By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

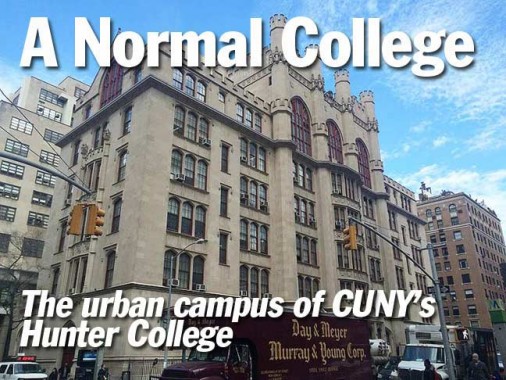

New York City has more colleges than any other city in the country, ranging from leafy academic villages such as Brooklyn College and Fordham University, to vertical urban campuses such as Baruch College and John Jay College. Then there is Hunter College, a collection of buildings that house the second oldest unit within the City University of New York. Hunter had its start in 1870, when the state legislature authorized the creation of a public college for women to serve as a counterpart to the all-male City college (CCNY), which was founded 23 years earlier.

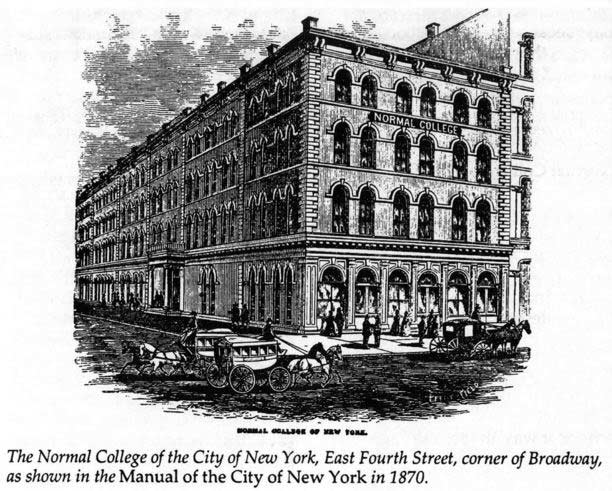

Together, the Female Normal High School and the Normal College of the City of New York would educated young women according to the “norms” of the time to become qualified teachers. In its first three years, it shared space with a dry goods store at East Fourth Street and Broadway. As its student body grew, it moved uptown to Lenox Hill into its own proud Collegiate Gothic campus.

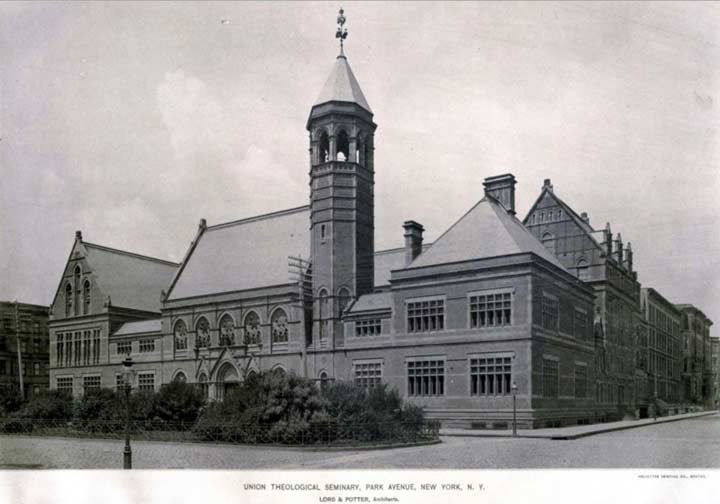

The neighborhood of Lenox Hill, named after early 19th century landowner Robert Lenox at the time was an anchor for numerous academic, charitable, health, and religious institutions, including Union Theological Seminary, the Chapin Home, and New York Foundling Asylum. As the neighborhood was becoming more crowded and land values rose, these institutions either migrated further uptown or out of Manhattan.

