In January 2018 I had the opportunity to tour the grounds of the former St. Charles Seminary in Todt Hill, Staten Island, which incorporates the Ernest Flagg Estate and its historic buildings, which I’ll get to later. Through the magic of Zuckerberg, I have been reconnected with some former high school mates including Brian Zuar, a classmate at Cathedral Prep from 1971-1975. This was a Brooklyn high school for boys who had an inkling that they may want to be priests, and was a Catholic school with regular celebrations of the Mass, visits to St. James Cathedral on Jay Street, and trips to retreat houses such as the long-gone Augustinian Academy on Grymes Hill. However, religion was never laid on really thick — boys who continued to have a vocation continued on to seminaries in Douglaston and elsewhere. Personally, though I have respect for the Church, I was never serious about a vocation; what attracted my parents and me was the offered scholarship based on my good marks in grade school, which meant I attended high school free of charge (which I also could have done had I attended a public high school but we felt that a Catholic high school was better educational quality overall).

Other than a class reunion or two I had not spoken to Brian for almost 43 years except for Facebook messages, but when I met up with him at the Avenue M Q train station near his home, we picked up where we left off and swapped stores about the school, still-living classmates and those who had passed on. The purpose of our meeting was that I had heard that St. Charles Seminary, which has occupied the Flagg Estate since 1948, was up for sale and many of its buildings would be torn down. I had remarked about it on Facebook, and Brian offered to tour me around the old place, as he is a former resident and has kept in touch with the longtime groundskeeper.

The Dead Hill

You will not find the word “todt” in the modern Dutch dictionary, not at least in the context of “dead” or “death.” The modern Dutch words are different. Yet, “Todt Hill” is most often said to mean “dead hill” or “death hill” using a regional or archaic Dutch term, and the most likely story is that the hill itself is named for 113-acre Moravian Cemetery at the bottom of the hill at Richmond Road. However, the road can be found as “toad hill” on some old maps, which is likely merely an English bowdlerization. Frogs probably did proliferate in the area, which was once shot through with creeks and rivulets.

Todt Hill did not always bear that name. From the Dutch Colonial era to the end of the American Revolution the area, which incorporates the large wedge of territory north of Richmond Road and east of Todt Hill Road, was called Yserberg (roughly “Iron Mount”) because large deposits of iron were found in the ground, and substantial iron mining activity followed. In the 1800s, longtime landholders the Dongan family granted Warmaldus Cooper the rights to mine the territory at the crest of Todt Hill near Ocean Terrace. The serpentine rock in the area (so called because its striations resemble snakes) contained numerous iron deposits. By 1881 more substantial deposits were found elsewhere, and since much of the iron ore had been extracted, mining ended. However, streets such as Iron Mine Drive, Cooperleaf Terrace and Cooperflagg Lane attest to its history.

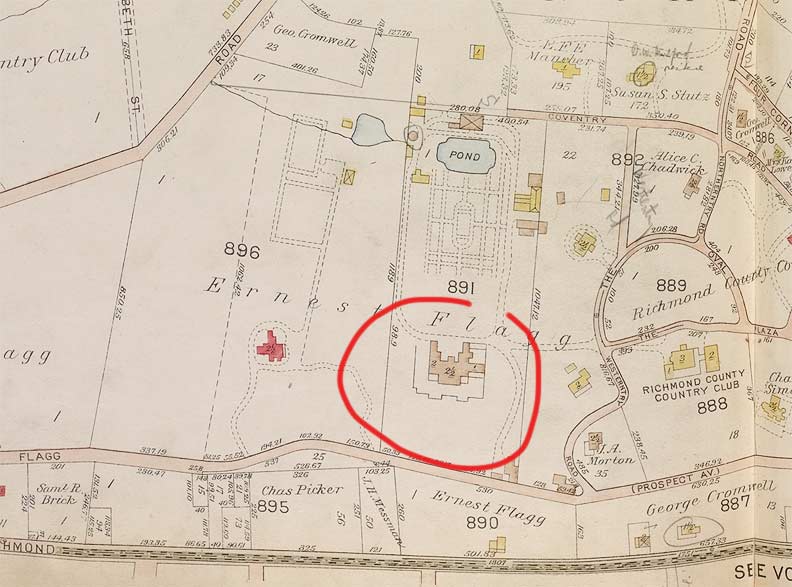

A 1917 map of southwestern Todt Hill is remarkably similar to today’s layout. The Richmond County Country Club, and its unique street plan, are still in place today, although roads curiously called “Westerntry” and “Northerntry” have dropped that extra “r.” I’ve seen it that way in street guides, too, so it may not be a misprint.

At the upper left, the George Cromwell estate belonged to Staten Island’s first borough president. Richmond County became a part of NYC in 1898.

