Once one of New York City’s only two commercial airports (along with North Beach/LaGuardia Airport) Floyd Bennett Field now borders the southern stretch of Flatbush Avenue between Marine Park Golf Course and Jamaica Bay. Though it’s a National Historic Site, it’s little visited these days, except when flea markets are held there, and much of it lies in ruins.

The old seaplane base on West 31st Street is now a heliport; North Beach is now called LaGuardia Airport.

Floyd Bennett Field’s Administration Building is now called the Ryan Vistor Center.

Constructed on the site of Barren Island and additional landfill, Floyd Bennett Field was New York City’s first municipal airport. The airport is located in the southern part of Brooklyn between Flatbush Avenue and Jamaica Bay, and was completed in 1930 ( a smaller airfield, Barren Island Airport, had been there since the mid-1920s) and dedicated by Mayor Jimmy Walker. The airport initially had only two perpendicular runways. The terminal building was topped by an air traffic control tower and featured modern innovations such as underground tunnels extending from the basement to the ramp area. This allowed passengers to comfortably walk from the terminal to their aircraft in any weather. A barber shop, weather room, pilot’s lounge, passenger lounge, and restaurant were also part of the modern terminal (by the nascent airline industry standards).

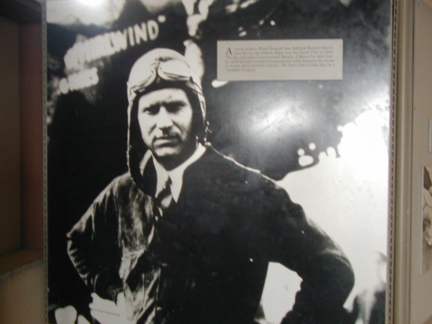

Who’s Floyd? From the deepcreekyachtclub website…

Floyd Bennett, born in Warrensburg, N.Y., had lived in Brooklyn and had been New York’s favorite aviator. He enlisted into the Navy for flight training in 1917. Winning his wings, Bennett first served as a test pilot and later as a Chief Machinists’ Mate aboard the U.S.S. Richmond, in charge of aircraft. It was while aboard the U. S. S. Richmond that Bennett met Admiral Richard E. Byrd. In 1925, he accompanied Byrd on the MacMillan Expedition to the Arctic. On May 9, 1926, Byrd and Bennett took off and made history by being the first men to fly over the North Pole. For this feat, both men were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Plans were being made for a second trip, this time to the South Pole. Bennett did not live to realize the triumph of the South Pole Expedition. In April 1928, while suffering a high fever, he heard of the flight of Irish-German crew of the ‘Bremen’, which was forced down at Greenley Island, Quebec, on an attempted non-stop flight from Europe. Bennett was not acquainted with any of the pilots on board the ‘Bremen’, but they were fellow fliers and explorers in trouble, and despite his fever, he took off immediately from Detroit to try a rescue.

At Murray Bay, he was stricken with influenza, but refused to turn back. Halfway on his journey across Canada, Bennett died of pneumonia. Floyd Bennett was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia. Out of respect for Bennett, Admiral Byrd took a stone from Bennett’s grave and dropped it over the South Pole on the flight that he and Bennett had planned together.

When first built, Floyd Bennett Field’s Administration Building was flanked by eight fireproof hangars, each measuring 120 by 140 feet. Four concrete runways, from 3,200 to 4,200 feet long and from 100 to 150 feet wide, crisscrossed the field. The two towers at the landing zone were equipped with 5,000,000-candle-power floodlights, which supplement the regular beacon boundary, and obstruction lights. Blind landings at the field were facilitated by directional radio beam and a special runway bordered by contact lights.

On this spot, in the rear of the Ryan Center, Howard Hughes took off and landed after completing a round-the-world record flight of 3 days, 19 hours, 17 minutes on July 14, 1938, beating Wiley Post’s old record by more than 4 days. He was met by a crowd of 25,000.

On July 17, 1938, the same month Hughes made his record flight, Douglas Corrigan sought to take off from Floyd Bennett to fly to Ireland, but was denied permission by the Civil Aviation Authority (the governing body at the time) becuase his $299 Curtiss-Robin single engine aircraft was not deemed airworthy. Corrigan then took off for his home in California instead. 28 hours later, Corrigan landed in Dublin, claiming that a faulty compass caused him to fly in the wrong direction. His, er, error caught the public fancy and “Wrong Way” Corrigan received public acclaim upon his return to the USA and a ticker tape parade up Broadway.

