It had been quite a while since I walked Hudson River Park at the southwest end of Manhattan. In fact it had not been since November 2011, when I led FNY Tour #50 there from the Battery all the way to the Intrepid at 46th Street. FNY Tours, in non-Covid times, have become somewhat less ambitious and I do shorter routes these days. Today, by myself, my aim was to get from Chambers Street at Stuyvesant High School all the way to 34th Street and catch the #7 train back to Queens. I almost made it but had to cut it short for reasons described later.

In December the shadows can be harsh. And this was a clear, fairly cold day with the weather around freezing.

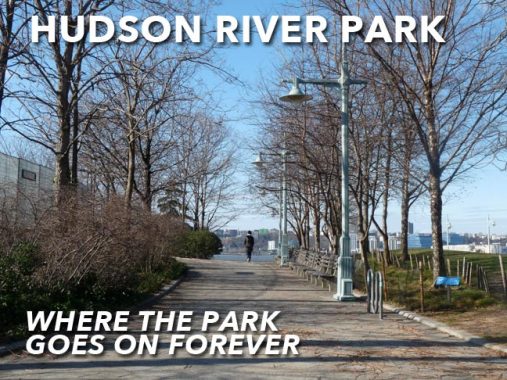

Hudson River Park runs from here north to 72nd Street, where it changes names to Riverside Park. Together, the two parks comprise Manhattan’s second-biggest park, following you know what. Hudson River Park arose as city and state officials tried the West Side Highway after its collapse in 1973 that forced its closure.

From 1937-1973, West Street and 11th and 12th Avenues were covered by the elevated West Side Highway, which served as a barrier to the riverside docks. The highway was unusual, with mid-span entrances and exits, Belgian block surfaces, and tight turns. The span was closed from the Battery to 18th after a dump truck collapsed the roadway, which was in deferred maintenance for many years. Other sections were subsequently closed and the elevated was demolished in the early 1980s.

A replacement which would involve a waterside highway with parkland, called “Westway” was opposed by environmental groups and criticized as a boondoggle by elected officials. Judge Thomas Griesa eventually blocked a permit to build the road because it was successfully argued that the road would harm the breeding areas for striped bass. Between 1985-2001 the present surface highway, officially known as the Joe DiMaggio Highway, was completed, and Hudson River Park was then developed along the waterfront. Hudson River Park is a work in progress, and additions are being constructed to this day.

A sloop sits in the Hudson River just above the Chambers Street landing where Frederick Douglass landed in NYC after escaping slavery.

On September 3, 1838, Frederick Douglass successfully escaped slavemaster William Freeland by boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. He was dressed in a sailor‘s uniform and carried identification papers which he had obtained from a free black seaman. He crossed the Susquehanna River by ferry at Havre de Grace, then continued by train to Wilmington, Delaware. From there he went by steamboat to “Quaker City” (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and continued to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York; the whole journey took less than 24 hours. wikipedia

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) later wrote of his arrival in New York:

“I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the ‘quick round of blood,’ I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: ‘I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.’ Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.”

Lilac is a 1933 former lighthouse tender moored at Pier 25 at North Moore Street that brought supplies to lighthouses and maintained buoys for the U.S. Lighthouse Service and the U.S. Coast Guard. Decommissioned in 1972, Lilac is now owned by the non-profit Lilac Preservation Project. Lilac is the oldest lighthouse tender in America and the only steam-powered tender to survive with her steam engines intact. Lilac is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and eligible to become a National Historic Landmark.

At Pier 34 are a pair of bridges, one a pedestrian bridge that was locked today but is open, I presume, in better weather, and a vehicular bridge leading to the Holland Tunnel ventilation shafts that ensure that the tunnel has breathable air by eliminating carbon dioxide and auto exhaust.

Holland Tunnel engineer Ole Singstad (who replaced original tunnel engineer Clifford Milburn Holland) is little remembered today but should be mentioned in the same breath as Robert Moses and Othmar Ammann. He designed or consulted on all of NYC’s major vehicular tunnels: the Holland, Lincoln, Queens-Midtown and Brooklyn-Battery, and other major tunnels in Baltimore, New Jersey, Boston and Oakland. Singstad regretted that his tunnels were mainly used for autos and not for mass transit. The Holland, featuring Singstad’s novel ventilation system, opened in November 1927.