The Flagg Estate is just to the west, along Flagg Place, formerly Prospect Avenue; it runs along a high ridge above Richmond Road. I have circled the mansion I visited. The grounds originally had a pond, which later became a swimming pool and is now a sculptured lawn. To the estate’s west, suburban housing built by Robert A.M. Stern was constructed in the 1980s along new streets bearing names like “Cooperleaf” and “Cooperflagg.”

Ernest Flagg

Ernest Flagg (1857-1947) was one of NYC’s most prolific architects. Among his creations were the Singer Tower, above, at Broadway and Liberty Street (above) in lower Manhattan (1908-1967), the tallest building to ever be deliberately demolished not as part of a terrorist attack; the Cherokee Apartments on the Upper East Side; Charles Scribner’s Sons Building on 5th Avenue; as well as the expansive Flagg Court complex on Ridge Boulevard in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. Flagg once believed that Staten Island would become NYC’s premiere borough (he was hardly prescient about that) but it prompted him to build his huge estate, Stone Court and Cooperflagg Estates (remembering the name of the land’s original iron miner), on the scarp separating Todt Hill from the neighborhoods below it along Richmond Road. Many of the buildings are now landmarked, while others are part of St. Charles Seminary.

Flagg Court, 7200 Ridge Boulevard in Bay Ridge. Currently FNY headquarters is in Westmoreland Gardens in Little Neck, a complex I had my eye on beginning in the 1990s when I lived in Flushing. I finally got my opportunity to buy a co-op there in 2007. Before that, when I lived in Bay Ridge, I eyed Flagg Court for years but didn’t get in. It was designed by Ernest Flagg and constructed between 1933-1936.

This 422-unit, six-building complex contained architectural features that were avant-garde for its time, including reversible fans below the windows and exterior window shades, both now removed, as well as innovative uses of concrete as finished ceilings and for a vaulted auditorium. Its most pronounced exterior feature is the pendant Carpenter Gothic cornice at the eighth floor. The complex was socially innovative, as well, as it included a tea room, auditorium, swimming pool, bowling alley, tennis and handball courts, and a nursery school to allow the building’s mothers three hours of daily free time. [Historic Districts Council]

The Flagg Estate/seminary grounds are approached through a stone gateway on Flagg Place. Just past the gateway is a Landmarked building called Bowcot (seen better on Street View). Ernest Flagg was a skyscraper builder, but he also designed hundreds of small-in-stature dwellings and cottages including this one. Along with the gate, it is constructed with a technique called “mosaic rubble” which involves setting rubble stone into a concrete wall. “Bowcot” is a contraction of “bowed cottage.”

Before going into the grounds, have an overhead look on Street View — it’s spectacular.

This is actually the rear of the Ernest Flagg mansion, Stone Court — the front was in the shade, so I thought this would be a better shot. A two-tiered porch looks down a huge lawn on a steep incline and the neighborhoods of Dongan Hills and Todt Hill are spread out before you, with Raritan Bay in the distance.

After Ernest Flagg visited Todt Hill in 1897, he purchased land and built a stone mansion whose design was based on early Dutch Colonial dwellings with steep, pitched roofs and deep eaves. When the mansion was renovated and enlarged in 1908 that roof was largely hidden behind the porches — it can be made out better in the overhead Street View shot. Flagg also built a plethora of other buildings on the grounds, to be seen further down the page.

Center for Migration Studies building, part of St. Charles Seminary

Saint Charles Seminary entered the picture in 1948 when the Society of St. Charles-Scalabrinians, an institute of Roman Catholic priests and brothers founded by Giovanni Batista Scalabrini (1839-1905) in 1887 to provide pastoral care and religious advice to Italian immigrants, purchased the estate from Ernest Flagg’s widow, Margaret Elizabeth Flagg, for $65,000. The Scalabrinians employed the grounds as seminary for several decades and in 1964, established the Center for Migration Studies to collect and disseminate information on population migration.

In early 2018, local developer Tom Costa was awaiting approval to purchase the seminary grounds for $10M. Though Stone Court, which is landmarked, would be retained and renovated for an additional $7M, other more recent buildings such as the CMS building would be razed. None of the original buildings designed by Ernest Flagg are endangered, but it’s the end of an era nonetheless. Condominiums would take the place of the razed buildings.

What follows is a set of photos I took of the interiors of the mansion and its newer satellite buildings that are connected by underground passageways — guided by Joe, the groundskeeper, we never needed to emerge into the cold to go between buildings. Joe is also an amateur vintner; he has a still in the basement, and supplied Brian with samples, which we sipped on for part of the ramble.

The chapel is on a wing near the mansion entrance.

Looking toward the living area. The deep-focus reminded me of a Welles or Kubrick shot.

From inside the back porch, looking out toward Raritan Bay and the NJ Highlands.

In 2001, I had a dream that I was hiking and saw the Verrazano Bridge towers, one in front of the other. Soon after, I hiked on Flagg Place, not aware that just such a view was available from there. Quite strange.

