“YOU CAN SEE ALL THE STARS as you walk down Hollywood Boulevard,” says Ray Davies, and they’re there, right in the sidewalk for all to see. But the ghosts wander the Bowery as well. There’s Big Mose, the 8-foot tall fireman who, in Ned Buntline‘s 1840s dime novels, vanquished entire gangs using uprooted trees and could swim the Hudson in two strokes; the myriad gangs who both fought and assisted Tammany Hall in its battles with the Nativists for control of the city; Stephen Foster, who wound up penniless here in 1864; the estimated 25,000 “Bowery bums” who lived in flophouses, lodging houses, stairwells, doorways and fire escapes in the early years of the 20th Century; the theater owners and actors whose ritzy establishments populated the lane before showbiz moved uptown; the hookers and the hot-corn girls of the 1840s. And there was John McGurk, who opened a saloon, known as the Suicide Hall, in 1897, whose building survived until 2005.

As Luc Sante writes in Low Life, his amazing chronicle of 19th-Century life in New York,

…until fairly recently the Bowery always possessed the greatest number of groggeries, flophouses, clip joints, brothels, fire sales, rigged auctions, pawnbrokers, dime museums, shooting galleries, dime-a-dance establishments, fortune-telling agencies, lottery agencies, thieves’ markets, and tattoo parlors, as well as theaters of the second, third, fifth and tenth rank. It is also a fact that the Bowery is the only major thoroughfare in New York never to have had a single church built upon it.

It was extended on a winding path north to ferries crossing the Harlem River and then on to Boston. It was also extended south, in the early 1800s, to connect with Pearl Street in a section at first called New Bowery and then St. James Place.

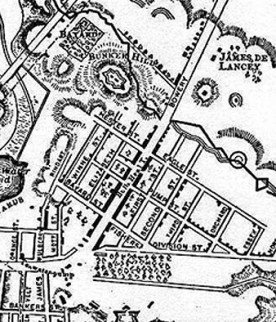

The map at left shows the Bowery proceeding north from what would become Chatham Square in 1782, through the farm of James DeLancey. Yes, New York had a Bunker Hill; it has long since been leveled. In the Bowery roadbed, note the Bulls Head Tavern: it was in business here from about 1750 to 1820. Incarnations of it were elsewhere in the city until 1890.

At extreme left, we see the Collect Pond, once a freshwater body that became stagnant and corrupted after it was used as a garbage dump; it was eventually drained in the canal that became Canal Street; and southeast of that, the Teawater Pump: a freshwater spring the locals used to make their favorite beverage. A resort known as the Teawater Garden arose in the region. By 1829, though, the resort had disappeared, though it lent its name to Pump Street (now known as Canal), which angled nearby.

1782 map from Brooklyn Genealogy.

Let’s see if we can find a few ghosts as we walk up the Bowery from where it starts to where it ends; from one maze of roads to another, though I don’t believe in ghosts and neither should you. If the Bowery doesn’t have ghosts, it doesn’t have a lot of shade either, and hasn’t since 1955: the elevated train, the Third Avenue El, that ran along its entire length since the 1880s was razed that year.

The Bowery begins at Chatham Square, named for the Colonies-sympathizing British Earl of Chatham, William Pitt (of Pittsburgh fame). No less than 9 streets converge here: Worth, Mott, Park Row, Bowery, St. James Place, James Street, Oliver Street, East Broadway (formerly Chatham Street) and odd little Doyers Street, the cart path that twisted past Henry Doyer’s distillery in the early 1800s. Doyers has been called the “bloody angle” from Chinese gang wars that have erupted along its length over the years. An apothecary opened in 1806 at No. 6 Bowery in the Square, Olliffe’s, served area customers until 1982: a run of 176 years.

19th-century Chinese anti-narcotics fighter Lin Ze Xu looks north from Chatham Square.

The Chatham Square area has been settled since about 1660 when Thomas Hall petitioned to form a village in the vicinity of Collect Pond. In the 1670s the area possessed a “wild west” atmosphere as wild horses were rounded up and branded here. Chatham Square, then far north of downtown, would soon become the city’s center for horse auctions.

In 1858, the first Chinese in the area, a tobacconist named Ah Ken, set up shop on Park Row, but the area would not become the Chinatown we know until between 1880 and 1910, when the Chinese population numbered fully 15,000. Today, it is nearly 20 times that number.