A view of the tower from the runway.

Floyd Bennett is not a “dead” airfield. The tower was manned and busy while we were there; and while we were exploring the nearby swamplands, we heard a low roar and sure enough, saw a chunky cargo aircraft rising into the sky through the weeds. Such flights, we’re told, take place about once a week.

This commemorative plaque is hidden at the rear of the tower, evading all but the most persistent seekers.

The plaque dates to the late 1930s when Floyd Bennett was much busier than it is now.

In the above pic you can also see the newly expanded bike path, part of the Gateway National Recreation Area’s emphasis on cleaning up and rehabilitating parkland areas. In Brooklyn alone, plenty of bike paths I remember from my 35 years there as being weedy and full of trash and broken glass have been repaved and maintained. Why’d I ever leave?

Floyd Bennett is now used as home base for the NYPD air squad, the Emergency Services Unit Brooklyn squad, and the field is used to train MTA bus drivers and is also a Department of Sanitation training area. Its once busy runways are mostly desolate.

A November 2004 visit with explorer Andrew N. saw us visit some abandoned warehouses and hangars at the east end of Floyd Bennett Field…

The ruins in the interior of this Public Works building show that Floyd Bennett Field may at one time have had both a church, from which the old pews may have come, and a theatre or auditorium, explaining the very old attached seats.

Andrew felt like a stroll, so he went on the second-floor girders beneath the roof. There was no floor in spots here.

On to abandoned Public Works building #2…

A Sanitation Department training area, empty runways, and a surprisingly good view of distant Manhattan can be seen from the hundreds of Public Works building windows.

We visited another abandoned Public Works building. Probably, little activity in these buildings for the past ten years at least.

Time to visit one of the former hangars. We saw no airplanes, new or old, during this visit, though an adjacent field contains a helicopter port and the occasional cargo plane takes off from here, as explained above.

Forgotten Fan Chris Ciesla of Bagley, Iowa identifies the tool above as a hay rake. [This] particular one looks like a current production item and not just some cast-off junk. The way it works it that when you mow hay, the mower drops the hay on the ground. You let it cure a few days and the you run the hay rake over it to pile it up in neat rows for the baler to pick-up and put in bales.

“I suspect that the city cuts its own hay off of grassy fields to feed to the NYPD Mounted Police horses.”

Our last stop was what appeared to be a former Marine recruitment office.

ForgottenFan Paul Newman: The building on the website you ID as a Marine Corp recruiting station was actually a Marine Corps Barracks for “Weekend Warriors”. There was a permanent Marine Corps Detachment there. Floyd Bennett Field, from the end of WWII to sometime around 1970 was a US Navy Reserve training center. There were a large amount of “Station Keepers” whose job it was train members of the Navy Reserve and also maintain the aircraft at the station. Floyd Bennett was also used as a terminal by members of the congress and high ranking officers having to visit the NYC area. It was also the site used by John Glenn on July 16, 1957 to set a transcontinental speed record flying from NAS Los Alamitos, CA to Floyd Bennett Field in 3 hours and 23 minutes. The Blue Angels also staged air shows from Floyd Bennett when appearing in New York. There was also a Coast Guard Base at the field with helicopter and seaplanes both used for search and rescue. Where the administration building and the hangars along Flatbush Avenue are, the Air Force also had a reserve program whose mission was much the same as the Navy and the Marines.

Marine Park

To the south and west of Floyd Bennett Field can be found vast (about 1800 acres) Marine Park. Until recently, it was mostly ‘wilderness’, but trails are now maintained and residents of Gerritsen Beach and the surrounding neighborhood, also called Marine Park, can revel on a shoreline natire milieu.

