Prospect Park South was developed at the turn of the 19th-20th Century by upstate New Yorker Dean Alvord, who purchased a parcel of land in Flatbush from the estate of Luther Voorhies and the Dutch Reformed Church in 1898. Alvord, with the aid of architect John Petit, set about building sumptuously-appointed buildings for the well-to-do. By 1898 Flatbush had evolved from farmland into a well-established community that boasted good schools, decent local trolley lines, and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, the precursor of the BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) offered easy transport to Manhattan via the Brooklyn Bridge on what was once a steam line called the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Brighton Beach Railroad that evolved into today’s B/Q train.

Alvord’s idea was to extend Prospect Park South and adapt it to residential use. He foresightedly buried utility lines underground (other Brooklyn neighborhoods are marred by overhead utility wires) and paved the streets in an age when many were still dirt roads or Belgian-bricked. Streets were given British-sounding names. Grand houses of every description appeared: neo-Tudors, French Revival, Queen Annes, Italian villas, Colonial Revivals, Mission styles, and houses designed to individualistic styles and bearing no relation to previous forms. Undoubtedly, many of the houses bear a resemblance to the grand southern plantation mansions.

I was recently on my way to a birthday dinner that friends in Prospect Park South have for friends whose birthdays are in late August. Unfortunately, I had arrived a day early! The day wasn’t a total loss as I wandered around Prospect Park South first with the camera. I could have walked down the center of Cortelyou Road with impunity, as there was a street festival that day. I decided instead to concentrate on Buckingham Road, which is somewhat unique in Prospect Park South, which has a designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and adjacent Caton Park, which does not. Prospect Park South runs from Church Avenue south to Beverl(e)y Road, and from Stratford Road east to the BMT Subway (B, Q) open cut, while Caton Park runs between Caton and Church Avenues from Stratford east to East 17th.

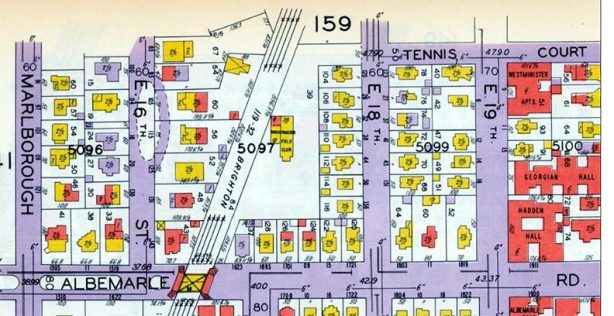

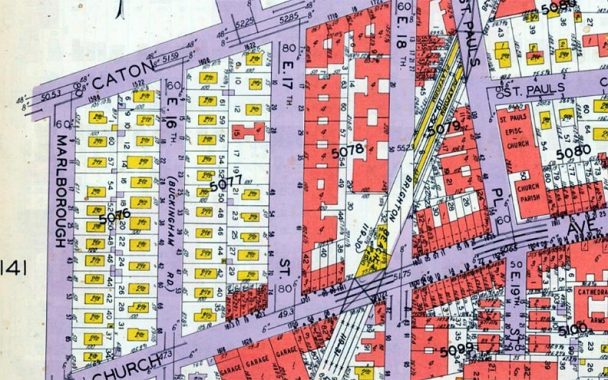

Unlike the other “British” named streets of Prospect Park South — which were originally East 11th-17th but were renamed by Alvord — Buckingham Road’s name has always been somewhat unofficial and the street is marked as both East 16th Street and as Buckingham Road. This 1929 Belcher Hyde map shows the southern end of Buckingham Road, the part that is within the PPS Landmarked district, as just East 16th Street…

…while the northern section between Caton and Church, in un-landmarked Caton Park, is shown as East 16th but with Buckingham Road in parenthesis.

Today, the Department of Transportation effects a compromise. The landmarked section is strictly “Buckingham Road” on the maroon signs used in landmarked districts, while a second “Buckingham Road” sign is affixed next to the East 16th Street sign, almost sheepishly, at Caton Avenue.

In 1900 Brooklyn Rapid Transit acquired many of the surface steam railroads in Brooklyn and set about converting them to mass, “rapid” transit to serve the growing NYC borough. Among the acquisitions was the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railroad, which ran from Fulton Street to Coney Island. Over time, the northern section became the Franklin Avenue Shuttle and the southern part became the BMT Brighton Line (the BRT reorganized into the BMT after the Malbone Street Wreck in 1918).

Two stations on the Brighton, Beverl(e)y and Cortelyou Roads, a block apart, greatly resemble their original appearance from the year they opened, 1907, running in an open cut, with very narrow platforms and a chalet-type station house. 1990s renovations put picture windows in the stations over the tracks and new tiled signage that features the only use of the Times Roman type font in MTA stations.