Compared to locales like London, UK or Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia, New York City is rather staid, architecturally speaking, but there are some modern gems to be found along Hudson River Park and the routes that border it, such as this Department of Sanitation salt shed at West and Spring Streets. It’s part of DSNY’s gi-normous complex and by far is its most novel element. Designed by Dattner Architects with WXY Architecture + Urban Design and opened in 2016, it’s supposed to be reminiscent of a very large salt grain. It can store 5000 tons of salt, in a region that can have as much as 6 feet or snow or less than 6 inches over the course of a winter.

Pier 40 has become an important recreational facility in park-poor southwest Manhattan, with batting cages, driving ranges, kayaking, trapeze, football, rugby and more. It was expanded to its current size in 1962 when it was home to the Holland America shipping line. Even after Holland America moved out, the pier continued to be used as a shipping terminal until 1983. It became part of NYC parks in 2005.

On the south side of the building was a painted tribute to NYC’s “first responders,” nurses, doctors and medical personnel, in the 2020 year of Covid.

Outside the pier, you can find some of NYC’s rustiest lampposts. The DOT doesn’t bother repainting lampposts after a sufficient amount of rust.

Undulating, curved exteriors are a trend in architecture, and can be seen here at #357 West Street at Clarkson, opened in 2019 and designed by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron. The condo complex was developed by Ian Schrager, who turned his attention to real estate after his Studio 54 days.

Previously, the site was partially occupied by the tiny Terminal Diner, which was known as The Rib before its closure in 2006. You can see more long-gone bits of West Street on this FNY page written in 2007.

375 Hudson Street, home of the Saatchi and Saatchi global ad agency at Hudson and West Houston, with its hundreds of windows wrapping around curved edges, echoes the earlier Starrett-Lehigh Building further uptown.

The remains of Pier 42 at Morton Street can be seen here. A ferry to Hoboken used to run from Pier 43. You can see the city in the rear including the Erie Lackawanna terminal clock tower at left. I worked at 211 River, in the center, for 9 months in 2016. I alternately spend a lot of time in Hoboken or none at all; in the 1980s, I was a devotee of the Pier Platters records store where I would obtain tickets to shows at Maxwells, named for the old Maxwell House coffee factory in town.

Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra‘s fascinating overlapping portraits of Michael Jackson, David Bowie, Andy Warhol, Frida Kahlo, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat can be seen all over town, in Jersey City and other locales. This “Stop Wars” wall on West between Christopher and West 10th was his first NYC “installation.”

Pier 45, the Christopher Street Pier, was rebuilt several years ago, removing its rough and ready image. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1990s, it was a big part of the local Village gay social scene. Signage proclaims it as prime spot for sunbathing, which I don’t recall seeing on any other other signs around town.

The Apple, located near Pier 45, is a 3-ton bronze sculpture created by Stephan Weiss, co-founder of the Urban Zen Foundation and the late husband of fashion designer Donna Karan. Weiss died from lung cancer in 2001. It’s reminiscent somewhat of the famed Sphere sculpture at the World Trade Center.

Once the lane that ran along the north side of the old 1797 State Penitentiary (moved to Ossining in 1829 and nicknamed “Sing Sing”) Charles Lane now runs between the twin towers comprising Richard Meier’s glass-faced Perry Street exclusive condominium development. Here’s a look inside one of the apartments, which rented at $60,000 a month in 2017.

Charles Lane (1905-2007) was also a busy character actor who appeared in over 300 films and TV shows between 1931 and 2006, usually playing dyspeptic or annoyed bank clerks, judges, professors or clergymen.

Beginning in the 2000s, Hudson River Park was the first place the NYC Department of Transportation installed retro versions of Triborough Bridge lampposts. They appear here in both single and twin versions. Since that time, the design has also turned up in several locations in Bronx and Queens, painted silver or black.

The remains of Pier 48, at West 11th Street. The pier structure burned down in 1976 from a suspected arson. The pier was used until the 1950s by the Erie Lackawanna Railroad.

Three Forty Three is a Fire Department of New York fireboat commissioned on September 10, 2010. At 140 feet in length and weighing 500 tons it is the FDNY’s largest fireboat, and can pump 50,000 gallons of water per minute. It was named for the 343 FDNY personnel killed on duty on 9/11/01 and serves FDNY Marine Company 1.