The Shearith Israel Cemetery, dating to the mid-1680s, is a remnant of Chatham Square’s earliest days; it is the original burial ground of Spanish Jews of the region. It is a fraction of its original size since New Bowery (St. James Place) was cut through in the mid-1800s.

1934 view of an apothecary opened in 1806 at No. 6 Bowery in the Square, Olliffe’s, which served area customers until 1982: a run of 176 years!

Just east of Chatham Square, we see some overprinted ads on an 1880s brick building. Charles Fletcher’s Castoria can be made out, but there are couple of others; one says “Turkish”, a reference to Turkish Trophies cigarettes, made with Turkish tobacco, as seen in the same scene with the Second Avenue El in 1905. Bottom photo by Edward Watson, courtesy Kenneth Askin. The two are the same ad.

The Baptist Mariner’s Temple, formerly the Oliver Street Church, is a landmarked structure designed by Isaac Lucas and built in 1844.

On Bowery between Bayard and Canal, a McDonalds has adapted itself to the local milieu. Any Forgotten Fans reading Chinese, please let me know what the characters above the door mean…

Forgotten Fan Hudson Cheung says the characters are a transliteration of ‘McDonalds.’

18 Bowery, the southwest corner of Pell Street, now home to Security Mortgage Bankers, is the oldest remaining house on the street. It was built sometime before 1789 for merchant Edward Mooney; it may be Manhattan’s last remaining row house. When it was built the Bowery was on the outskirts of town and the house was in a well-to-do area, but by the 1840s, Mooney was gone and the house was a brothel. The building was restored to its original appearance in 1971.

For many years, the fantastically-detailed Manhattan Bridge colonnade and arch, based upon some of the ones in Paris and Rome, was horribly stained and darkened by decades’ worth of exhaust fumes from pedal-to the metal traffic, and even endangered by Robert Moses, who wanted to tear it down for a double-decked elevated highway.

The arch’s design, by Carrere and Hastings, features Charles Rumsey’s Buffalo Hunt sculpture on the frieze above the arch (not pictured here). The approach was magnificently restored in 2000; the reinvigoration included the installation of new lampposts between the Bowery and the arch.

The bronze-domed Citizen’s Savings Bank building, built in 1924, the first in a procession of Bowery banks, is now a branch of HSBC (Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation), which cannot seem to adapt is signage to any of its buildings, no matter how historic.

5-story arched building on Bowery just north of Hester, formerly Worth’s Museum.

At the vanished National Theater, 104 Bowery, Frank Chanfrau would enthrall audiences of the 1860s with his portrayal of the firefighter Big Mose, and the first stage production of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” played at the National in 1852.

The Bowery, more than any other New York street,makes abrupt stylistic and thematic changes. Between Canal and Hester, the street is an intense nexus of diamond and jewelry stores, second only, perhaps, to W. 47th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues (Diamond and Jewelry Way).

On the southeast corner of Bowery and Hester is the remains of the last Chinese-language movie theater in Chinatown, the Music Palace, though a 4-story mural can still be found on the Hester Street side. Its 1960s façade obscures the original McKim, Mead & White fronts. It closed its doors in 2000.

Hudson Cheung: “The (vertical) characters on the old Music Palace are pronounced as “Chuan-Kung-Chi-Yuan”, which means “Chuan Kung Theater.

“Chuan Kung Theater had only one hall. They used to show 2 different movies in a row. You could watch both of them with one ticket (it was $5 in 1990).

“The theater had a small exit on Hester St., which is now used by a small shop. The awnings reads Daibo Trading Co.; the characters mean “Daibo Ginseng Company”.

Old-school candy store sign, Bowery and Hester.

The Coogan Brothers operated a dry goods and/or furniture store here between Hester and Grand; 1888 photos show this painted sign in place even then, so it has survived close to 125 years. And yes, there is a connection to Coogan’s Bluff uptown near the old Polo Grounds.

The Bowery’s most magnificent bank, the one named for it, is now no longer a bank building. At 130 Bowery and Grand is Stanford White’s Bowery Bank building, completed in 1895. Bowery Bank had stood in this location since 1834: this was the third building. It was the first Roman Classical style bank building in America. The interior featured marble mosaic floors, yellow marble tellers’ counters, and cast-iron skylights and stairs. Thankfully the building has been saved and is now the Capitale nightclub. The large characters on the exterior are an ad for a kindergarten. Some of the old interior can be seen at the Capitale website.