The park surrounds Gerritsen Creek, an arm of Jamaica Bay. Gerritsen Creek was a freshwater stream that once extended about twice as far inland, all the way up to Kings Highway, as it does today.. Around 1920 the creek north of Avenue U was converted into an underground stream directed to it’s current release site by a huge pipe or storm drain. Yet it continues to supply the salt marsh with fresh water, which helps the marsh support a wide range of organisms. Broad expanses of fertile salt marsh, meadows adorned with wildflowers, sandy dunes held in place by beach plants, and jungle-like thickets of shrubs and vines dominate the western lands of Gerritsen Beach’s landscape (Marine Park). Myrtle warblers, grasshopper sparrows, cotton-tailed rabbits, ring-necked pheasants, owls, opossums, cranes, horseshoe crabs, and oyster toad fish are a small sampling of the animals that inhabit these plant communities and live in or around Gerritsen Creek.

The creek was probably a favorite hunting and fishing spot for Indians living in the nearby Keshawchqueren village. Archaeological excavations in Marine Park have revealed food preparation pits dating from 800 to 1400 A.D. and containing deer and turtle bones, oyster shells, and sturgeon scales. The first Europeans to settle here were the Dutch, who found the salt marshes and coastal plain of southern Brooklyn reminiscent of Holland’s landscape. Their diet consisted of farm produce, livestock, game, and harvests of oysters and clams.

At the turn of the century developers began making elaborate plans to turn Jamaica Bay into a port, dredging Rockaway channel to allow large ships to enter the proposed harbor. Speculators anticipated a real estate boom and bought land along the Jamaica Bay waterfront. Fearing that the relatively pristine marshland around Gerritsen Creek would be destroyed, Frederick B. Pratt and Alfred T. White offered the city 150 acres in the area for use as a park in 1917.

After a seven-year delay the City accepted the offer. The prospect of a new park inspired developers to erect new homes in the area, although park improvements were slow to follow. Fill deposited in the marshlands in the 1930s and new land purchases increased the park’s area to 1822 acres by 1937. That year the Board of Aldermen named the site “Brooklyn Marine Park.”

Gerritsen Creek, and nearby Gerritsen Avenue, take their names from the Dutch Gerritsen family, who owned property where Marine Park is now as early as the mid-17th century. The family had a milling operation that ran continuously from two buildings in the Marine Park area until 1934, when the second of the two mill buildings burned down…perhaps by arson.

The mills had wooden machinery, leather beltings and large revolving millstones. It was on the edge of the basin into which poured the sea when the rising tide opened the flood gates of the dam that crossed the narrowest part of the creek (originally Storm Kill, later called Gerritsen’s Creek). When the water reached the top of the dam, the gates closed with a full pond behind them. A gate in the sluiceway in the back of the mill could be raised by hand by means of a ratchet wheel, and thus allow the water to flow over the mill wheel as needed.

The second of the two mill buildings is shown here; it was most likely built around 1755. This mill was in continuous operation by the Gerritsens until the late 1890s; William S. Herriman, the last person to run the mill, sold the property in 1899 to the Whitney family, who used the acreage as a training area for his stable of race horses.

These days the old mill is represented only by a group of wooden pilings in the creek.

Over the past sixty years, portions of Marine Park have been improved with recreational facilities, while other areas have been conserved to protect wildlife and plant life. In 1939 the Pratt-White athletic field, north of Avenue U, was dedicated in tribute to the two fathers of Marine Park. A 210-acre golf course opened in 1963. New ballfields, on the west side of Gerritsen Avenue, were opened in 1979 and named for baseball lover and police officer Rocco Torre in 1997. Nature trails established along Gerritsen Creek, on the west side of Burnett Street, in 1984-85, invite parkgoers to observe a wealth of flora and fauna. Ongoing improvements at the end of the 20th century include the reconstruction of basketball, tennis, and bocce courts; of baseball fields; and of Lenape Playground at Avenue U. A new nature center opened in 2000.

In 1974, the Gateway National Recreation Area, a national park, was established. Over 13,000 acres of city parkland in Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island were transferred to the National Park Service in this major reassignment of jurisdiction over the city’s parks, beaches, and wetlands. 1,024 acres of the new Gateway National Park came from Marine Park.

Sources:

Old Dutch Houses of Brooklyn, Maud Esther Dilliard, Richard R. Smith 1945; out of print

The Neighborhoods of Brooklyn, Kenneth T. Jackson, ed.; Yale University Press 1998

4/5/03; updated 2004, 2012