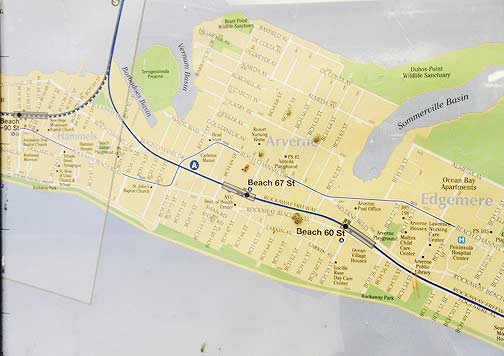

Hammels appears on this subway station map, sitting just below a split (known as the Hammels Wye) in the Rockaway subway line. The street grid below the Beach 67 Street station has since been replaced with Arverne By The Sea, a suburban-style development with its own street scheme. Arverne and Hammels got their names from their founding developers, Remington Vernam for the former and Louis Hammel for the latter.

As for Holland? It’s not about the country, it’s about developer Michael Holland. The Holland Tunnel of Manhattan also has a human namesake: engineer Clifford Holland.

Between the 1970s and 1994, an unusual subway shuttle, the H train took straphangers from Brooklyn’s Euclid Avenue to Rockaway Park, then backtracking towards Far Rockaway, and then back to Brooklyn.

It was a one-seat ride from Rockaway Park to Far Rockaway, but not the other way around. For that direction, riders had to transfer at Broad Channel.

With few riders taking the peninsular shuttle, it was discontinued. Today, a 4-car S shuttle runs between Rockaway Park and Broad Channel.

The city’s two other S shuttles are the Franklin Shuttle in Brooklyn and the Grand Central Shuttle in Manhattan.

What appears to be a retirement palace faces the tracks, with its neoclassical facade hidden by newer additions. A one-block street called Java Place makes a slight diagonal onto the Rockaway Freeway, a one-lane speedway underneath the tracks. It has stoplights, but allows few turns, discouraging local traffic.

The bay side of Hammels is a mix of 19th century summer homes and more contemporary brick boxes out of a contractor’s catalog. Some 19th century maps label this section as Oceanus, but this name is forgotten today.

Older maps show a series of tight streets and homes on stilts. Most of those homes are gone, and some streets were never built. Jamaica Bay is the semi-round body of water that separates the Rockaways from mainland Queens. Once slated to become a major seaport, the bay is today largely left alone as a wildlife refuge.

Next door to its office, constructed in 1907 at Rockaway Beach Blvd. and Beach 90th Street, a cream-colored tower has just been finished. In many beach communities, the color of the buildings resembles sand. It’s like living in a giant sandcastle!

This Catholic Charities center is on the border of Hammels and Holland, but claims to be in Seaside. The borders of Rockaway communities are very fluid, and it’s sometimes hard to tell where one ends and the other begins.

Is it possible that the same seniors who eat here once danced the Lindy Hop and foxtrot in the same place?

Shore Front Parkway borders the boardwalk between Beach 73rd and Bach 108th Streets. Designed by master planner Robert Moses, it displaced hundreds of bungalows, isolating the neighborhoods from the beach. But that was only the beginning. Moses sought to build a high-speed parkway for the peninsula, but community opposition killed it.

St. Rose of Lima, Beach 84th and Shore Front Parkway, has been the local Catholic parish since 1886. Once surrounded by Victorian summer homes, it later stood alone near the sand. Later, high-rise housing has kept the church company. Its namesake is the first South American-born Catholic saint, famous for fasting 3 days a week, taking a vow of virginity against her parents’ wishes. She cut her hair and mutilated her face because she resented her physical beauty. The vegetarian ascetic predicted her own day of death at age 31 in 1617. She was canonized in 1671 and serves as the patron saint of Peru, Philippines, and Latin America.

Haven Ministries (188 Beach 84th) did not design this sanctuary. Well into the 1990s, this was Temple Israel, and the window guard, star above the door, and cornerstone all testify to the building’s Jewish builders. This building replaced an earlier Reform shul destroyed in a 1920s fire. As the peninsula slid into a postwar decline, so did its Jewish population.

In recent years, Far Rockaway’s Orthodox community has seen a resurgence, as a low tax alternative to the neighboring Five Towns. On the western end, Belle Harbor and Neponsit also have strong Jewish communities, anchored to Brooklyn.

The Orthodox congregation Derech Emunoh has served Arverne since 1906. It once had a palatial Georgian-style sanctuary on Beach 67th Street and Larkin Avenue (2000 photo, left) that fit 800 congregants.

As Arverne declined, so did the synagogue. But with each urban renewal scheme, there was hope of a revival. But weather, vandalism, and arson took their toll. The old synagogue was destroyed in a 2002 fire. Since 2002, the developers of Arverne By The Sea granted the few remaining congregants a trailer on their property as a temporary shul. Failing to secure new members and a permanent space in Arverne, the century-old congregation folded in September 2009.