Kessler’s Hardware, Grand Street; and Grand Hotel, one of the last Bowery flops, which has been renovated into a lodging for Chinese immigrants.

At Bowery just north of Broome, you see a painted ad for what you might think is a dying industry…traditional cash registers and scales, with the little levers and dials, but National still seems to be going strong.

Between Grand and Spring, the Bowery changes character again and becomes New York City’s capital of wholesale lighting fixtures, with old-fashioned and modern window displays.

The Crystal, just south of Delancey; former single room occupancy hotel, now offices and apartments.

The old Germania Bank building, 190 Bowery at Spring Street, has become a mecca for street artists; its exterior is faded, rusted, corroded glory, with Beaux-Arts hints of another age splattered with the artistic statements of a new one. Famed NYC photographer Jay Maisel and his family have been the sole occupants since 1966.

As historian Herbert Asbury recounts in his 1930s book All Around the Town, in 1824 a carpenter named Lozier, abetted by a butcher named Uncle John DeVoe, perpetrated an elaborate hoax in which they proposed to saw off the lower end of Manhattan. After a meeting with Mayor Stephan Allen, it was decided that Manhattan had become way too heavy, with the big buildings and all, so for safety’s sake, it had to be separated lest the whole island sink!

Lozier appeared at City Hall with a huge ledger on which he inscribed the names of the out-of-work laborers who applied to the task; engaged scores of carpenters and contractors to furnish lumber to build barracks for the workmen; hired butchers for the purposes of preparing cattle, hogs and fowl to feed the workmen; and, of course, drew up plans for 100-foot saws and other mechanical appliances to effect the geat saw-off, for which blacksmiths and mechanics feverishly set to work designing. Lozier…

“instructed all who were to have a hand in the great work to report at the Bowery and Spring Street, where they would be met by a fife and drum corps which he had thoughtfully engaged.”

About 500-1000 persons turned up on a July day at the corner. Of course, Lozier and Uncle John never showed.

On Kenmare just west of the Bowery is another odd painted ad palimpsest, like the one we saw at Chatham Square. This one is actually two ads for Zuccaro Real Estate, Bendix Home Laundry (a brand of appliances; I’ve seen the Bendix name associated with ads for All elsewhere around town). J. Eis and Son is listed at the bottom.

Forgotten Fan Joseph Ditta says he has found J. Eis and son on a vaccum cleaner ad in the April 16, 1948 New York Times. So, Eis probably had something to do with the Bendix ad as well.

When we get north of Spring we encounter the Bowery’s biggest business…wholesale kitchen equipment, chef’s supplies, ovens, and even kitchen furniture. Bari Restaurant Equipment is likely the biggest name here. The upper Bowery has provided restaurateurs and chefs with professional wares since the early 1930s.

The Sunshine Hotel, 241 Bowery, is said to be one of the Bowery’s last old-line Skid Row era flophouses. As decribed by Debra Lynn Blumberg inThe Villager, the Sunshine opened in 1922; at present 55 men live in small rooms with a bed and a locker, and the use of a communal bathroom.

The Bari family, who owns the Sunshine as well as many of the kitchen supply stores on this stretch of the Bowery, is no longer admitting new residents to the boarding house and would like to buy out the remainder. However the Baris have no intention of evicting any of the residents.

NPR Radio describes the Sunshine thusly:

“Rows of wooden cubicles. Rooms smaller than prison cells. A bed. A locker. A bare bulb and a chicken wire ceiling. Starting at $4.50 a night, Bowery flophouses are the cheapest form of housing available. It’s a lifestyle that many might assume disappeared decades ago. But six Bowery flophouses still remain, including the Sunshine Hotel — opened in 1922 and virtually unchanged since. From an architect who abandoned his family, to a 425 pound man eating himself into seclusion, the backgrounds of the men in the Sunshine run the gamut.”

More on the Sunshine and other Bowery flops:

Flophouse: Life on the Bowery, David Isay, Stacy Abramson, Harvey Wang, Random House 2000

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

The Sunshine Hotel, audio CD of interviews with Sunshine residents, David Isay, Stacy Abramson, Sound Portraits 1999

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

[2012: the sign came down in 2011 when the Bowery Diner was opened in the Sunshine’s building, though the upstairs cubicles remain.]

The Bowery Mission, 227 Bowery near Stanton, has offered clothing, showers, hot meals and medical attention to the neighborhood’s homeless since 1879. The organization also offers Bible classes, computer classes and job training. The Mission always can use volunteers and donations.