Painted signs from the Greenfield Chemist (Pharmacy) can still be found on the brick wall overlooking the tracks. The signage emphasizes the soda counter and luncheonette that can no longer be found in the still-existing drugstore.

A look at the present-day Greenfield Pharmacy, on the corner of Cortelyou and East 16th.

A look at the same corner in 1940, But where’s the pharmacy? the corner is occupied by Roulston’s, a chain of groceries in the metropolitan area founded by Thomas Roulston, an Irish immigrant to NYC, in 1888. The chain folded in 1951.

A couple of doors down, you can see the Greenfield pharmacy in the center, marked by a neon sign advertising drugs, soda; with “prescriptions” and “Luncheonette” on sidewalk-facing glass signs. “The Greenfield Pharmacy” sign is partially hidden behind the neon sign.

Many liquor stores are not titled at all, with just the word “liquors” in plastic or neon letters above the entrance. Some liquor stores have not changed their signage in decades.

#284 East 17th, between Cortelyou and Beverley, is not in the Prospect Park South landmarked district, but these streets have their moments, like this Queen Anne style house with a circular corner tower, dormer window, and wide-open porch. Two prime spots to sit and watch the passing parade, in the tower when it’s cold, on the porch when it’s warm.

143 Buckingham Road at Albemarle Road is a rare all-brick house in Prospect Park South, designed in 1906 and combines Italian villa and Colonial Revival. The corner cupola overlooks the Brighton Line subway.

Prospect Park South’s famed Japanese house (admittedly, best viewed in the cold months with little foliage) was designed in 1901 and contains carefully adapted Japanese temple detailing including three stained glass windows with dragon motifs. Japanese artisans were hired to provide expertise on the details. The house originally sold for $26,500 which was quite expensive for 1901. The original owner was Dr. Frederick Kolle, a pioneer in the fields of radiology and plastic surgery and the inventor of a number of X-ray devices.

Unusually, Buckingham Road was designed with an oval-shaped center median between Albemarle Road and Church Avenue. It’s one-way going north, so a motorist has their choice which one to take. As Yogi Berra said, when you come to a fork in the road, take it.

At #125 Buckingham, this classic temple-style house with 4 massive Corinthian columns in front was built from 1910-1911 for George Urban Tompers, a specialist in reorganizing companies that had fallen on hard times.

#115 Buckingham is a Shingle Style gambrel (angled) roof house built in 1900. Unfortunately its large corner tower is invisible behind foliage. Shingle-Style houses are most popular in New England coastline villages. It was designed by John Petit and built in 1900.

The largest building on Buckingham Road is a large apartment complex built in 1937 at #105. It extends all the way back to the Brighton Line tracks, which are angling northeast, giving the plot plenty of space.

Across the street, #116 is another eclectically constructed Queen Anne building. It was finished in 1914 and was designed by Slee & Bryson, an architectural firm responsible for many designs in Prospect Park South and Ditmas Park, the district to its south.

#104 Buckingham was built in 1901 by architect Carroll Pratt. Note the two massive Ionic columns (one is in disrepair) and two Ionic pilasters, or half columns set into the wall.

#85 Buckingham is a tidy Dutch Colonial building featuring another gambrel roof, Palladian window on the 2nd floor, and porch supported by four massive Doric columns.

Buckingham Road contains what’s likely the heaviest concentration of post-Victorian architecture, but there’s more on Marlborough Road one bloc k to the west, and scattered along many of the other British-sounding street-named blocks.

Prospect Park South features its own gatepost designs marking what was once a semi-private district. New York City has never really settled on a spelling for Brooklyn’s Beverl(e)y Road, which appears on street signs with and without the E; The BMT’s Beverley Road station has the E, while the IRT station a few miles east doesn’t. The PPS gateposts spell it Beverly.

For Buckingham Road, the carvers used what I call the V of Importance, imitating classical stonecarvers who worked in an era when U and V were the same letter. They made their U’s come to a point, because that was easier to carve. It was only much later that the two letters came to represent different sounds and were individualized.

Prospect Park South also had iron street signs. A few of the rusted iron stanchions can still be found, but this one, on Marlborough and Albermarle, is the only one still with a sign.

And lastly, adjacent to the iron sign is this concrete post, with pebbled stonework. What can it be? It formerly held a very small slotted mailbox, where only letters can fit. The Post Office, fearing bombs, has returned to clot-only mailboxes, but has retained their former boxy signs, so the small boxes aren’t coming back.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

8/18/19