By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten New York correspondent

THE flaw of urban planning in Brooklyn is the beauty of Prospect Park as the borough’s signature greenspace, and seemingly endless blocks of housing with few parks to serve the residents. Seeking to correct the absence of public space in neighborhoods distant from Prospect Park, in the 1890s, Brooklyn’s leaders designated a set of park blocks such as Saratoga Park in Bed-Stuy, McGolrick Park in Greenpoint, and Bedford Park in Crown Heights, among others. The Brooklyn Parks commissioner at that time was George V. Brower, whose name was later bestowed on Bedford Park. It is a welcome space of nature amidst the brownstones and apartment buildings.

What makes Brower Park unusual is that it does not occupy its full superblock, with portions of the space given to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum and P.S. 289. The park has active and passive recreational features, but the unique elements are its art and architecture.

The northwest corner of Brower Park contains the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, which stands out with its yellow facade designed by Rafael Viñoly in a 2007 expansion. It gives the museum a new look when it is actually the oldest children’s museum in the country.

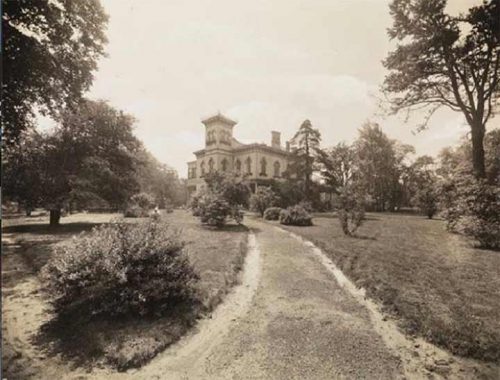

The current facility is the third home for the museum. Its first was in 1899, in the former mansion of William Newton Adams, across the street from this park. Two decades later it moved into another mansion near the park and finally in 1977 it received a modern facility with its signature tunnel leading into two underground levels of exhibits. With the Vinoly expansion, the museum has additional ground-level space and public access to its rooftop.

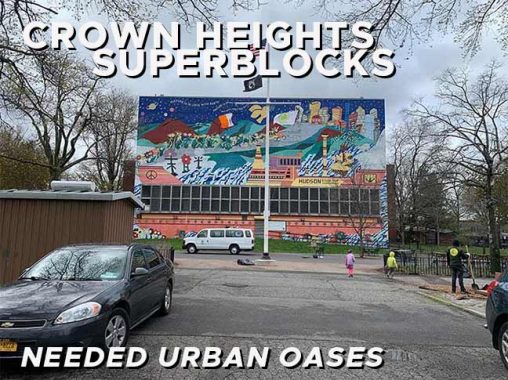

The comfort station is the oldest structure in the park, dating to 1905 with its pediment carrying the NYC Parks leaf logo. The mural in the background frames the park’s border but it is across Brooklyn Avenue, hosted by the Alternative Learning Center.

Prior to 1958, Prospect Place ran through the park, separating the older southern block from the block containing the museum, which the city acquired in piecemeal fashion between 1923 and 1947. That’s how one block of parkland became a superblock. As the need for more classrooms grew, the northeast corner of the park was given to Public School 289, which is co-named for Brower. It is a rare example of parkland reassigned to a school. Another such example is in Morningside Park, and more recently in Flushing Meadows.

Titled Piece Out, Peace In, this mural was organized by the nonprofit Groundswell and designed by artist Joe Matunis with a message against gun violence. The mural shows how easy it is to obtain guns in other states, transport them to New York, and their use in the murder of young city residents.

In the aftermath of the Crown Heights Riots of 1992, efforts have been made to bridge the cultural gap between the Chabad hasidim and Afro-Caribbean neighborhood residents. One such example is the One Crown Heights mural inside the park. In a nod to contemporary problems, this Groundswell mural has a man in a suit with a dollar sign on his eye to depict the gentrification that is displacing longtime renters in Crown Heights.

Across from the southeast corner of Brower Park is the former Shaari Zedek (Gates of Righteousness) synagogue, completed in 1925 on the site of Brower’s mansion. Designed for a wealthy community, this classical revival structure included classrooms, a gymnasium, bowling alley, auditorium, and a pipe organ. At its dedication, its lights were turned on remotely by President Calvin Coolidge from Washington. With white flight in the 1960s and an uptick in crime, the congregation declined. In 1969 it was sold to an African-American congregation, the First Church of God in Christ of Brooklyn. Whatever happens in demographics, the building and its surrounding blocks are landmarked, securing its future on the streetscape.

A block to the east of Brower Park is a miniature park that contributes to its own superblock. Nearly a half century before the DOT implemented the car-free Open Streets program, a block of St. Mark’s Avenue between Kingston and Albany Avenues was partially pedestrianized with a midblock park.

The park originated from a visit in 1966 by Senator Robert F. Kennedy and the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation—the country’s first Community Development Corporation which sought to reverse the decline of the neighborhood with new parks.