As Arverne continues growing, perhaps Jewish families will return and give new life to the now-defunct Derech Emunoh.

After years of false starts, Arverne By the Sea (between Beach 63rd and 73rd Streets along the waterfront) is welcoming its first residents. Taking on new urbanist designs, it has winding streets, pergolas, picket fences, and its own street signage. You can drive, but not park on these streets. Below is a design of the overall area, by the architects Ehrenkranz, Eckstut & Kuhn.

When I was a student at CCNY, I remember being fascinated by Prof. Michael Sorkin. His Arverne proposal turned the grid into circles, had windmills atop apartments, and a park at the center of this new village. Sorkin’s plan did not make the cut, but the cone-shaped roofs still look smurfy to me.

Some critics say the Smurf community is communist. Sorkin is also an outspoken leftist. Birds of a feather, I suppose.

Michael Bell’s Stateless Housing design hearkens to the past century with a strict street grid containing boxy buildings. Bell teaches at Columbia University. Between these two losing proposals, I’d go with Sorkin.

This aerial shot shows the gap between Wavecrest and Hammels (bottom) known as Arverne By The Sea.

There is already tension developing between the older bayside Arverne residents and the seaside newcomers on the neighborhood’s identity. Some older residents fear that with so much attention paid to the new neighborhood, the older areas north of the tracks are being forgotten by the city.

The sandy wasteland was once a dense colony of bungalows, containing three mid-block alleys. They will soon disappear, but under construction are new alleys with fancy names like Spinnaker Drive, Aquatic Drive, Beach Breeze Place, and Sandy Dune Way.

In the background of the eastward facing aerial is Silver Point of Long Beach Island, and further back is Jones Beach. The current gradually carries the sand to the west, and groin piers are an attempt to slow the flow of nature to preserve the landscape.

The aerial surveys above are from 1954, 1980 and 2009. They show Arverne’s transformation from a bungalow city to a wasteland to a coastal suburb. The only constants here are the ocean, Rockaway Beach Boulevard, and the elevated railroad.

The most recent incarnation of Arverne asserts its independence by breaking from the monotonous street grid.

The story of Rockaway is one of decline, attempted revivals, and its gradual rebirth. In 1978, Daily News writer Bernard Rabin had a series of articles on the peninsula’s history.

The first Cross-Bay Bridge opened in the 1920s, a rickety wooden structure. In 1939 a four-lane drawbridge replaced it.

The current fixed arch span opened in 1970. By then, plans for an ambitious seaport in the bay were long retired, and the bridge has a clearance of only 55 feet.

At the time, Arverne was a wasteland of uncertainty, and Hammels was a crime hotspot. Rockaways’ Playland was slowly approaching its 1985 demise.

The post office for Holland is listed as Far Rockaway. The local public library doesn’t take sides, simply calling itself Peninsula.

Between 1886 and 1940, Hammels had its own Long Island Railroad Station at the junction of the Far Rockaway and Rockaway Park branches.

The photo on the left is from Far Rockaway.com and below left is from aRRt’s Archives.

When the railway was elevated in 1940, the station was eliminated. The brick substation building is still there today.

Its stations have double names — the cross street number and older pre-city names such as Gaston, Straiton, and Playland.

Rockaway Beach Boulevard once had trolleys to supplement the railroad. The Ocean Electric Railway trolleys disappeared before the war.. Urban renewal schemes widened the boulevard, but also reduced its commercial strip appearance. The road runs from Beach 35th Street to Jacob Riis Park.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

The Wave newspaper

SOURCES:

“Rockaway project gets some stimulus” By Hilary Potkewitz Crain’s New York Business 9/27/2009

“Rockaways to rise above blight” By Hilary Potkewitz Crain’s New York Business 6/8/2008

“In Faded Beach Community Seeking Rebirth, Projects and Luxury Homes Meet” By Corey Kilgannon. New York Times 1/7/2007

“Perspectives: The Arverne Plan; Oceanfront Site Terms Challenge Builders” By Alan S. Oser. New York Times 11/20/1988

“City opens its biggest plot, in Arverne, to development” By Mark Sherman. New York Times 3/11/1984

“Rockaway Sets Sights for Big Economic Boom” By Bernard Rabin NY Daily News 1/31/1978

“WWI Slowed the Boom in Rockaways” By Bernard Rabin. NY Daily News 1/14/1978

“Ocean Electric Railway” aRRt’s Archives

“Between Ocean and City” By Lawrence Kaplan and Carol P. Kaplan. Columbia University Press 2003

“Old Rockaway, New York, in Early Photographs” By Vincent Seyfried and William Asadorian.† Dover Publications. 2000

Forgotten NY contributor Sergey Kadinsky is a freelance writer, teacher, tour guide and photographer. sergey.kadinsky@gmail.com

Page completed May 21, 2011