Now let’s fast forward in history and visit the campus as it is today. The easiest way to find Hunter College is by subway, which share’s the school’s name. It is one of four stations in the city that indicates a higher learning institution, the others being Columbia University, City College, New York University, Brooklyn College, and Lehman College. The station opened in 1918 and had an extensive reconstruction in 1984, resulting in Squire Vickers tiled platforms and a modernist mezzanine. On the platforms, the multiple gray signs indicate that there are still many nonprofits based in the neighborhood.

The architect of the reconstruction, Ulrich Franzen & Associates, connected the station directly to the college, where the firm designed the West and East Buildings earlier in the decade. At the station’s southwest entrance, a tree is enveloped by a staircase leading into the West Building. Looking up, one sees the third floor sky walk that connects three of the campus’ four buildings.

Across Lexington Avenue, the much humbler southeast entrance features decorative lettering not seen in any other subway station.

Hunter College’s namesake was its first president Thomas Hunter (1831-1915).

Shortly before Hunter’s death, Normal College was renamed after him, as well as the only remaining building on campus that dates to the college’s previous name. Completed in 1911, the Collegiate Gothic structure was designed by prolific public school architect Charles B. J. Snyder as the first building in a never-realized plan for a much grander campus block. Like its brother campus at City College, Thomas Hunter Hall features numerous grotesques around its façade, along with cathedral-style windows.

It must have been luck that a moving truck decorated with Gothic letters was driving past Thomas Hunter Hall as I was taking this photo. It reminds me of pre-war Germany, when the Gothic-like Fraktur font appeared everywhere — books, newspapers, advertisements — as a way of asserting the country’s identity. As Bismarck once said, “I do not read German books in Latin letters!”

When the Nazis came to power, they debated amongst themselves on the merits of Fraktur, Antiqua and Broken Grotesque fonts. Having ruined the reputation of the swastika, the same happened with the old Germanic fonts, which fell out of use after the war.

Compared to Thomas Hunter Hall, Ulrich Franzen’s East and West Buildings are modernist with no exterior embellishments. Their defining features are the two skywalks, connecting the seventh and third floors. Lacking a campus quad, Franzen provided for a rooftop terrace on West Hall. The precedent for rooftop student space can be found at the college’s North Building, which stands on the site of the old Main Building of Normal College and gives Hunter College its Park Avenue address.

On the East 68th Street wall of the North Building, the school’s commitment towards diversity is exemplified by a Ralph Waldo Emerson quote. North Building’s designer was the firm of Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, in consultation with Harrison & Fouilhoux. If the façade appears familiar, the main designers also built the Empire State Building. Like their famous superlative skyscraper, North Building set records in its day, with capacity for 5,600 students in 112 classrooms, along with four gyms, auditorium and swimming pool. Built between 1936 and 1940, its bare exterior could not be further in appearance from the old Normal College structure.

As the college has very tight security and I did not have an invitation to see the campus, the only photos I was able to find of North Hall’s rooftop terraces from yearbook photos taken in 1975 and 1978. The terraces offer students the view of a Park Avenue penthouse from a Park Avenue address, for the affordable price of a CUNY tuition. Sounds like a good deal.

Across the street from North Building is the Millan House, completed in 1931 with funding from John D. Rockefeller Jr. Stretching the width of the block with an interior courtyard, 116 West 68th Street has an extensive stone menagerie on its façade.

Prior to 1924, the block was the site of Hahnemann Hospital.

Another block to the south on Park Avenue is the historic Seventh Regiment Armory, which is presently used for a variety of public and private events, but best known for its art shows.

Across Park Avenue at 47-49 East 65th Street, Hunter College owns a townhouse which is used for its Public Policy Institute. Formerly the home of Sara Delano Roosevelt, the property was sold by the Roosevelts to the college in 1941 at a reduced price. So not only does Hunter College have Park Avenue penthouse views, it also has its own Upper East Side townhouse. Not bad for a public college.