Globe Slicers, ‘since 1947’, and probably doesn’t look much different from when it opened.

Before walking the Bowery’s northern stretch, and meeting McGurk for the last time, take a slight detour along the first northbound street to the west, Elizabeth, and walk north to where it ends at Bleecker. Manhattan’s street grid doesn’t offer many vistas like this, where streets end and you can look down to the facing houses and doorways at the end of the street. A faded facade just to the right of Quartino on Bleecker grabs our attention…

Counterculture/antiwar group the Yippies, led by Abbie Hoffman (1936-1989), moved to #9 Bleecker in 1973 after a stint at Union Square. When the building was sold in 2000 the group faced eviction, a partnership was formed allowing the group to stay on. Plans call for the building to become a “Yippie museum” and an advocacy center to fight transmission of AIDS.

Art: #7 and #9 Bleecker Street. LEFT: 2005; RIGHT: 1885

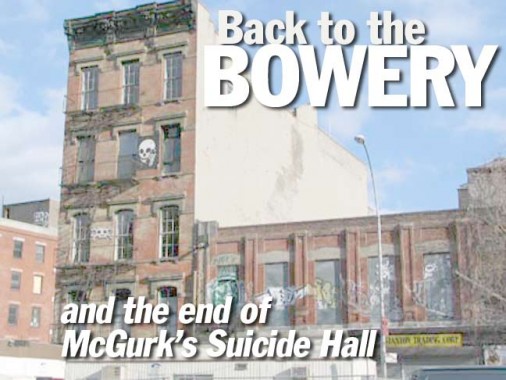

295 Bowery, above Houston: McGurk’s Suicide Hall. The thin. 5-story building with the skull. “The Mama Leone’s of dives”, as Luc Sante puts it, displayed one of the first neon advertising signs in NYC, but that was its only concession to modernity. It was opened in this building by Irish immigrant John McGurk in 1895: his previous drinking establishment had been the Mug, further down the Bowery, where the waiters carried knockout drops. Just in case.

McGurk took similar precautions at his new place. According to Luc Sante, the waiters were armed with chloral hydrate. Prostitutes looking for johns frequented McGurk’s and engaged in a practice that gave McGurk’s its nickname: a suicide craze. There were six in 1899 alone, with the implement of choice being containers of carbolic acid. Most of the women who killed themselves were teenagers between 16 and 18. Waiters came to recognize persons who might attempt suicide and formed flying wedges to eject the aggrieved parties before the deed could be attempted or completed. Nevertheless, the notoriety got McGurk a good chunk of his business. He was forced out in 1902 and would up in California.

The Hall, and the building next to it, the low-rise Hadley Hall, or Volksgarden, a gathering place for German immigrants when they dominated the Lower East Side in the latter 19th Century, then the Stanton Trading restuarant supply company, soldiered on for over a century after.

Writer/sculptor Kate Millett had an apartment in the building for 38 years, and fought eviction, with other tenants, by the Cooper Square Urban Renewal Area, which proposed to build new buildings containing 700 apartments, of which they promise 175 will be low-income units. The tenants lost, and finally accepted a relocation deal.

Winter view of the Liz Christy Community Garden, Bowery and Houston, is a historic artifact in its own right, since it was among the very first community gardens when it was planted in 1973 by Liz and her group called the Green Guerrillas. The garden was closed for most of 2004, when these photos were taken, but it reopened after the demolition of McGurk’s and the opening of the Avalon high rise apartments.

There is not a spare blank public area downtown that is not covered with graffiti or street art. A couple of years ago, all NYC pedestrian stoplights that read WALK or DONT WALK were replaced with The Hand and The Man, for people who don’t read English. The Hand is also altered for, um….the Texas Longhorns symbol…yeah, that’s it. Or the Hand can sometimes become The Bird. I finally found out who is putting the pants and dresses on The Man.

It was over 30 years ago (1973) when the late Hilly Kristal opened Country, Bluegrass and Blues and Other Music for Uplifting Gourmandizers on the ground floor of the Palace Hotel flop at 315 Bowery, across from Bleecker.