Only the tag ends of Gansevoort and Bloomfield Streets, jutting into the Hudson River on landfill, betray the existence of the former West Washington Market, which occupied this site from 1884-1954.

The West Washington Market was enclosed in ten two-story-tall red brick and terra cotta buildings, completed in 1889, set on four streets and one avenue. In 1939, the WPA Guide to New York City described the scene at both the Gansevoort Farmer’s Market and the West Washington Market:

“Gansevoort Market, or ‘Farmers’ Market,’ as it is generally known, occupies the block between Gansevoort and Little West Twelfth streets. Farmers from Long Island, Staten Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut bring their produce here at night for sale under supervision of the Department of Public Markets. Activities begin at 4 a.m. Farmers in overalls and mud-caked shoes stand in trucks, shouting their wares. Commission merchants, pushcart vendors, and restaurant buyers trudge warily from one stand to another, digging arms into baskets of fruits or vegetables to ascertain quality. Trucks move continually in and out among the piled crates of tomatoes, beans, cabbages, lettuce, and other greens in the street. Hungry derelicts wander about in the hope of picking up a stray vegetable dropped from some truck, while patient nuns wait to receive leftover, unsalable goods for distribution among the destitute. The market closes at 10 a.m. and is not open Sundays or holidays. Across West Street is the West Washington market, comprising ten quaint red brick buildings which house a live poultry market patronized mostly by kosher butchers Since poultry requires ample heat in winter, every stall is equipped with a furnace, so that each roof adds more than a dozen chimneys to its picturesque architecture.” [Village Preservation]

West Washington Market had a street system independent from the rest of Manhattan except for the presence of 13th Avenue, which remains in place at its west end. The only current tenant is FDNY Marine Company 1, which boasts one of the newest FDNY firehouses, commissioned in 2010.

Plans call for a new public space, the Gansevoort Peninsula, to be built on the man-made feature that will be mix of recreational and more natural parkland. The FDNY marine company will be retained as will 13th Avenue. In 2020 the only hint that new construction will begin is a set of new LED lampposts.

Two of the newer and more avant-garde buildings in what had been NYC’s Meatpacking District. On the left is Standard New York, the latest hotel in a chain by hotelier André Balazs, straddling High Line Park along Washington Street between Little West 12th and West 13th Streets.

On the right is the new home of the Whitney Museum of Modern Art. The museum evolved out of the personal art collection of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a member of two of NYC’s wealthiest and historic families. The Museum was founded in 1931 on West 8th Street, moved to West 54th Street in 1954, to Madison Avenue and East 75th in 1966, and finally to their new glassy, cantilevered headquarters on Gansevoort between West and Washington designed by Renzo Piano, also the architect behind the new New York Times building and new buildings in the Columbia University Manhattanville campus.

According to the Museum’s website, “The Whitney’s collection includes over 21,000 works created by more than 3,000 artists in the United States during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. At its core are Museum founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s personal holdings, totaling some 600 works when the Museum opened in 1931.”

This gate, at the head of what was Pier 54, is the last remnant of a terminal building for White Star ocean liners. Having been preserved by serendipity, it’s now part of Hudson River Park. One of the spectacular ocean liners that used this gate in their heyday would have been the Titanic, though he great liner was due to arrive at nearby Pier 58 — if fate had not intervened. It was there that passengers from the doomed vessel debarked after they were picked up in the icy North Atlantic Ocean by the Carpathia, operated by Cunard.

This is where the RMS Lusitania, the fastest, one of the most luxurious, and second largest liner in the world departed on its final voyage. On May 1st 1915, 1900 people departed Pier 54 for a voyage that would be implanted in the memory of folks for years to come. On the 7th of May, the Lusitania was torpedoed by a German U-boat, sinking in 18 minutes, and taking 1200 victims down with it.

Most of Pier 54 has been demolished, and a new island park, Little Island, is under construction. The park will not be officially part of Hudson River Park; instead, it is being privately funded and built by media mogul Barry Diller and his wife, fashion designer Diane Von Furstenberg. The park is constructed on 132 golf tee-shaped pylons sunk into the Hudson River bed. The park will contain nature trails, hills, and a 700-seat amphitheater. The park’s design is by Thomas Heatherwick, who also designed “The Vessel,” the climbing structure in Hudson Yards further north. The island park is scheduled to open in the spring of 2021.