Returning back to campus, there is a plaque on the wall of the West Building describing the previous property owner, Lexington School for the Deaf. Founded in 1880, it was built in Lenox Hill together with other institutions and it too had a beautiful building that is now a distant memory.

As mentioned earlier, Hunter followed the pattern of many other city nonprofits in gradually following Manhattan’s northward development. City College was founded on 23rd Street and later relocated to Hamilton Heights, its old campus becoming Baruch College. In 1931, Hunter nearly did the same by constructing its Bronx Campus on the shore of Jerome Park Reservoir in the Bronx. Only a portion of the planned campus was completed but the main disciplines remained at Lenox Hill. Instead, the Bronx Campus later spun off into a separate entity, Lehman College. In downtown Brooklyn, its local female division merged CCNY’s Brooklyn men’s division to form the co-ed Brooklyn College in 1930.

Continuing east on East 67th Street, Hunter has another off-campus facility, the Baker Theatre Building, donated to Hunter College by alumna Patty Baker and her husband Jay, the former president of the retailer Kohl’s. The building houses the college’s theater program. Its name was unveiled on January 22, 2016, the college’s newest property. Prior to this, it was owned by the Catholic Church and used as a school.

Hunter College has three other off-campus units. Its highly selective high school is located further uptown on East 94th Street, at the former Squardon A Armory. Its social work school is in East Harlem, while its nursing school and residences are located next to Bellevue Hospital.

The block of East 67th Street between Lexington and Third Avenues contains a diversity of architectural styles with plenty of history in each building. To the right of the Baker Theatre is the 19th Precinct station house. A narrow alley next to the police station descends into an underground garage, but with side windows on the station house, it has the appearance of a secret street.

To the right of the police station is FDNY Engine 39/Ladder 16. From 1887 to 1914, this firehouse served as the headquarters of the New York City Fire Department.

To the right of the firehouse is a blend of Moorish and Byzantine revival, the Park East Synagogue. Founded in 1889, the Orthodox congregation is led by Rabbi Arthur Schneier, an outspoken human rights advocate. Over the course of five decades with Rabbi Schneier at the pulpit, the synagogue has hosted popes, presidents, princes, and most recently, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon in February 2016.

The exterior has numerous commemorative plaques, including one for Soviet Jews. A few feet away, the street sign reads “Sakharov-Bonner corner,” honoring Soviet dissidents Andrei Sakharov and his wife Yelena Bonner.

It’s no coincidence as across the street from the synagogue is a heavily fortified apartment building shared by diplomats from Russia and Belarus.

Previously, it was the Soviet Mission to the United Nations. The heavy security was installed in 1981 after followers of Rabbi Meir Kahane’s Jewish Defense League placed firebombs at the building in a campaign to free Soviet Jews by any means necessary. In February 1987, the recently released dissident Natan Scharansky stood outside this building in a peaceful protest while his newborn daughter Rachel was cared for at the Park East Synagogue. The world’s biggest country also has a consulate on East 91st Street and a residential tower for its diplomats in Riverdale.

Turning back to East 68th Street, there is a small park used by students and sometimes open to the public. Named Poses Park after a college official, it is graced by Giuseppe Massari’s sculpture Mother Italy. Created in 1953, it was donated by the D’Agosto family and installed at the park in 2000.

An ideal place to end a tour is where it began, at the subway station. Looking up are the sky walks of Hunter College. It’s the only set of enclosed pedestrian bridges where one bridge is constructed directly above another. If you haven’t had enough Hunter College history, visit the Hunter College Archives Flickr account.

For the last decade of his life, my father Anatoliy Kadinsky (1960-2014) worked at the home of the Hawks as its Associate Director of Research. An example of immigrant success, the former mechanical engineer retrained himself as a computer programmer, mastering new programs and codes as they were introduced. It was an inspiration to see the middle-aged man working alongside much younger technical talent, demonstrating how far knowledge can take a person.

Sergey Kadinsky’s new book, Hidden Waters of New York City, is now available for pre-order.

2/14/16