On the CBGB website, Kristal recounts the early years…

“Having a rock club on the Bowery, under a flop house (believe it or not), does have some advantages. (1) The rent is (was) reasonable (2) Most of our neighbors dressed worse than, or more weird than our rock and rollers (3) The surrounding buildings were mostly industrial and the people who did live close by, didn’t seem to care too much about having a little rock and roll sound seeping into their lives. The disadvantages: within a two-block radius there were six flophouses holding about two thousand men, mostly derelicts. I would say most of them were either alcoholics, drug addicts, physically impaired or mentally unstable. Some of the men were veterans from the Vietnam war on government disability, and others were just lost in life or down on their luck. The streets were strewn with bodies of alcoholic derelicts sleeping it off after two or three drinks of adulterated wine reinforced with sugar. There were lots off muggers hanging around on the Bowery preying on the old or incapacitated men. When people were let out of jail or institutions they were very often housed in one of these flophouses by the city, so we had to deal with these crazies trying to come into the club.

Mostly, knives were the weapon of choice. By the time things improved around here, I had collected over three dozen knives and other assorted weapons. The muggers – or “jack rollers”- as they were called on the Bowery, were not as dangerous to ordinary people as they seemed. They were used to picking on the old men or others who were completely out of it like three sheets to the wind.

The Bowery was, to repeat, a drab ugly and unsavory place. But it was good enough for rock and rollers. The people who frequented CBGB didn’t seem to mind staggering drunks and stepping over a few bodies.”

The bands that made up the soundtrack to my college years and afterward, The Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, Television, Patti Smith, the Shirts, and so many others, got some of their first NYC stage time here. The first band I saw at CBGB? Certain General.

CBGB closed with a final concert by Patti Smith on 10/15/2006.

Joey Ramone was honored with a section of East 2nd Street between the Bowery and 2nd Avenue in 2003. Jeffrey Hyman was from Forest Hills, Queens, but he made his name here.

In 1976: Lenny Kaye, Patti Smith; Chris Stein, Debbie Harry. Images from “This Ain’t No Disco: The Story of CBGB” by Roman Kozak (Faber & Faber, 1988)

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

The Amato Opera, founded in 1948 by Tony and Sally Amato, was a testing ground for young performers and also presents lesser-known operas by major composers. The Amato is situated in what many experts believe is the world’s smallest opera house…right next to CBGB.

Amato Opera closed after its last performance of The Marriage of Figaro on May 31, 2009, after Anthony Amato retired.

One of the Bowery’s only cast-iron front buildings, #330 at Bond Street, was built in 1874 as the Atlantic Bank Building. The Bouwerie Lane Theatre moved in in 1963 and was joined by the Jean Cocteau Repertory Theater in 1974.

The building was purchased by Adam Gordon in 2007 for conversion into a private mansion with a climbing wall, and the Bowery street front used for retail. wikipedia

Blood and fire. The expressions “on the wagon” and “off the wagon” had their origins on the Bowery where Evangeline Booth (whose father founded the Salvation Army), used to send a horse-drawn wagon onto the throroughfare to pick up drunks and bring them to an Army facility where they could dry out and hopefully put their lives together.

I was attracted to the charming terra cotta “SA” on the exterior. It looks as if it was made yesterday.

It was 25 degrees the day I did the Bowery walk and the day was getting late. Time to think about going inside and warming up. But not before a last look at the Bowery before it gives birth to Third and Fourth Avenues at Cooper Square, where the Empire State, King of All Buildings, makes its presence known over a street that has kept so much of NYC’s past…but loses a little more every year.

We’re not on the Bowery any more, but its symbolic end can be said to come at Cooper Union, where, in 1859, industrialist Peter Cooper built this brownstone Italianate building that employed rolled iron beams, fabricated by Cooper’s foundry, and was among the first buildings that included an elevator (the first was the nearby Haughwout Building at Broadway and Broome Street). Cooper originally offered liberal-arts education here for free!

In February 1860 Abraham Lincoln gave a speech at Cooper Union on why slavery should not be permitted to expand further into US territories. It’s widely held that this successful speech propelled him to the Republican Party’s nomination for President.

Sources:

Low-Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, Luc Sante, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003 reprint. Indispensable!

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

All Around the Town, Herbert Asbury, Thunder’s Mouth, 2003 reprint.

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

New York City Landmarks, Andrew S. Dolkart, Matthew Postal, John Wiley 2004

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

New York Songlines (Bowery), Jim Naureckas

“Another Bite Out of the Bowery,” Dylan Foley, NYPress, January 4, 2005

Village Voice inspects the end of the Bowery, March 3, 2005

This page was photographed on January 21, 2005 and written February 3-5, 2005.