The midblock interruption was designed by renowned architects I.M. Pei and M. Paul Friedberg with input from residents. The project was dedicated in 1969 with a ceremony attended by RFK’s widow Ethel.

Other unique features on this block are its light fixtures and parking scheme, which discourages large vehicles and forces very slow driving. Prospect Place runs parallel to this mini-park. It has traffic-calming concrete bollards and a bump in the middle of its block, designed by the same team as the St. Mark’s superblock.

A block to the north of this miniature park is Revere Place, a rare midblock street in this rectangular grid. It is located within the Crown Heights north historical district, so all the buildings on it are safe from demolition. At 11 Revere Place, Richard Wright wrote the novella The Man Who Lived Underground, and the book 12 Million Black Voices.

To the east of Albany Avenue, the architecture becomes less historic. The MTA Bergen Street Sign Shop doesn’t have any trains or buses. This is where the agency’s machinists, electricians, and ironworkers are based. The site has a long transit history, having previously served as a trolley depot.

A portion of the property contained the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, which relocated to Long Island in 1911. In 1906, its most famous resident was Ota Benga, a former slave from Congo who was used for museum and zoo exhibits. To avoid publicity, he relocated to Virginia in the last years of his life.

Across the street from the sign shop is another interruption in St. Marks Avenue, resulting from NYCHA’s Albany houses, a set of nine high-rises built in the early 1950s. As with many public housing superblocks across the city, there is enough room between the towers to allow for the street to be restored, if needed

Before the low-income projects were built, this site was a Catholic orphanage that was built in 1868, when this was an outskirt of the city. In those days such asylums had good intentions but poor living and working conditions. On December 18, 1884, a fire tore through the St. John’s Orphan Asylum for Boys, with accounts of pre- 9/11 horror matched only by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and General Slocum. Reports included the burned body of a priest shielding the body of a boy. The death toll counted 21 children and five adults, who were buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in East Flatbush. The asylum is not related to St. John’s University, which had its first campus a mile away in Bed-Stuy. They both relocated to Queens after World War Two- St. John’s Home was reestablished in Far Rockaway in 1948, and the university’s Hillcrest campus opened in 1954. There are no monuments or plaques for the fire tragedy on the grounds of Albany Houses.

Across Troy Avenue from these high-rises, the orphanage’s name is preserved with St John’s Park. It was built in tandem with Albany Houses, to provide recreational space for its residents. Unlike Brower Park, this green space is entirely flat, dedicated to sports fields, along with a playground and basketball courts. A walkway bisecting the park preserves the route of St. Marks Avenue that was demapped here when the park was built.

St. John’s Recreation Center is a simple brick structure without any architectural embellishments. Fortunately, there is one creative feature on its back wall, a mural by the CityArts organization and artist Duda Penteado completed in 2009. The Rec Center contains classrooms, a gym, and an indoor pool.

The super block containing St. John’s Park had dozens of walk-ups and small homes that were condemned by Robert Moses for the NYCHA project and park. At the time the city’s master builder had the power to build schools, parks, and roads at the same time within a single project.

There is one holdout building within St. John’s Park that survived Moses’ eraser, the former Rescue 2 company firehouse, which was vacated in 2019. When land of the park was designated, this firehouse was deemed important enough to survive condemnation. It dates to 1893, when Brooklyn was an independent city with its own fire department. The unused building still belongs to FDNY and I am not aware of its next purpose now that Rescue 2 is at its new postmodern home at 1815 Sterling Place, a mile to the east.

How large is Crown Heights? Depends who you ask, but on some maps, it is everything between Atlantic Avenue to the north and Empire Boulevard to the south; Washington Avenue to the west, and Howard Avenue to the east. But there is an old neighborhood within it that features prominently in Brooklyn’s Black history. I’ve written in 2017 about Weeksville, and perhaps the blocks to the east of St. John’s Park can be designated as such. P.S. 243K across from the park is co-named the Weeksville School, but this modernist building isn’t worthy of much attention. On the same block is an older school designed by CBJ Snyder, the abandoned P.S. 83, with its beaux arts keystones and pediments.

The site has been used for schools since 1839 when it was a public Colored School. It made history in 1893 as the city’s first racially integrated school. Like the colored asylum a block to the west, this school was also part of the historic Weeksville community. The city gave up this building in the 1960s and it has been vacant since. There are plans to develop it into an apartment building.

Precedents for this old-school to residential conversion include P.S. 135 in Turtle Bay, now the Beekman Regent condos, P.S. 157 in Harlem, rebranded as the PS157 Lofts, and the former P.S. 186 in Hamilton Heights.

Another element of local Black history history can be seen on a plaque at 1605 Dean Street, the low-rise NYCHA Weeksville Gardens apartments. During the construction of these buildings in the early 1970s, archaeologists were on the scene to uncover evidence of its historic namesake community. There are other small parks and housing project superblocks further east, but that’s all for now.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

5/8/22