A look at Stone Court from the lawn.

Some rooms had been untouched for awhile. A phone book, a hammer, and stacks on MOR records including the Lettermen, Nat King Cole and Lawrence Welk were encountered. The Lettermen were a pop vocal trio who rang up hits between 1960 and 1971; their biggest hit was a medley, “Goin’ Out of My Head / Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” in 1967. They continued to record through the 1980s; I wonder if they ever appeared on any of David Letterman’s shows.

Now in the kitchen of the Center for Migration Studies building, slated for demolition.

Photos from the history of St. Charles, from what appears to be the 1960s and 1970s.

The purpose of this device stumped me. If you have any ideas, let me know in Comments.

I couldn’t resist.

Some time has passed since the gas was turned on.

The workshop of the CMS building incorporates a former swimming pool.

For no discernible reason in my youth I was a missal collector (I enjoyed the typography). I found one here at St. Charles with the classic arrangement of Latin on the verso, English on the recto. However, liturgical Latin is as far away from classical Latin as the English of Chaucer is from the English of today. Classical Latin was in all caps and barely punctuated, and liturgical was pronounced differently: Veni, vidi, vici in Classical was weni, widi, wikki, while Liturgical was vayni, veedee, veechee.

In the Bible, Zachary was the father of John the Baptist, and there has been a President Zachary, and one of my favorite TV characters, Lost in Space‘s devious yet cowardly Zachary Smith (more recently, Zachary Smith is a popular comedian on the Instagram platform).

Back in the mansion again, we walked into what appeared to have been a ballroom.

The upstairs bedrooms doubled as quarters for priest and seminarians after 1948. They have a view of the lowlands and Raritan Bay.

As always I was fascinated by the ceiling lamp sconces.

A portrait of Albino Luciani (1912-1978) who served as Pope John Paul I between August 26 and his death on September 28, 1978. Known as the “smiling Pope” because his sunny demeanor contrasted with the severe one of his predecessor, Pope Paul VI, his Papacy was the shortest in history. Conspiracy theorists still maintain he was assassinated but no definitive evidence for this has ever been recovered. The late Fall frontman Mark E. Smith disagreed and wrote a pop song, “Hey! Luciani” about him.

A walk through empty rooms.

Educational materials about the Society of St. Charles-Scalabrinians have been on the desk since at least 2010. The grounds are still maintained well, and there was no hint of dust and cobwebs.

From the widow’s walk above the second floor porch, we were fortunate to see the lowlands, the bay and the NJ Highlands on this severely clear day (in the cold months, such days are a rarity).

A view from the north side. The hills in the background are among the highest on the East Coast.

Another Latin-English missal. I was told that they were free for the taking, but I was without my knapsack, and had no way to spirit them home conveniently. From the looks of the typography, this was an edition by St. Joseph, published by the Catholic Book Publishing Corporation, which is still in business, producing daily and Sunday missals. They also printed the large missals you see priests using during Mass and this was likely one used until Latin was eliminated from daily Mass celebrations in 1969. However, the Latin, or Tridentine, Mass is still popular and is celebrated widely.

Joe, Brian and I drove to the rear of the property and its array of Flagg-designed stone cottages, which likely housed the estate employees.

The largest of these is the carriage house. Remember, the Ernest Flagg designed ancillary buildings on the site are safe from demolition.

The carriage house looks out over a vast lawn. There was originally a pond here and later, a swimming pool.

During my visit, the fieldstone water tower was in shadow, so I am using a Street View photo here. According to Virginia Sherry at SILive, the tower once had a conical roof topped by a small windmill. Reporter Sherry had lived in an Ernest Flagg-designed cottage that still stands on Richmond Road.

After pizza for lunch on New Dorp Lane (the diner I had in mind was closed, and I was unaware of the nearby presence of the nearby Colonnade Diner on Hylan Boulevard) it was time to kick it in the head for that day, and Brian deposited me at the 95th Street R train after a ride over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

From You’d Never Believe You’re in NYC, reality hits you like a wet washcloth once you’re back in the train. However I always find fascinating items there, and there are several at 95th Street, such as this decades-old track indicator…

… worn mosaic signage….

A signal box from General Railway Signal Co. of Rochester, NY, in business from 1904-1998 when it merged with Alstom Transport of France.

Only the R, F and A lines currently use the R-46 species of subway cars, first introduced with carpeting (some R44s had carpeting; see Comments) in the mid-1970s. It was also the first subway car to use the familiar “bing-bong” sound effect when the doors were closing. After initial problems such as cracks in the undercarriages, the R-46s have been durable. They are in line to be replaced by newer cars over the next decade after almost 50 years on the tracks.

Thanks to Brian Zuar, Cathedral Prep ’75, and Joe, the longtime Flagg Estate groundskeeper, for this unique tour.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

3/4/18