Though the Meatpacking has seen its share of novel retail and residential construction, rather staid and standard-issue glassy office towers such as 860 Washington Street at West 13th Street have also arrived.

Pier 57 is a handsome steel and masonry structure at 10th Avenue and West 15th Street, constructed from 1950-54 as a headhouse for shipping lines. The structure is supported on three T-shaped caissons in the Hudson River just off the shoreline. The Grace Line was the building’s first tenant, serving as a cargo and shipping terminal. After the shipping line relocated from the building in 1967, it became a bus depot for the Transit Authority, later the MTA, until 2003. It was subsequently a detention center for arrested protestors during the 2004 Republican national convention; many sued and won for damages and injuries received from chemical burns suffered during exposure to asbestos, motor oil and other toxic chemicals.

Recently, the building has been reborn as a retail, offices (to include Google) and concert complex as famed venue City Winery has relocated in the building. A food market was planned by famed gourmet Anthony Bourdain, but was scuttled by Bourdain’s suicide; dining venues are planned.

Since 1954, wall bracket versions of finned “Whitestone” streetlamps have been appended to the building’s exterior. During recent renovations, the brackets received new LED pendant fixtures.

The National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) Building on 10th Avenue between West 15th and 16th where Oreos and Mallomars were invented in 1913 is now home to an engaging indoor marketplace consisting of dozens of vendors, Chelsea Market, and is also home to NY1, NYC’s all-news cable channel.

It can’t be said that I like just “old stuff” which was an accusation I parried at a photo chat I gave some years ago at an Apple Store. There are a pair of truly innovative designs on 11th Avenue and West 18th, across from Hudson River Park, that I do enjoy.

Los Angeles-based architect Frank Gehry’s first major project was the Interactive Media Building completed in 2008, its outline built to resemble a masted sailing ship. Interactive Media president, Barry Diller, and his wife, fashion designer Diana Von Furstenberg, referenced above, each work in the area and have donated large contributions to the High Line project.

Unfortunately the building has been boxed in by high rises recently, and its impact is diminished from everywhere except across 11th Avenue.

Next door, 100 11th Avenue was nicknamed by its architect Jean Nouvel as a “vision machine,” this new expensive condo development features over 1,650 differently-sized opaque glass windows on its exterior. Some of the more expensive apartments are priced at $40 million at least before the Covid crisis.

Colombian muralist Knox Martin‘s “Venus” was painted in 1970 on a women’s penitentiary, the Bayview Correctional Facility, on 11th Avenue and West 19th Street.

Traditionally the goddess of love and fertility, Venus represents woman, erotic and supple, but it also conveys Knox Martin’s love affair with New York. Venus is his love poem to the city where he has always lived, a place that is part of his being. The feminine, curvilinear shapes of the image are in direct contrast with the straight forms that intersect the composition. The overwhelming size of this enormous mural only intensifies the experience of female shapes, the linear aspects of the painted composition, and of the surrounding architecture. In an era when art was reaching out to the masses with pop culture, this huge mural was Knox Martin’s way of touching a public that would never venture into an art gallery. Marilyn Kushner, Brooklyn Museum

The Bayview Correctional Facility was a medium-security federal women’s prison located at 11th Avenue and West 20th. It was built as sailors’ housing in the 1930s and was converted to a prison in the 1970s, with a maximum of 325 prisoners. The last of the inmates were moved out as Hurricane Sandy bore down in October 2012. The future direction of the building is undetermined.

At West 23rd Street and Pier 62, Hudson River Park widens considerably on landfill and I planned to do some exploring here. Unfortunately I suffered a back spasm: my back has developed chronic morning pain since I use an old mattress. I can generally unstiffen my back by walking, but I stood on an incline and twisted my back in an unacceptable fashion. Fortunately it didn’t lock up and after a short rest I was able to walk over to the subway at 11th and West 34th.

The newest neighborhood in Manhattan is promoted as something new where nothing stood before, a blank slate atop a railyard that awaited development. The $55 billion Hudson Yards neighborhood opened in March 2019 with a six block park and boulevard, a privately-operated public square with a sculpture, million-square-foot retail center, performance space, offices, and residences, connected to the rest of the city by the 7 subway line extension.

Sergey Kadinsky: Hidden Hudson Yards

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

12/31/20